Man Ray

(Emmanuel Radnitzky)

(American, 1890–1977).

Mary Reynolds, 1930.

Page 2 of 4

Warm Ashes: The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds

Download PDF of entire essay for printing (1282k). Download PDF of entire essay for printing (1282k).

OTHER ESSAYS

Mary Reynolds: From Paris to Chicago to the Web

Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

Hans Bellmer in The Art Institute of Chicago: The Wandering Libido and the Hysterical Body

|

|

Warm Ashes:

The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds

Mary Reynolds: "Reliure"

In the 1920s, women in search of a fashionable vocation in the arts turned increasingly to bookbinding. In 1929, Mary Reynolds followed this trend and studied bookbinding in the atelier of master French binder Pierre Legrain.[19] With the patronage of prominent Paris couturier Jacques Doucet, Legrain had become one of France's most innovative and influential bookbinders of the early twentieth century. Although trained as a decorator and furniture designer, Legrain developed a new vocabulary of ornament in bookbinding that was decidedly fresh and contemporary. He introduced innovative materials that were lavish and exotic: precious gems and metals, skins such as lizard, python, and even crocodile and shark.[20] Legrain viewed the book cover as a continuous plane upon which to place his designs. He explored the design possibilities of typographic form, placing varying fonts and letters in modernist juxtapositions. The influence of De Stijl, which was emerging in the Netherlands during the same time Legrain was developing his design tenets, can be seen in his nontraditional approach, simplification of design elements, and use of geometric devices. Prior to Legrain's sweeping modernization, French bookbinders had copied the ornate and elaborate bindings of the Louis XIV period, with its complex tracery and elegant materials. The modern style introduced to bookbinding by Legrain was rapidly and enthusiastically embraced by French connoisseurs and collectors and widely imitated by other bookbinders.

Jacques Doucet and Duchamp had been friends since the early 1920s. It is likely that it was through this connection that Reynolds became an apprentice in the most fashionable and busiest bookbindery in the city. Reynolds spent just one year in Legrain's atelier—long enough to learn the basics of book construction. Because Legrain was a designer, not a binder, artisans in his atelier realized his designs. Reynolds, therefore, would have studied the craft itself directly with binders in his employ; she learned the language of design, however, from Legrain himself. One sees this in her nonconformist use of exotic materials and her manipulation of letterforms.

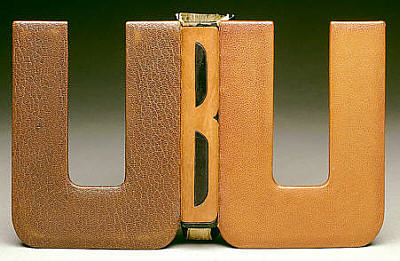

Over the next decade, Reynolds refined her skills, binding only for friends. Kathe Vail, the daughter of the writers Laurence Vail and Kay Boyle, remembered that "Mary Reynolds made a beautiful binding for [Laurence Vail's 1931 novel] Murder! Murder!"[21] Later, Henri-Pierre Roché was so taken with a binding that she executed for his book Don Juan that he considered asking her to bind his son's personal illustrated diary. It was during this period that Reynolds and Duchamp undertook their first recorded collaborative work. In 1935, they conceived and executed a binding for Alfred Jarry's Ubu Roi.[22] By January 1939, Reynolds felt comfortable enough with her work to list her occupation as "Bookbinder" on her business cards: MARY REYNOLDS / RELIURE / 14 R. HALLÉ, PARIS XIV.

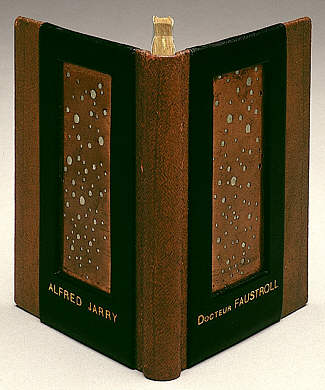

Fortunately, Reynolds did not have to live on the income from her bookbinding business. Although often referred to as an "heiress," Reynolds, in fact, lived simply on the income from a modest trust established by her parents and her pension as a war widow. Because she did not have to work, she could experiment and explore her chosen medium. Her involvement with Dada and Surrealism and passion for new ideas enabled her to develop a remarkable visual vocabulary. Duchamp described her bindings as being "marked by a decidedly surrealistic approach and an unpredictable fantasy."[23] Reynolds's technique, however, did not always equal her artistic ideas—a matter of concern to Duchamp when he and Brookes Hubachek began considering what to do with her oeuvre after her death. The artist expressed to her brother the "hope that you will find a place where they will be kept together as artistic bindings although the 'specialists' might object to the liberties Mary sometimes took with the technical achievement."[24] Reynolds focused on the design, regardless of whether the binding structures worked well. Her ingenuity was not bound by tradition. She followed in the manner of Legrain, considering the covers and spine of the binding to be a single, continuous plane upon which to work. Reynolds considered the design both two-dimensionally, as in the case of Raymond Queneau's Odile, as well as three-dimensionally, as is the case of Jarry's Docteur Faustroll.

Docteur Faustroll

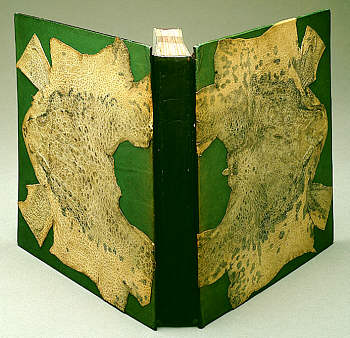

Legrain felt that the binding should relate to the contents of the work it contained, that it should "evoke not the flower, but its fragrance."[25] Reynolds subscribed to that theory on most occasions, though frequently with a twist, as in the binding for Brisset's Le Science de dieu or the Man Ray/Paul Éluard work, Les Mains libres.

Le Science de dieu

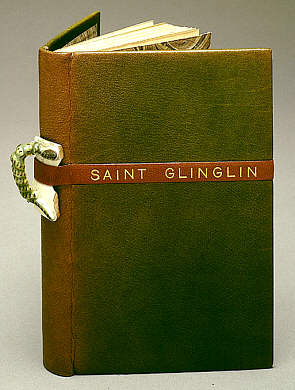

In other cases, such as Queneau's Saint Glinglin, it is very difficult to relate the design of the binding to the intellectual content of the book.

Saint Glinglin While Legrain's influence is important, Reynolds's ironic wit and Duchamp's artistic ideals and the resulting Surrealist vocabulary most define her work. The pun was one of Duchamp's favorite devices. Reynolds borrowed this tool from him with great success in a number of her extraordinary bindings. For instance, while creating the drawings used in Les Mains libres, Man Ray described his hands "as dreaming."[26] Reynolds created a physical pun by placing delicate kid gloves slit open and laid on the front and back covers of the binding. The cut-open gloves symbolically freed the hands and allowed them to dream.

Les Mains libres

She employed the pun again for Jarry's Le Surmâle with her use of a metal corset stay bursting out of a delicate butterfly.

Le Surmâle

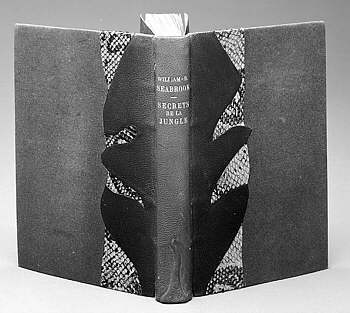

Secrets de la jungle The application of boa-constrictor skin to create the fronds of a jungle plant on William Seabrook's Secrets de la jungle juxtaposes the fear associated with the large jungle reptiles with the cool protection afforded by the jungle canopy. Reynolds created an illusion of danger with her choice of materials.

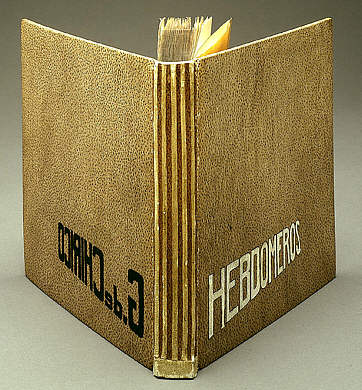

It is difficult to assess fully the significance of Reynolds as an artist because of unresolved questions about Duchamp's role in the conception of these works. That he had a role is certain; the extent and import of his involvement is the issue. Some of the collaborative works of Reynolds and Duchamp, such as Ubu Roi and Hebdomeros, are well documented in the literature about Duchamp.

Ubu Roi

Hebdomeros

Other projects clearly appear to be the result of their working together on the concept. The binding for Docteur Faustroll, for example, conceptually speaks Duchamp's language, specifically suggesting his Fresh Widow (1920; The Museum of Modern Art, New York). Duchamp, himself, always attributed the success of the bookbindings to Reynolds's wit and talent. On only a few occasions did he reveal his own contributions to the creative process. While he may not have had an active part in the design of all Reynolds's bindings, one must assume his influence was at least subliminal.

Next > Next >

Page 2 of 4

Warm Ashes: The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds

OTHER ESSAYS

Mary Reynolds: From Paris to Chicago to the Web

Documents of Dada and Surrealism:

Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

Hans Bellmer in The Art Institute of Chicago:

The Wandering Libido and the Hysterical Body

Essays | Works of Art | Book Bindings | Related Sites | Finding Aid | Search Collection

|

|