Early Negative, Later Print

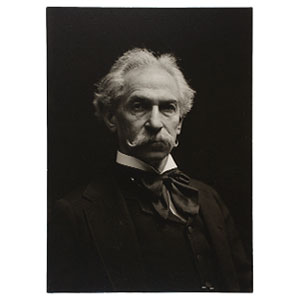

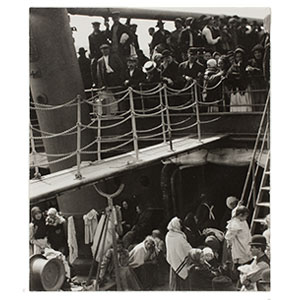

For Alfred Stieglitz, as for the other members of the Photo-Secession, a high-quality photographic print held its own unique value. Although he may have printed various versions of a particular negative, Stieglitz maintained that these were not “duplicates.” As he explained in 1933, “What might seem duplicates . . . are in reality different methods of printing from one and the same negative and as such become significant prints each with its own individuality.”[1]

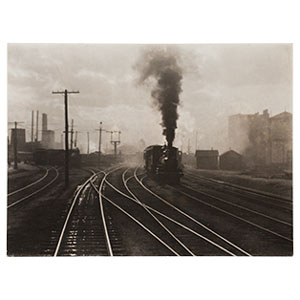

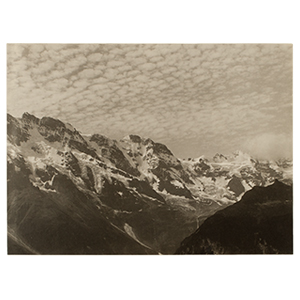

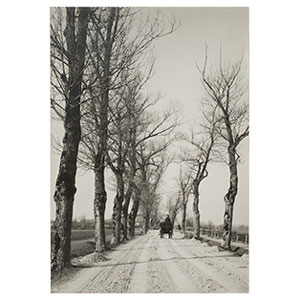

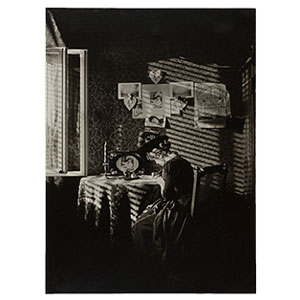

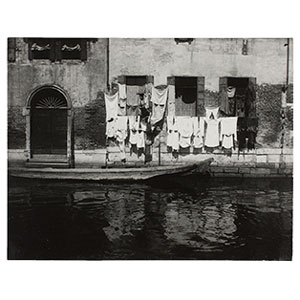

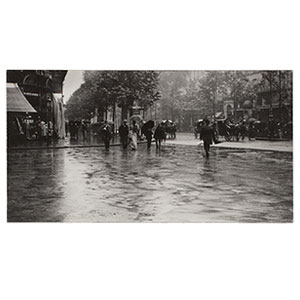

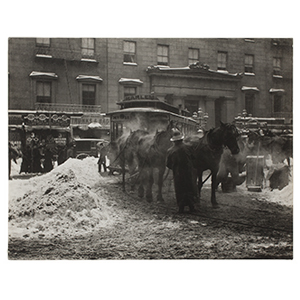

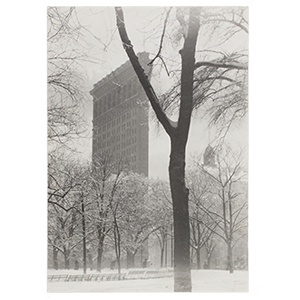

During the early part of his career, Stieglitz printed by enlarging from his negatives and often used only a portion of the image to create the final work. “My experience has taught me that the prints from the direct negatives have but little value as such,” he said at the time.[2] Later in the twentieth century he remade many of his early works as direct-contact (not enlarged), uncropped gelatin silver prints. Glossier, sharper, and cooler in tone than his earlier photogravures or platinum prints, the small silver prints have a much more modern feel.

By reprinting his own work, Stieglitz also reinterpreted it in the context of the modernism he had come to embrace starting in the 1910s. He brought to the images not only newer printing processes but also a refreshed attitude about modern art, photography, and American culture. In 1933 he unearthed a cache of twenty-two old negatives in the attic of his Lake George house and decided to reprint them. “When I saw the new prints from the old negatives,” he wrote the following year, “I was startled to see how intimately related their spirit is to my latest work.”[3] Although his aesthetic had changed—from a painterly, Pictorialist style to one based in the camera’s mechanical qualities—Stieglitz identified a common artistic thread across fifty years of making photographs.

In many cases, the collection features an early photogravure and a later gelatin silver print from the same negative; in other cases, an early negative is represented only by a later print.

[1] Letter from Alfred Stieglitz to Olivia Paine, May 9, 1933, held in the Department of Prints and Drawings, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; cited in Weston Naef, The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1978), p. 9.

[2] Alfred Stieglitz, “The Hand Camera—Its Present Importance,” American Annual of Photography and Photographic Times Almanac for 1897, reprinted in Richard Whelan, ed., Stieglitz on Photography: His Selected Essays and Notes (Aperture, 2000), p. 70.

[3] Brochure for Alfred Stieglitz: Exhibition of Photographs (1884–1934), An American Place, New York, December 11, 1934–January 17, 1935.