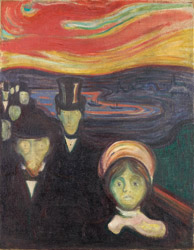

I saw all the people behind their masks—smiling, phlegmatic—composed faces—I saw through them and there was suffering—all of them—pale corpses—who without rest ran around—along a twisted road—at the end of which was the grave.

—Edvard Munch, c. 1916

Although written many years after he painted them, this evocative description suggests the emotionally fraught state of the figures in images such as Anxiety and The Scream, which are among the most powerful and iconic works Munch created. With their jarring use of perspective, these pictures recall the Impressionist cityscapes Munch made of Paris two years earlier. But here, he reimagined and transformed those brightly colored daytime streets into a nightmare of staring faces, darkened avenues, and isolated Norwegian settings. As he turned away from his Impressionist experiments and toward a technique and subject matter all his own, Munch pursued an interest in anxiety and alienation that stretched back to early pictures. He also responded to the example of artists such as James Ensor, whose use of carnivalesque masks would have presented him with an ideal means of conveying his distaste for false bourgeois morality. The raw, almost mystical paintings of Gauguin and van Gogh, meanwhile, displayed the disorienting spaces, mysterious figures, and glaring, acidic colors that Munch incorporated into his own work as he sought to raise the sense of tension to a fever pitch.

Edvard Munch. Anxiety, 1894. Munch Museum, Oslo, MMM 515.© 2008 The Munch Museum / The Munch-Ellingsen Group / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.