Robert Frank

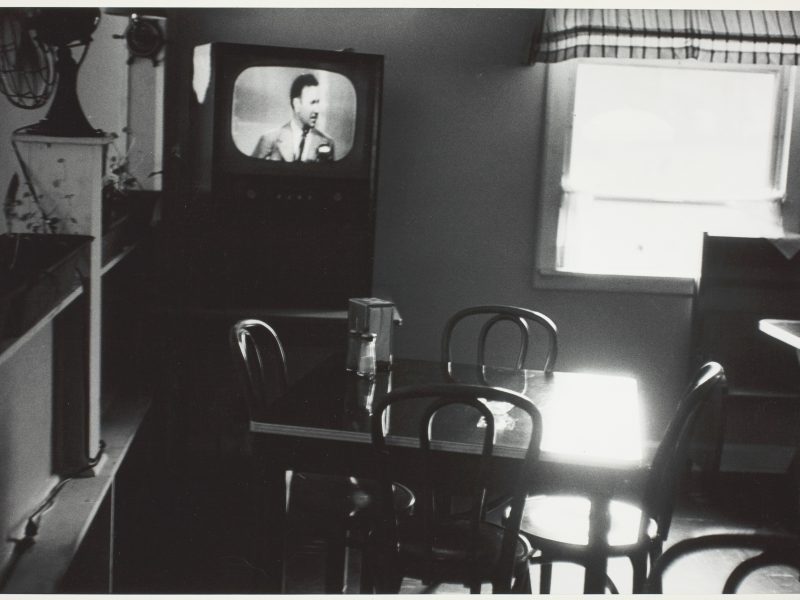

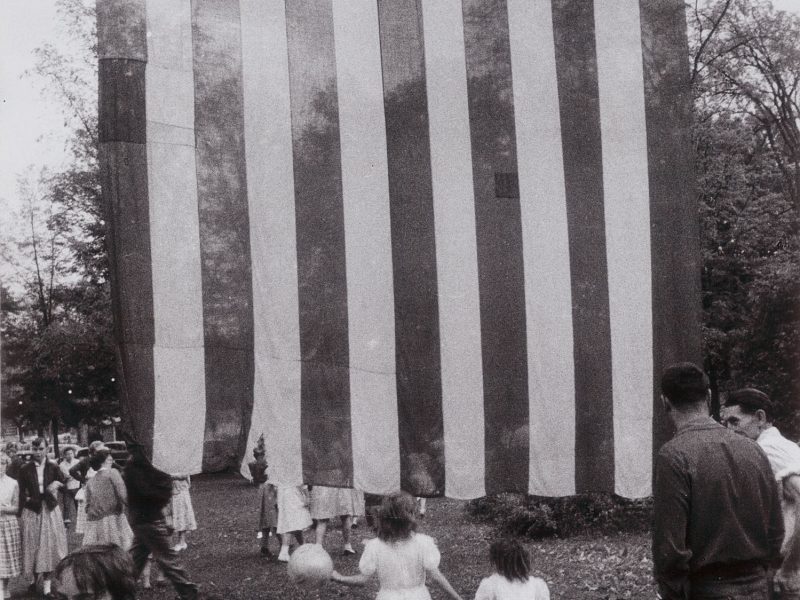

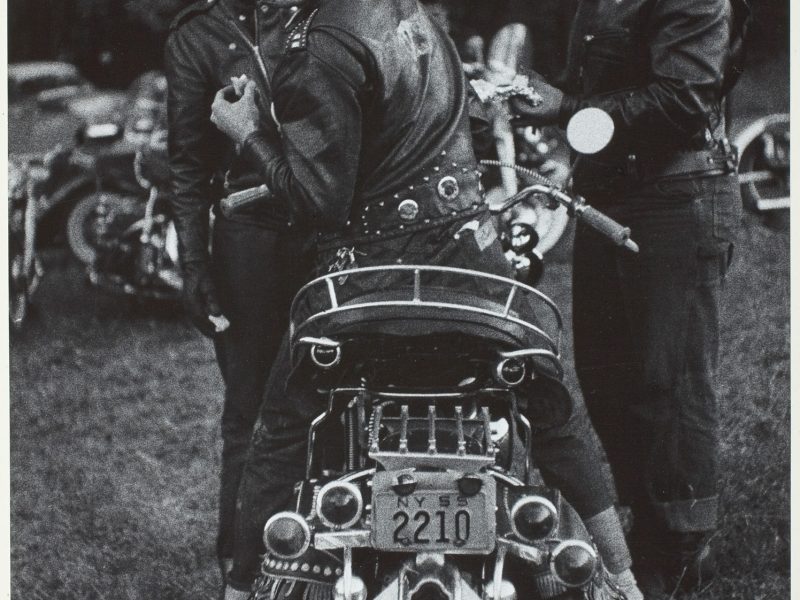

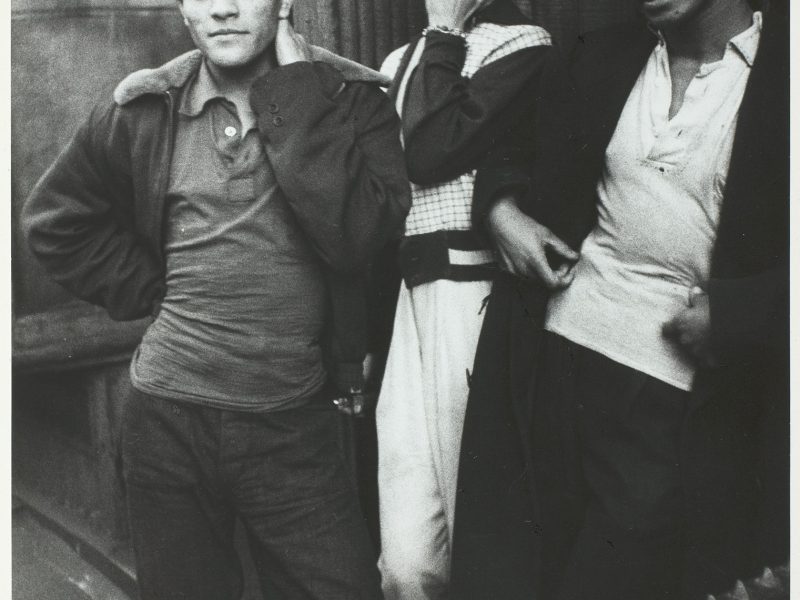

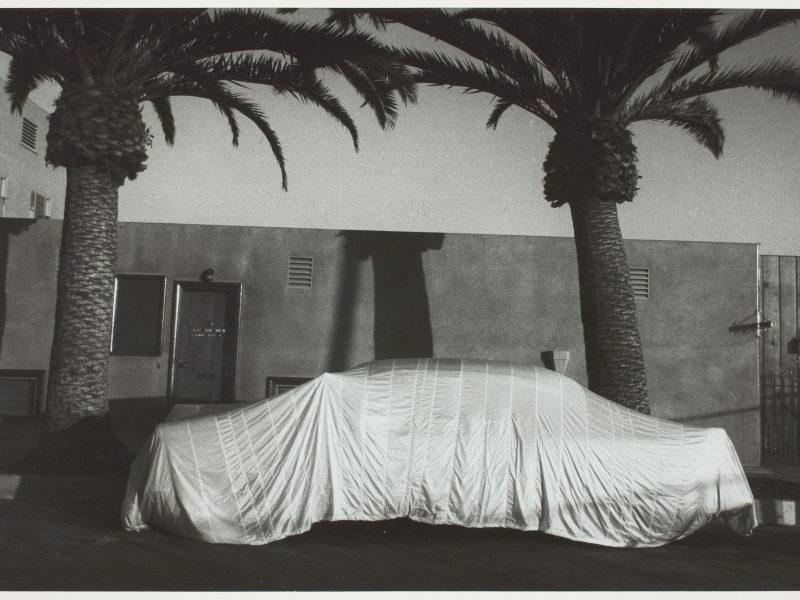

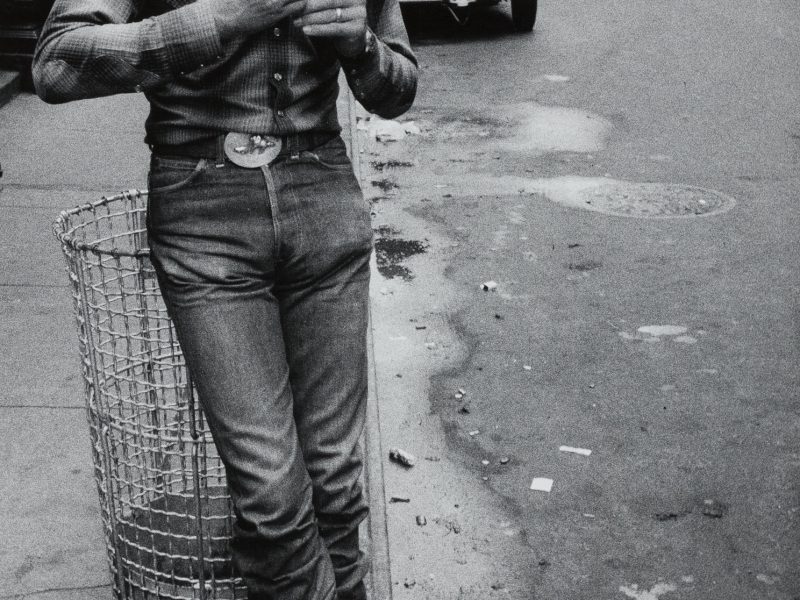

Robert Frank (American, born Switzerland 1924) began photographing while in Switzerland in the 1940s. In 1947, he immigrated to New York, where he worked for Alexey Brodovitch at Harper’s Bazaar, but soon quit to travel and photograph in Peru. Over the next several years he photographed in New York and Europe, documenting bankers in London and miners in Wales. In 1954, with a letter of support from Walker Evans, he applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship to drive across the United States and record its inhabitants. Between 1955 and 1956 Frank crisscrossed the country, producing more than twenty-five thousand images that he eventually would winnow down to eighty-three for his landmark photobook The Americans, published in France in 1958 and in the United States a year later.[1] Frank revealed a country made up of glowing jukeboxes and ubiquitous cars, lonely roads and crowded cities. Raw instead of polished, and honest instead of heroic, his pictures—including people from politicians to elevator operators to black mourners—exposed the fissures of American life in the 1950s, rejecting the clichés of postwar photography. Although initial reviewers disparaged the book and accused it of expressing an anti-American sentiment, The Americans galvanized photographers and indeed artists of all kinds and within a few years had become acknowledged as a classic. Uncomfortable with adulation and put off by hasty readings of his work, Frank turned for a time exclusively to cinema, making such acclaimed works as Pull My Daisy (1959) and Me and My Brother (1965–68). He returned to photography in the 1970s with rough, personal images while continuing to make films and books that frequently contrasted single and serial imagery.

Hugh Edwards stumbled across The Americans in a Greenwich Village bookstore soon after its publication. He responded instantly to the work, described by Beat poet Jack Kerouac in the book’s introduction, “With that little camera that he raises and snaps with one hand he sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film.”[2] In 1960 Edwards began a correspondence with Frank, with an eye toward an exhibition. “No other book, except Walker Evans’ American Photographs, has given me so much stimulation and reassurance as to what I feel the camera was created for,” he wrote him in May of that year. “I feel your work is the most sincere and truthful attention paid the American people for a long time.”[3]

Countering the often scathing early criticism, Edwards found freshness in Frank’s photographs and foresaw their broad acceptance. Frank, in turn, was grateful for the early support, mentioning it often in letters. “It makes one feel good to be appreciated so eloquently,” the photographer wrote Edwards in 1962. “I hope you will continue to feel so alive about what’s white and what seems to be black.”[4] In April 1961 Edwards organized Frank’s first solo museum exhibition and soon acquired thirty photographs from The Americans. For the curator, showing these images to the public was not a rarified exercise; on the contrary, he hoped his presentation would engender more empathy and understanding in human interaction. The wall label that Edwards wrote for the exhibition is worth quoting at length:

This book aroused more controversy than any collection of photographs published in recent years. The reasons for this may be the unusual merging of uncompromising reality and sincere poetry, the ability of the interpreter to appear as an actual participant and inhabitant of the environment he depicts, the natural and seemingly simple employment of technique and the surprising and undeniable presentation of people and sights which meet our eyes every time we go out of our houses and our vision is compelled to look beyond ourselves. It is a strong contribution to an American interpretation of life through the photographic medium and is another step forward in a great American photographic tradition, the earlier poets of which were Lewis Hine and Walker Evans. Perhaps it is an even larger accomplishment than anything that has gone before it because the average modern human being, in our age of distraction and acceleration, seems so difficult to approach, grasp and immobilize in interpretation. The camera is the most successful instrument for this task and yet there are few photographers who employ it successfully for this admirable purpose.[5]

[1] Robert Frank, Les Américains (Delpire, 1958) and The Americans (Grove Press, 1959).

[2] Jack Kerouac, introduction to The Americans, by Robert Frank (Grove Press, 1959), p. vi.

[3] Edwards to Robert Frank, May 23, 1960, Hugh Edwards Archive, collection of David and Leslie Travis, copy on file in the Photography Department, Art Institute of Chicago.

[4] Robert Frank to Edwards, Jan. 4, 1962, Hugh Edwards Archive, collection of David and Leslie Travis, copy on file in the Photography Department, Art Institute of Chicago.

[5] Edwards, exh. label for Photographs by Robert Frank, 1961, Hugh Edwards Archive, collection of David and Leslie Travis, copy on file in the Photography Department, Art Institute of Chicago.