Man Ray

(Emmanuel Radnitzky)

(American, 1890–1977).

Mary Reynolds, 1930.

Page 3 of 4

Warm Ashes: The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds

Download PDF of entire essay for printing (1282k). Download PDF of entire essay for printing (1282k).

OTHER ESSAYS

Mary Reynolds: From Paris to Chicago to the Web

Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

Hans Bellmer in The Art Institute of Chicago: The Wandering Libido and the Hysterical Body

|

|

Warm Ashes:

The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds

The Final Years: 1943–1950

Reynolds and Duchamp stayed in New York for the duration of the war, taking up residence once again in Greenwich Village.[52] They socialized with old friends and other artists exiled in New York, such as the Frederick Kieslers and Alexander Calder. In California, a surprised Man Ray received the role of paintings Reynolds had rescued. He was especially delighted that Observatory Time—The Lovers, now known as The Lips (1932–34; private collection), was among them.[53]

By July 1944, Reynolds was well enough to begin looking for employment. Fine bookbindings were not in demand; in any case, rationing meant that materials she needed were reserved for military use. She received her Civil Service rating and applied for a job with the O.S.S. She hoped that her experience in the French Résistance and facility with languages, including French, German, and Italian, would be of assistance in procuring a job with the foreign service. The interviewer reported her to be, "Tall, good appearance, alert and a little bit the aggressive type."[54] Although several letters were written on her behalf by some of her brother's government contacts, and she gained a security clearance, Reynolds was not assigned a position. On August 18, 1944, Major S. W. Little reported the "File sent to MO Registry as of 27 July marked no interest (age)." Mary Reynolds was fifty-two at the time.

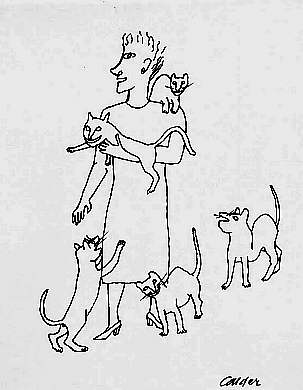

Although Reynolds had always planned to return to Paris after the war, Duchamp wished to remain in New York. He found the pace, the scale, and the opportunities among American collectors inordinately seductive. Once again, he tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade Reynolds to stay with him, this time in New York. Calder remembered that a "moulting cat adopted her on 11 St., and Marcel thought that might well be the means of keeping her in America."[55] Her love of cats notwithstanding, Reynolds returned to Paris six weeks after the end of the war. She was euphoric to be home at 14, rue Hallé, among her books, her furniture, her cats. Although Duchamp rejoined her in 1946, the pull of New York was too great. Reynolds wrote of her "anguish" to their mutual friends, the Hoppenenots.[56] Duchamp's departure in early January 1947 left Reynolds widowed again, albeit happy in her adored Paris.

Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976). Mary Reynolds with Her Cats, c. 1940s. Pen and black ink, on white wove paper; 36.8 x 29.2 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Frank B. Hubachek (1957.82). From 1945 to 1947, Reynolds was the Paris representative for the avant-garde magazine View, soliciting among her artist and writer friends for the editor Charles Henri Ford. Correspondence between Reynolds and Ford reveals many of the well-known problems, especially that of cash flow, associated with this short-lived but influential publication. In a letter to Ford, Reynolds wrote, "So for months I've been murmuring VIEW and feeling like a worm. For an American to beg material which the French pay for is not at all a nice position."[57] She approached writers such as Jean Genet and André Malraux and old friends like Jean Cocteau and Georges Hugnet. She worked tirelessly and enthusiastically; a postscript to a March 3, 1946, letter to Ford reads, "VIEW seems to bloom. 3VVVs for VIEW."[58]

Reynolds does not appear to have continued her bookbinding to any great extent upon her return to Paris. Saint Glinglin appears to be one of the few bookbindings that she created in this period. Perhaps she needed the synergy that Duchamp provided or perhaps the magic of the moment was over. The war had altered not only the physical landscape of Europe, but the milieu of the artists as well. The revolution that was Surrealism was being rapidly eclipsed by a new wave of artists kindling the flames of abstraction. The central figures of Surrealism had been scattered all over the globe as well. Some, like Duchamp, stayed in the United States after the war. Others returned to a Europe whose spirit had been catastrophically broken and would need years to heal. Breton had seen his influence significantly diminished while he was in New York. Reynolds herself seems to have lost the passion for her art. That spot in her soul was filled instead with the quiet guilt of a survivor and the serenity often found in one's advancing years. Reynolds's health had also been broken by the deprivations of the war and the hardships endured during her escape. In June 1949, she traveled to La Preste to take a cure. In a postcard to Flanner, she wrote, "We pass 21 days of insomnia, fluttering heart, stomach and nerves and constipation—hoping to kill the coli bacilli before we succumb."[59] The mineral waters of La Preste were believed by many to kill intestinal bacteria coli bacilli. Flanner noted at the bottom of the postcard, "Nearly last words from dear Mary."

By April 1950, Reynold's health had deteriorated to the point that she checked into the American Hospital in Neuilly. Upon learning this, Duchamp became acutely concerned; he queried all of their friends in Paris for information about her condition. Of Roché, he asked, "Is it only the kidneys, or kidney? Strange that the infection is not vanishing, even gradually."[60] He asked the Crottis to keep him informed. In a subsequent letter to Roché, Duchamp speculated, "I have never uttered the word cancer, but do you think that there is a dreadful possibility there? Don't hesitate to tell me."[61] Duchamp finally made the voyage to France at the end of September. He found Reynolds's condition desperate. "Her brain is so lucid, her heart and her lungs are in an almost perfect state, that one hardly understands that it is impossible to attempt anything in the way of a 'cure.'"[62] A visit to the clinic at Neuilly revealed Reynolds "had a dreadful tumour [of the uterus] which no one detected and cannot now be operated."[63] Her condition was hopeless. Four days after Duchamp arrived at her bedside, she slipped into a coma. At 6:00 a.m. on September 30, 1950, Mary Reynolds died at home on rue Hallé, with her beloved Marcel Duchamp at her side. Her funeral was held on October 3 at the American Cathedral on the Avenue Georges V.

Duchamp stayed on at 14, rue Hallé taking care of Reynolds's affairs, cleaning the house, and most importantly, organizing her bindings, as well as the books, art, and ephemera that she had gathered during her three decades in Paris. These he had carefully packed and shipped to her brother, who had decided to donate the collection to The Art Institute of Chicago in his sister's memory. Hubachek and Duchamp worked assiduously on the organization and publication of the collection for nearly six years. When the collection catalogue, Surrealism and Its Affinities: The Mary Reynolds Collection, was published in 1956, Hubachek made certain that as many of his sister's friends as he could locate received a copy. He obtained names and addresses not just from Duchamp, but from Cocteau, Barnes, Calder, Flanner, and others. Tributes poured in. One of the most touching was from Cocteau, who wrote to Duchamp, "My very dear Marcel—It is rare that death leaves warm ashes. Thanks to you, this is what is happening for Mary. I congratulate and embrace you."[64]

In a letter to Hubachek, Flanner captured the love and admiration Mary Reynolds had inspired from so many in her life. The Mary Reynolds Collection is all that Brookes Hubachek and Marcel Duchamp envisioned. As a core collection of published materials by the Surrealists, the five hundred printed pieces include all of the important documents of Surrealism, as well as a multitude of ephemera, so much of which might otherwise have been lost. But Mary Reynolds's true legacy is that part of the collection that contains her magical bindings, an output of fewer than seventy books. It is in these remarkable works that the spirit of Mary Louise Reynolds lives on.

Page 3 of 4

Warm Ashes: The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds

OTHER ESSAYS

Mary Reynolds: From Paris to Chicago to the Web

Documents of Dada and Surrealism:

Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

Hans Bellmer in The Art Institute of Chicago:

The Wandering Libido and the Hysterical Body

Essays | Works of Art | Book Bindings | Related Sites | Finding Aid | Search Collection

|

|