Lewis Hine

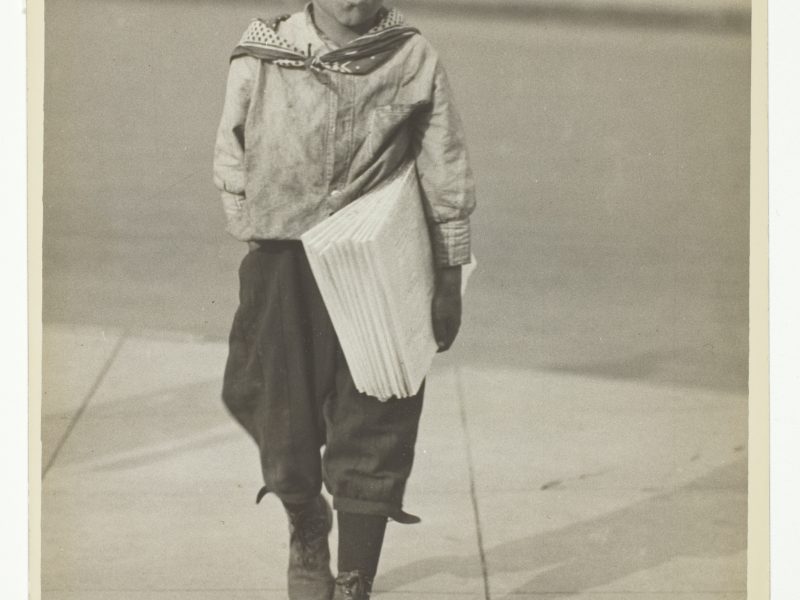

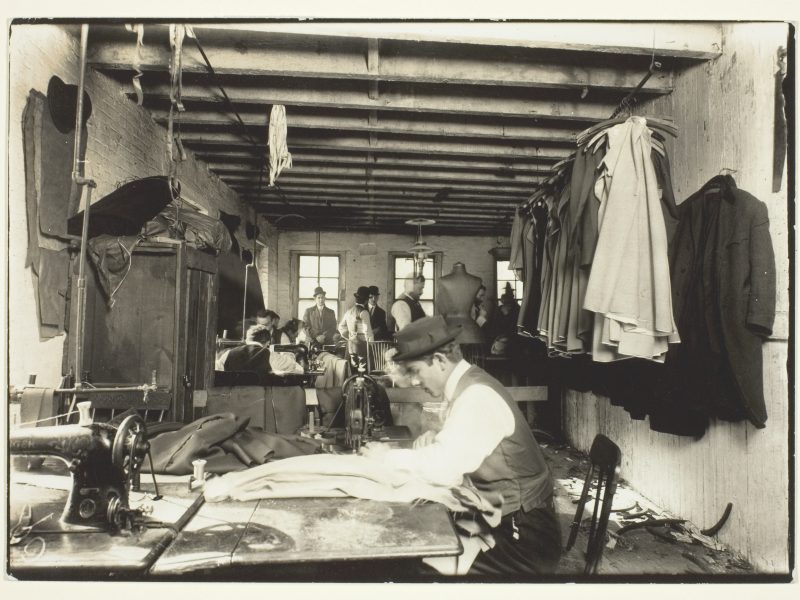

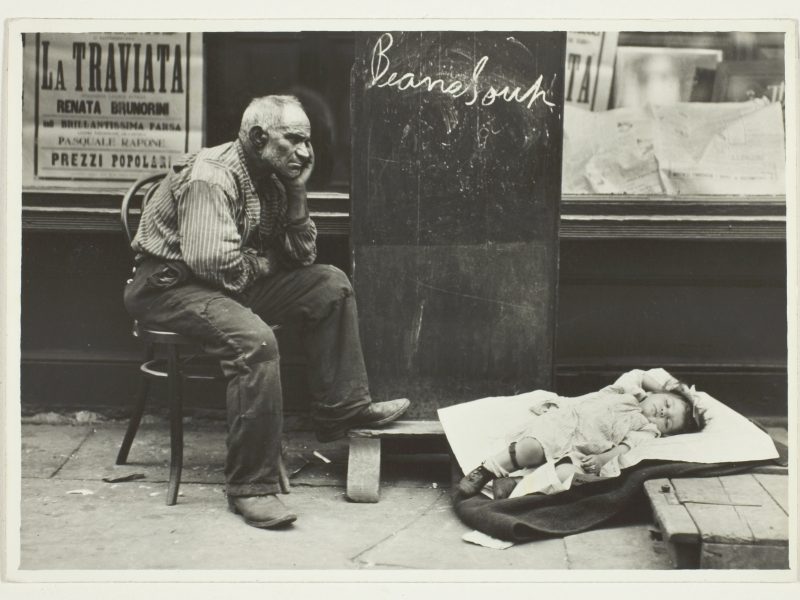

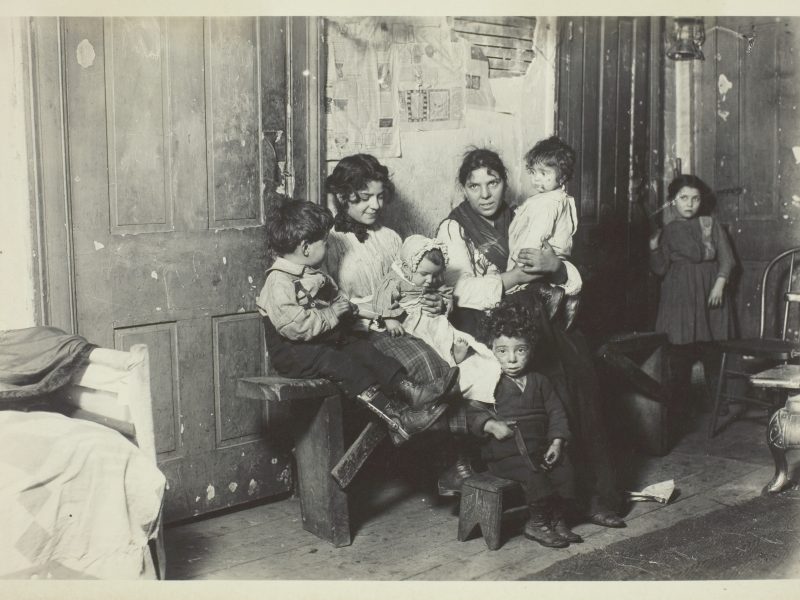

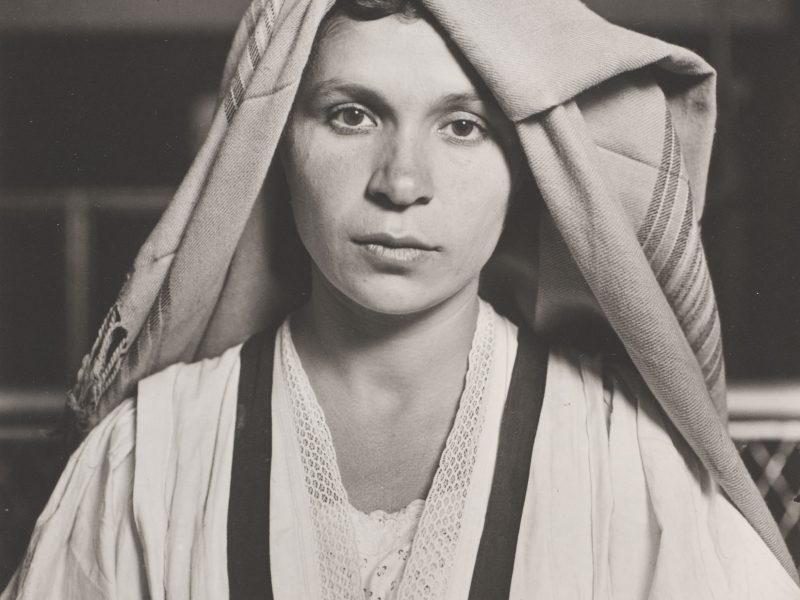

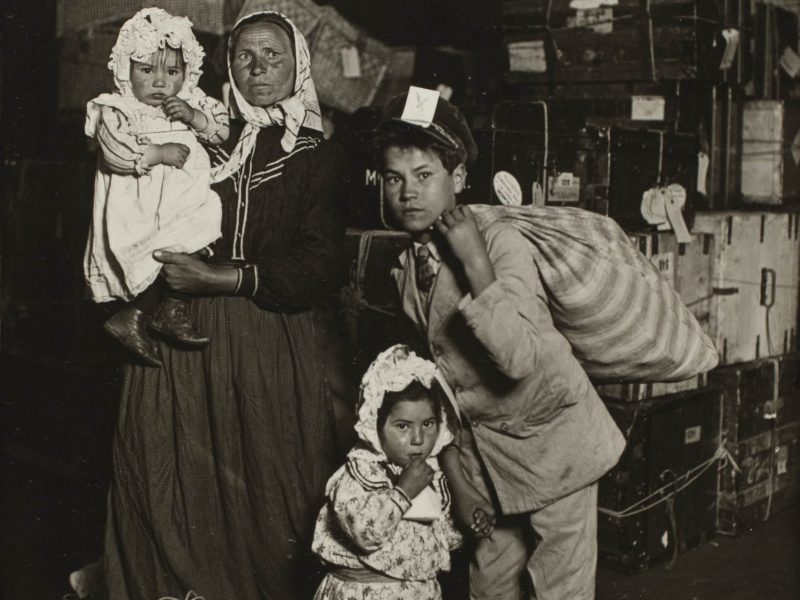

Lewis Hine (American, 1874–1940) was a sociologist who took up the camera to effect social change, particularly around American poverty and child labor. At the turn of the twentieth century he began photographing families passing through Ellis Island during a wave of immigration from poorer countries in Europe. He followed his subjects to their eventual tenement homes, documenting these cramped quarters to highlight the struggles faced by immigrants. From 1906 the National Child Labor Committee employed Hine to photograph and investigate scenes of child workers across the country; these efforts led to humanitarian reforms of American labor laws. He produced some five thousand images of deplorable working and living conditions for underage laborers in coal mines, cotton mills, canneries, and farms, sometimes posing as a fire inspector or postcard salesman. Hine composed his images to elicit sympathy from viewers, who encountered the photographs in exhibitions, periodicals, and lectures. His later photographs expanded to encompass a broader range of labor, depicting honest work in factories and various craft trades as well as the thrilling but dangerous construction of the Empire State Building.

Hugh Edwards classed Hine among the originators of an American realistic tradition in photography, succeeded by Walker Evans and Robert Frank. Asked in 1962 to name a suitable subject for a proposed book series on great photographers, Edwards immediately recommended Hine.[1] Over the course of his tenure, he added more than one hundred Hine photographs to the museum’s holdings, including a small group he donated himself. In 1961 Edwards mounted The Interpretive Photography of Lewis Hine, an exhibition comprising works held by the George Eastman House (where Hine’s negatives had been deposited). Seven years later, he organized a group exhibition—a rarity for him—titled Photography before 1914, which seems to have included eleven Hine photographs. He wrote glowingly of Hine in a label likely written for that exhibition: “It is impossible to find another who had such modest and complete relationship with his material. He stands at the head of that trend, so evident in American photography, which can lift the factual and documentary to the highest plane.”[2]

[1] Edwards to Lewis Kaplan, editor, Universal Photo Books, July 28, 1962, Institutional Archives, Art Institute of Chicago.

[2] Probably Edwards, exh. label for Photography before 1914, 1968, on file in the Photography Department, Art Institute of Chicago.