Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession/291

1905–1917

291 Fifth Avenue

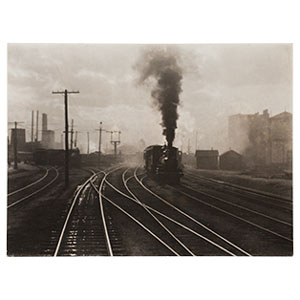

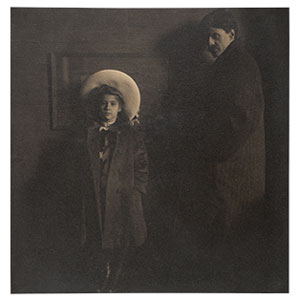

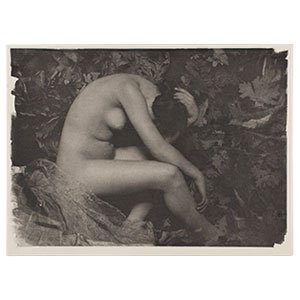

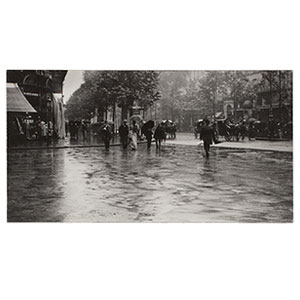

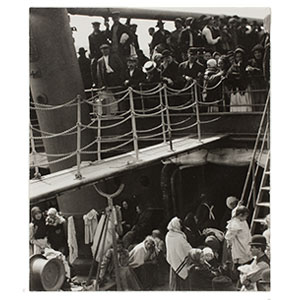

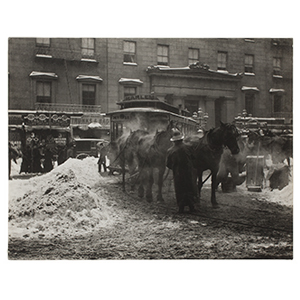

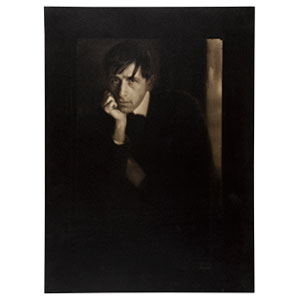

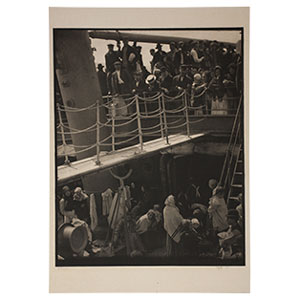

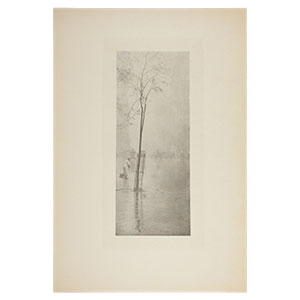

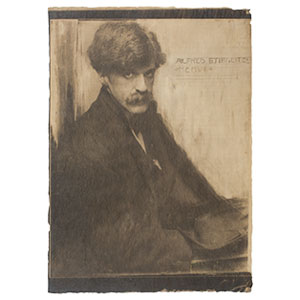

The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession—later known as 291—began as a place to display and experience the latest developments in photography, and ended up being the first American foothold for modern art of all media, from the work of the European avant-garde to that of a new generation of American painters. Alfred Stieglitz announced the founding of the gallery in 1905, promising “small, but very select, shows,” displayed “in a manner worthy of Secessionist methods.”[1] It opened with an exhibition of Photo-Secessionists’ work in November of that year in rooms secured and designed by Edward Steichen at 291 Fifth Avenue, and the space soon became a destination for intellectuals and artists, who engaged in freewheeling discussions in addition to viewing the art on display.

After a series of photography exhibitions in 1905 and 1906, Stieglitz started to exhibit works in other media, showing pieces by some of the most important names in modern European art even before the 1913 Armory Show, which was a turning point for awareness of modern art in America. The gallery hosted exhibitions by artists including Auguste Rodin, Henri Matisse, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Francis Picabia, and Constantin Brâncusi—many of which were the artists’ American debuts. Stieglitz also began showing the work of a group of American painters including John Marin, Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, and Georgia O’Keeffe, whom he would champion for the rest of his career. After 1913, when he showed an exhibition of his own photographs concurrent with the influential Armory Show, Stieglitz no longer hung photography at 291, making an exception for the prints of a young Paul Strand in 1916.

For the July 1914 issue of Camera Work, Stieglitz posed the question, “What is 291?,” and sixty-five artists, critics, and collectors sent in their responses in poetry and prose. A representative reply came from photographer Francis Bruguière, who wrote, “If you go there often enough you will find just how big or how small you are. Sometimes the awakening comes as a shock. But after all it is an oasis in the desert of American ideas.”[2]

With the dissolution of the Photo-Secession, the end of Camera Work, and the uncertainty brought about by the United States’s entry into the First World War, a gallery devoted to the exploration of aesthetic principles had became increasingly unsustainable, and in 1917, Stieglitz closed 291. It would not, however, be his last gallery: at Anderson Galleries, and then at An American Place, he would continue to champion his definition of modern art.

[1] Alfred Stieglitz, “Letter to the Members of the Photo-Secession,” Photo-Era 15 (Oct. 1905), reprinted in Richard Whelan, ed., Stieglitz on Photography: His Selected Essays and Notes (Aperture, 2000), p. 178.

[2] Francis Bruguière, “What 291 Means to Me,” Camera Work 47 (July 1914), p. 29.