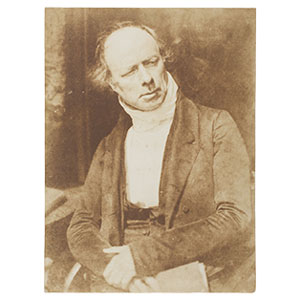

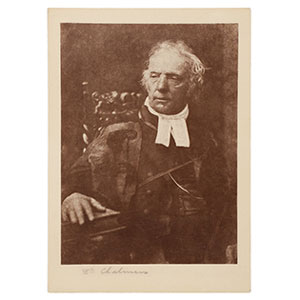

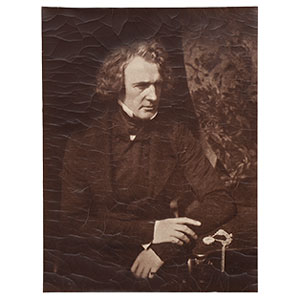

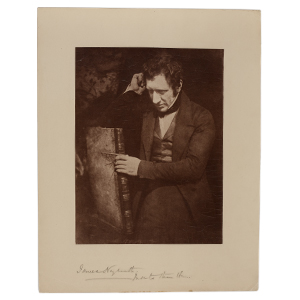

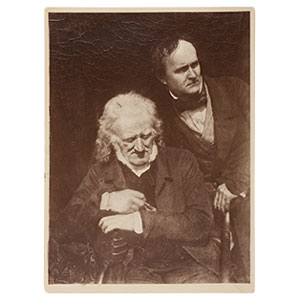

David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson

Scottish, 1802–1870 and Scottish, 1821–1848

One of the most important collaborations in the history of photography began when the Scottish artist David Octavius Hill, hoping to make a grand commemorative painting, enlisted Robert Adamson—who possessed technical knowledge about the then-nascent art of photography—to help with portrait studies. The duo worked together for only five years, from 1843 to 1847, but they were prolific, producing more than fifteen hundred portraits, including images of local gentry and the men and women of the fishing village of Newhaven. Their photographs—salt prints made from paper negatives—were admired for their artistic composition, following a fashion for masses of form over vulgar or boring detail, and were likened in their day to the style of Rembrandt.

As did many in his circle, Alfred Stieglitz considered Hill one of the few nineteenth-century photographers working in a truly artistic mode (Adamson was overlooked at the time but has since come to be recognized as a crucial partner); in his writings Stieglitz regularly referred to Hill as “the father of pictorial photography.”[1] He included Hill and Adamson’s images in Camera Work on three separate occasions—in 1905, 1909, and 1912. He also exhibited their photographs at the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, alongside work by Frederick Evans and James Craig Annan, in 1906, the only time he showed nineteenth-century photography in his gallery, which would become known for promoting the avant-garde. And when Stieglitz mounted the comprehensive International Exhibition of Pictorial Photography at the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, in 1910, the work of Hill and Adamson—with forty prints on view—was better represented than that of any living photographer.

The photographer and printer J. Craig Annan was the most energetic champion of Hill and Adamson’s body of work. After gaining access to their archive through family connections, he made original prints available for exhibition and produced new photogravures and carbon prints from the paper negatives. The carbon prints in Stieglitz’s collection were probably made by Annan or his father, Thomas.

[1] See, for example, Stieglitz’s “Letter to the Members of the Photo-Secession,” Photo-Era 15 (October 1905), reproduced in Richard Whelan, ed. Stieglitz on Photography: His Selected Essays and Notes (Millerton, NY: Aperture, 2000), p. 178.