Ansel Easton Adams

American, 1902–1984

Ansel Adams was among the handful of younger photographers embraced by Alfred Stieglitz in the 1930s, and he would go on to gain acclaim for his heroic western landscapes and precise technique. Along with several other West Coast photographers, Adams founded Group f/64 to advocate for sharp overall focus and contact printing as the best means of expressing the camera’s full potential. He also taught photography workshops and published several technical manuals. An ardent naturalist, he served on the board of directors of the Sierra Club for many years and used his work to promote environmentalist causes.

Adams made a pilgrimage to meet Stieglitz at An American Place in April 1933. Although Stieglitz initially rebuffed Adams, at their second meeting he carefully viewed—and viewed again—the prints Adams had brought for his inspection. Adams later recalled Stieglitz saying, “These are some of the finest photographs I have ever seen. I want to continue to see your work. You are always welcome here.”[1] Thereafter Adams kept up a close friendship with Stieglitz through letters and regular visits to New York.

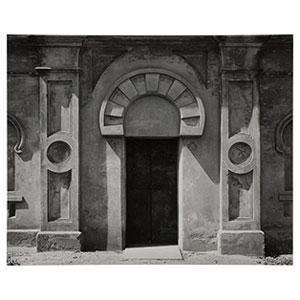

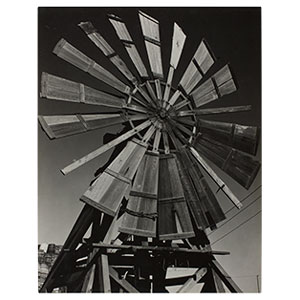

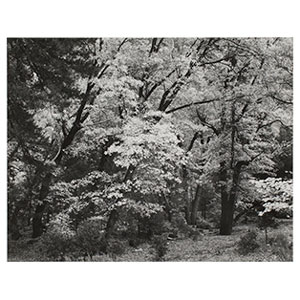

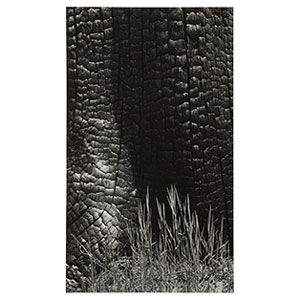

Stieglitz granted Adams a one-man exhibition at An American Place in 1936, and although it was not Adams’s first show in New York, it was certainly his most important. He spent months painstakingly printing forty-five negatives made over the previous five years, a group that encompassed portraits; close-ups of subjects from nature such as trees, pinecones, and leaves, as well as man-made objects; architectural images; and landscapes. Stieglitz acquired six of the works from the 1936 show, two of which are in the Art Institute’s collection. In the exhibition pamphlet, Adams explained his approach to photography:

Perception, visualization, and execution are rigorously interrelated; each in itself has little meaning. A competent technique is quite essential in photography, and an adequate and precise apparatus also, but without the elements of imaginative vision and taste the most perfect technical photograph is a vacuous shell.[2]

Adams visited the show toward the end of its run and was quite pleased with both the presentation and the resulting sales. He wrote to Stieglitz in December of that year, “I wonder if you can ever know what your showing of my work has done for my whole direction in life?”[3]

[1] Quoted in Weston Naef, The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1978), p. 238.

[2] An American Place, Ansel Adams: Exhibition of Photographs (An American Place, 1936).

[3] Quoted in Andrea Gray, Ansel Adams: An American Place, 1936 (Center for Creative Photography, 1982), p. 34.