Hans Bellmer.

La poupée (The Doll)

detail. Paris: Editions G.L.M., 1936.

Page 4 of 4

Hans Bellmer in The Art Institute of Chicago: The Wandering Libido and the Hysterical Body  Download PDF of entire essay for printing (1580k). Download PDF of entire essay for printing (1580k).

OTHER ESSAYS

Mary Reynolds: From Paris to Chicago to the Web

Warm Ashes: The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds

Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

|

|

Hans Bellmer in The Art Institute of Chicago:

The Wandering Libido and the Hysterical Body

A passage in Bellmer's Anatomie de l'image mentioned above provides the answer.[32] Discussing again the situation of his seated little girl who represses awareness of her sexual parts and transfers it instead to her armpit, the artist asserted the normality of this phenomenon. He wished, however, to introduce extreme, clinical examples of such displacements, and to do this he drew on the dated accounts of the Italian criminologist and physician Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909). Citing the latter's "Transferences of Sensation in Hysteria or Hypnosis,"[33] Bellmer offered cases of adolescent girls whose body images and behavior were severely disturbed by the onset of puberty: one girl's hysterical symptoms included convulsions, hyperaesthesia, and sleepwalking; she became blind but gained the capacity to see through her nose and left ear. "These phenomena," Bellmer continued, "are not isolated":

Child and Seeing Hands seems quite directly related to these case studies of female hysteria. Like Breton and Louis Aragon, who had celebrated "The Fiftieth Anniversary of Hysteria" in the pages of La Révolution surréaliste in 1928, Bellmer was fascinated by concepts of psychic disorder.[34] From the point of view of Surrealism, hysterical symptoms constituted the body's form of automatic writing, an involuntary protest against societal restrictions placed on sexuality. Entrenched for centuries in gender stereotypes—as rational males attempted to fathom the "mysteries" of an unruly female sex—hysteria also fueled Bellmer's long-standing interest in another puzzle: the relation of mind and body.[35]

He drew, as we have seen, from Schilder's studies of brain and body image, but also followed Freud on the sexual etiology of the neuroses and incorporated the vocabulary of psychoanalysis in his work. In Child and Seeing Hands, the artist literalized the notion of psychic "defense" with a wall of bricks, and even speculated in Anatomie de l'image about the kind of trauma that might have caused Lombroso's girl to develop the specific symptoms referenced in his drawing:

For Lichtenstein, Bellmer's "account of the materialization of hysterical conversion symptoms" also relates "to the distortions to which he subjected the body of the doll."[36] Indeed, many photographs of the second doll, especially those depicting its four-legged incarnation convulsed on a bare floor or bed or arched over in a kind of back bend,[37] recall the thrashing bodies of hysterics documented by the famous nineteenth-century neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot at the hospital of the Salpêtrière in Paris. Charcot's records, graphic and photographic, helped him to observe and systematize the different stages of hysterical attacks; among the characteristic postures he identified was the arc en cercle, or rainbow pose, with the back arching and both head and feet firmly planted on the ground or (more often) the bed.[38] In a turn-of-the-century romance about the Salpêtrière, one of Charcot's students, Jules Claretie, described a patient enduring one of these seizures—adopting an analogy that uncannily predicts Bellmer's doll: "The human being seemed reduced to the state of a machine, to one of those 'maquettes' of wood that sculptors use, bending the joints of these mannequins all around as they please—macabre caricatures of man."[39]

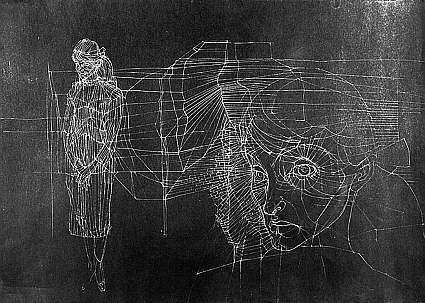

Hans Bellmer. Untitled (Double-Sided Portrait of Unica Zürn) (verso), 1954. Pen and white ink on black wove paper; 50 x 70 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of George A. Poole (1967.245).

Sadly and ironically, such attacks were witnessed as well, decades later, by someone whom Bellmer knew intimately, the German Surrealist writer Unica Zürn. In 1954, a year after Bellmer met her on a visit to Berlin, Zürn moved to Paris with him, and the artist captured her in a typically somber, pensive mood in a portrait now in the Art Institute's collection. On the verso of the sheet, a large, double-sided white-ink drawing on black paper, Zürn is shown standing, head lowered, eyes downcast, hands folded demurely in front of her, and dressed in a modest suit. A network of lines and bricks animates the background, while to the right, closer to the picture plane but also implicated in the abstract web, Zürn's face emerges in three-quarter view. Inexpressive and wide-eyed, she wears her hair tied back with a bow. Although photographs from the 1950s indicate Bellmer's relative faithfulness to Zürn's appearance in this likeness, his obsessive fantasy subsumes her image on the drawing's recto, the side he chose to sign and date.

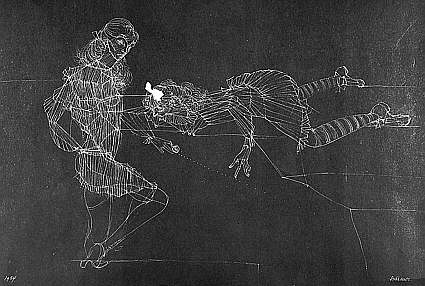

Hans Bellmer. Untitled (Double-Sided Portrait of Unica Zürn) (recto), 1954. Pen and white ink on black wove paper; 50 x 70 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of George A. Poole (1967.245).

Here Bellmer transformed her into a femme-enfant, awkwardly displayed in a fanciful, transparent, pleated dress reminiscent of the one worn by the girl in Child and Seeing Hands; he also depicted her on all fours in striped stockings and Mary Janes. In the latter pose, the figure plays with a cat's-eye marble—a motif Bellmer introduced twenty years earlier in "Memories of the Doll Theme." Her pink hair-bow is real, the drawing's single collage element and a staple feature in Bellmer's iconography of little girls.

Zürn left Bellmer temporarily in 1960 and returned to Germany. There she was admitted for the first time to a mental institution, diagnosed as schizophrenic. In the decade remaining to her, she was hospitalized intermittently in France, where she continued to live with Bellmer and to produce autobiographical texts, including the important Der Mann im Jasmin: Eindrücke aus einer Geisteskrankheit (The Man in the Jasmine: Impressions from a Mental Illness) and Dunkler Frühling (Dark Spring). In her writings, Zürn presented a poignant picture of illness from within the institution, from the point of view of the patient, which stands in contrast to the constructions of female madness in the diverse work of Charcot, Claretie, Breton, Aragon, and Bellmer.[40] At moments, however, she thought of Bellmer's monstrous inventions in terms of what she saw around her, detecting in the body of a fellow patient "a connection with his celebrated 'Cephalopod,' the woman with head and legs and without arms."[41] Speaking of herself in the third person, Zürn related:

During the course of their difficult relationship, Bellmer and Zürn collaborated in a number of ways, he providing postscripts and frontispieces for her publications, she posing for drawings and at least one painting.[43] In 1958 he made a group of shocking black-and-white photographs of her naked torso bound tightly with string, transforming her body into a series of folds and bulging mounds of flesh. One of these was reproduced on the cover of Le Surréalisme, même that year: showing Zürn reclining on a bed, seen from behind without head, arms, or legs—leaving only a pale lump of trussed meat—the image bears the necrophilic caption "keep in a cool place."[44] Like all of Bellmer's work, these photographs manipulate and distort the female body for the purposes of a complexly motivated male imaginary. Zürn was not the only model ever to place herself in the service of this compulsive project, but her tragic psychological vulnerability, which culminated in suicide in 1970, renders it especially disturbing. Reflecting on Bellmer's creative endeavors, she pointed to his extraordinary technical facility, "infinite gentleness," and circumspection, and yet admitted that the person "who is sketched by him, or photographed...by his pencil [sic] participates with Bellmer in the abomination of herself. Impossible for me," she concluded chillingly, "to render him greater praise."[45]

Page 4 of 4

Hans Bellmer in The Art Institute of Chicago:

The Wandering Libido and the Hysterical Body

OTHER ESSAYS

Mary Reynolds: From Paris to Chicago to the Web

Warm Ashes: The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds

Documents of Dada and Surrealism:

Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

Essays | Works of Art | Book Bindings | Related Sites | Finding Aid | Search Collection

|

|