Hans Bellmer.

La poupée (The Doll)

detail. Paris: Editions G.L.M., 1936.

Page 3 of 4

Hans Bellmer in The Art Institute of Chicago: The Wandering Libido and the Hysterical Body  Download PDF of entire essay for printing (1580k). Download PDF of entire essay for printing (1580k).

OTHER ESSAYS

Mary Reynolds: From Paris to Chicago to the Web

Warm Ashes: The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds

Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

|

|

Hans Bellmer in The Art Institute of Chicago:

The Wandering Libido and the Hysterical Body

The curvaceous form is hardly that of child, but neither the face nor the large hair bow seem to belong to a mature woman. An arm, leg, and breast are missing from the figure; still-life objects serve as their surrogates: a baguette substitutes for the arm, the table leg wears the matching boot, a milk pitcher doubles as a breast. Bellmer depicted the body as an amalgamation of the organic and inorganic, transgressing its normative limits to incorporate aspects of its environment. He fantasized the body as a series of shifting, interchangeable erogenous zones, subject to the forces of psychic repression in what he termed "the physical unconscious." Introducing this idea in "Notes on the Subject of the Ball Joint," he grouped his speculations around the image of a little girl sitting at a table:

Bellmer felt he must understand why certain parts of the body were absent from his imaginary girl's awareness. Using terms from psychoanalysis such as "condensation" and "displacement" to develop his theory, he proposed that, in the body's sense of itself, various parts can stand for or symbolize others. He reasoned that, because amputees retain awareness of their missing limbs, the images of the absent parts may be taken over by other areas of the body. The substitution of body parts one for another was of course the provocative technique underlying the permutations of his second doll, and here Bellmer ascribed the rationale for his method to the female figure itself: "It is in this way," he explained, "that the pose of the little girl must be understood; composing herself around the center 'armpit,' she is obliged "to divert consciousness from the center 'sex,' that is to say, from that which it was painfully forbidden or inopportune to gratify." Determined, as always, to investigate the female body, Bellmer believed himself to be analyzing its psychosexual dimensions. In his attempts to do this, he relied on the writings of Freud, familiar to all the Surrealists, and on the clinical studies of the Austrian psychiatrist Paul Schilder (1886–1940).[20]

Freud's model of the mobility of the libido provided the basis for Bellmer's theorizing about erotic feeling, which he projected onto the image of a "seated little girl." In his twenty-second introductory lecture on psychoanalysis, Freud observed that "sexual impulse-excitations are exceptionally plastic," and continued:

This capacity for displacement and the acceptance of surrogates, Freud stated, enables individuals to maintain health in the face of frustration.[22] As a creator of surrogates himself, inventor of virtual girls, Bellmer comprehended this capacity but located his own wandering libido in a female other. Schilder, too, remarked on the fluid Körperschema, or body image; and Lichtenstein has shown the importance of his book The Image and Appearance of the Human Body (1935) for Bellmer's thinking in this regard.[23] Intensely interested in the relationship between body and mind, the artist was attracted to the psychiatrist's stress on the inseparability of the two: early in his career, Schilder had concluded "that the laws of the psyche and the laws of the organism are identical"; he could not, therefore, describe "the symbolic interchange of organs by transposition" in the mental realm without adding that "there is no psychic experience which is not reflected in the motility and in the vasomotor functions of the body."[24]

This emphasis led eventually to Bellmer's presentation of his theory of a "physical unconscious" in his book Petite Anatomie de l'inconscient physique ou l'anatomie de l'image (Little Anatomy of the Physical Unconscious or the Anatomy of the Image) (Paris, 1957), in which he revived his description of the seated little girl and other portions of "Notes on the Subject of the Ball Joint."[25] He depended for a number of his insights on Schilder's clinical investigations of his patients' perceptions of their bodies, his work with amputees and their phantom limbs, and with hemiplegics who suffered paralysis of arms or legs due to strokes or brain lesions.[26] Schilder studied how impairment of the brain affects the ability to recognize or control parts of the body, and how, in some cases, inanimate objects, especially clothes and tools, may be incorporated into the body-image—as seen in Bellmer's illustration of the seated little girl whose doll-like body is additionally composed of a loaf of bread, milk jug, and table leg.

Hans Bellmer. Illustration for Oeillades ciselées en branche (Glances Cut on the Branch). Paris: Editions Jeanne Bucher, 1939. Heliogravure; 13.5 x 10.8 cm.

"One of the most important characteristics of psychic life," the psychiatrist asserted, "is the tendency to multiply images and to vary them with every multiplication." He invoked as an example the universal delight in imagining figures like Indian gods and goddesses with their many arms and legs.[27] Bellmer's myriad variations on the body of the doll might be taken as evidence of this psychic tendency expressed in the realm of sculpture; his later graphic work pushes this trend to an even greater extreme with the proliferation of limbs in his cephalopods—female heads with legs, often in stockings and heels—or with the octopuslike creature depicted in the Art Institute's Articulated Hands of 1954.

Hans Bellmer. The Articulated Hands, 1954. Color lithograph, ed. 32/59; 27.5 x 37.5 cm. Denoël 29. The Art Institute of Chicago, Stanley Field Fund (1972.32).

In this color lithograph, Bellmer conjured a figure made up of no fewer than seven arms and eight hands, the latter assuming affected positions with lifted pinkies and long, pointed nails. Remembering the sixteenth-century wooden dolls that spurred his obsession with the articulated joint (even their wrists and ankles, fingers and toes were adjustable), the artist treated each knuckle as a glowing ball joint. The hands seem thus bejeweled but also bony and strangely skeletal.

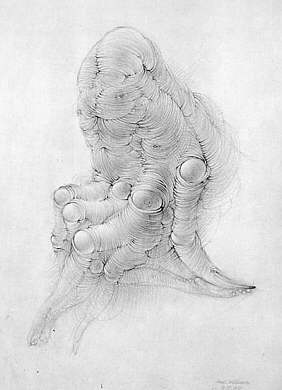

In the Art Institute's delicate pencil study of 1951 for another (unpublished) lithograph, Articulated Hand, Bellmer presented a hand that, because it also reads as a monstrous seated figure, assumes a gigantic scale.

Hans Bellmer. Untitled, 1951. Graphite on cream wove paper; 38.1 x 28.1 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago, Lindy and Edwin A. Bergman Collection (101.1991).

Indeed, the artist's inventive power is such that the hand, with its bent wrist and clawlike thumbnail, becomes on closer inspection a grouping of at least three figures—all headless, wrapped like mummies, with their exposed ball-joint bellies and knees emerging from the great hand's knuckles. Finger-legs extend gracefully en pointe, but a sense of struggle pervades the fused torsos that form the back of the hand and imply a face, with nipples and navel doubling as wary eyes and a tiny pursed mouth. Hands, eroticized and multiplied, appeared early in Bellmer's drawings as a favored motif, where finely rendered fingers touch ripe fruits and vaginal-looking orchids, or are interlaced by a winding snake.[28] Suggestive but ultimately conventional studies, these images gave way in the artist's oeuvre to more troubled and complex treatments of hands growing out of a human head, or altogether stripped of flesh and deathly.[29]

A series of untitled and undated photographs of real hands inextricably intertwined in sensuous embraces points again to Bellmer's interest in Schilder's researches into disturbances of bodily awareness.[30] Describing cases of agnosia and apraxia (inability to recognize and to move, respectively) of the fingers, the psychiatrist referred to the "Japanese illusion" to demonstrate the occurrence of agnosia even in the normally functioning brain and to show that optical stimuli contribute to, but do not fully determine, body image:

According to Schilder, "the body-image has to be built up again [in this exercise] when by the double-twisting the optic and tactile sensations have lost their clear structure." Bellmer's graphic and photographic depictions of hands duplicate the kind of confusion produced in Schilder's finger demonstration, with the viewer trying to negotiate the formal boundaries of each hand and its relationship to the image as a whole. As in the drawing and description of the seated little girl, Bellmer's aim here was to illustrate that body image is complexly constructed or experienced—and mutable.

An astonishing pair of hands made of pink bricks hovers like a giant butterfly in a beautiful ink-and-gouache drawing titled Child and Seeing Hands, made about 1950.

Hans Bellmer. Child and Seeing Hands, c. 1950. Pen and brown ink, gouache, and watercolor on paper; 23.8 x 28.5 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Randall Shapiro Collection (1992.196).

Surrealist in both iconography and technique, this drawing from the Art Institute's collection is an example of the decalcomania process Bellmer had learned from Oscar Dominguez in 1940. In this technique, the medium (ink, watercolor, or paint) is applied to a sheet of paper; the sheet is covered with another piece of paper, and the two are pressed or rubbed together. When the second sheet is pulled away, a textured surface is revealed, full of chance effects in which the artist can discover and develop serendipitous images, Rorschach-style. Upon the rich, spongy field Bellmer created by these means for Child and Seeing Hands, a girl in a pleated white dress, striped hose, and boots appears, running with her pink hoop toward the vision of flying hands and an odd brick chimney spewing white vapors. While the child in her anachronistic costume is by now a familiar motif in Bellmer's repertory, and the sexual symbolism of the smokestack is obvious, what can be the meaning of hands with too many fingers and mysterious brown eyes that gaze out from their palms?

Next >

Next >

Page 3 of 4

Hans Bellmer in The Art Institute of Chicago:

The Wandering Libido and the Hysterical Body

OTHER ESSAYS

Mary Reynolds: From Paris to Chicago to the Web

Warm Ashes: The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds

Documents of Dada and Surrealism:

Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

Essays | Works of Art | Book Bindings | Related Sites | Finding Aid | Search Collection

|

|