Man Ray

(Emmanuel Radnitzky)

(American, 1890–1977).

Mary Reynolds, 1930.

Page 3 of 4

Warm Ashes: The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds

Download PDF of entire essay for printing (1282k). Download PDF of entire essay for printing (1282k).

OTHER ESSAYS

Mary Reynolds: From Paris to Chicago to the Web

Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

Hans Bellmer in The Art Institute of Chicago: The Wandering Libido and the Hysterical Body

|

|

Warm Ashes:

The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds

The 1930s

The 1930s marked a period of tranquillity, contentment, and artistic achievement for Reynolds. Her relationship with Duchamp had settled into a comfortable intimacy. Her creativity and binding production were at their highest levels. She held an open house almost nightly at her home at 14, rue Hallé, with her quiet garden the favored spot after dinner for the likes of Duchamp, Brancusi, Man Ray, Breton, Barnes, Guggenheim, Éluard, Mina Loy, James Joyce, Jean Cocteau, Samuel Beckett, and others.

Man Ray. Photograph of Mary Reynolds, c. 1930s.

Ever protective of his independence, Duchamp always maintained a separate small studio. Even so, he spent most of his time at rue Hallé, and the interior of Reynolds's home was one of their most public collaborations. Man Ray described Duchamp as taking an interest in "fixing up the place, papering the walls of a room with maps and putting up curtains made of closely hung strings, all of which was carried out in his usual meticulous manner, without regard to the amount of work it involved."[27] Anaïs Nin recalled visiting "Marcel Duchamp and his American mistress. A studio full of portfolios, paintings, and her collection of earrings hanging on the white walls, earrings from all over the world, so lovely, every beauty of design duplicated by a twin, some of them twinkling, some cascades of delicate filigree, some heavy and carved."[28] Peggy Guggenheim remembered lovely furniture, maps everywhere, a lighted globe of the earth.[29] One wall was painted a deep blue, with tacks placed at different angles connected with string. The comparison with Reynolds's garden must have been remarkable: an elegant, kinetic interior contrasting with the serene, cool exterior.

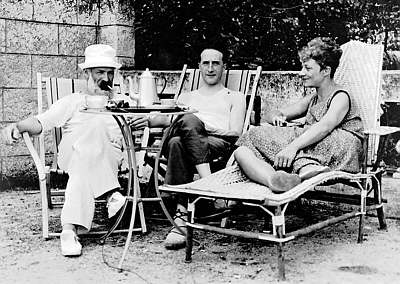

Constantin Brancusi, Marcel Duchamp, and Mary Reynolds at Villefranche, France in 1929.

The War Years: Occupation and the French Résistance

This idyllic lifestyle was not to last, however. In Germany, the rise of Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist Party threatened the European continent. While Reynolds and Duchamp kept an eye on the approaching menace, the rapidity with which their world changed when the Nazis occupied France caught them by surprise. It is difficult to imagine such free spirits living under the tyranny of Nazi-occupied Paris. Those who could, fled; a few stalwarts stayed. Mary Reynolds was among that latter group. Duchamp was far more pragmatic. He made a decision the day after Holland fell to leave for Arcachon on the Bay of Biscay, southwest of Bordeaux.[30] From that time until he was finally able to leave for New York in 1942, Duchamp attempted in vain to coerce Reynolds into leaving her home and cats in occupied Paris and joining him variously in Arcachon, Marseilles, and Sanary-sur-Mer. In a letter to her brother, he triumphantly announced that he had managed to procure a permit that allowed travel into the Unoccupied Zone and was valid for three months and several trips. His intent was to return to Paris whenever possible and prudent to visit Reynolds. He lamented her stubborn refusal to move and listed for Hubachek her many excuses, in Reynolds's own words: "'Don't worry, no torture, no boats for six months....Conditions acceptable here and no excitement.'"[31]

Man Ray. Photograph of Mary Reynolds, c. 1930s. Duchamp termed such excuses "nonsense." He voiced hope that Reynolds would consent to follow him and spend the summer in the Unoccupied Zone. Reynolds, clearly unenthusiastic about such a plan, wrote to her brother: "To keep peace in the family, I am taking steps to join him for a month's vacation. Probably quite futile but nevertheless steps."[32] In another letter, Reynolds sent the following message to Hubachek: "Could not cross ocean, too scared, very comfortable here."[33] She was, in fact, content at rue Hallé. Her garden was yielding beans, cabbages, carrots, onions, and potatoes; the fireplace was still supplied with wood. Early in the Occupation, Reynolds had written to Hubachek that she was "hoping to do a lot of binding."[34] Unfortunately, that was not to be the case. Binding materials were in short supply; the everyday ordeal of living ate up time. Reynolds writes, "I am busy as that one armed painter....also warm and I believe fattening. Am threatened with a job of book-binding but don't know where I'd find the time. Also well out of practice."[35] In an earlier letter to Hubachek, Reynolds had commented, "But even with life reduced to its most primitive form—or because of it—there is so little time."[36] She conceded that she spent much time "tracking down food and [giving] unorganized aid."[37] The "unorganized aid" existed in two forms: financial support of a myriad of friends through a complex system involving dozens of people, and an active role in the French Résistance.

The French Résistance was a secret organization of patriots devoted to undermining the Nazi regime and gaining back France's independence. Along with Samuel Beckett, Gabrielle Buffet (formerly Picabia), and Suzanne Picabia, Reynolds was a leader in the Résistance in Paris, giving refuge to those fleeing Nazi persecution and imprisonment and passing information to the Allies. Gabrielle Buffet remembered, "Around 1941, I began to work with the French Résistance. Mary was the only one to keep papers and documents at home."[38] For someone whose code name was "Gentle Mary," Reynolds was extremely courageous. Her compassion for those in need was further heightened during this period. While writing again to her brother about her contentment in Paris, Reynolds commented, "The only draw back is that the force that would otherwise make me a good life is such a black and ugly one that it can't be ignored even in retreat—and the fact that so much misery exists is sometimes overwhelming."[39]

The artist Jean Hélion was one of those whom Reynolds helped. "I was extremely fond of her, and much indebted to her. She hid me in her house in Paris for 10 days, after I had escaped from a German prisoners' camp, in 1942; when she herself was under police supervision, and she was then running a serious risk. So charming, lovely, and alive, and brave discretely [sic]."[40] Reynolds, herself, was quite circumspect about her Résistance activities in her communications home. Completely committed to the cause, she refused to do or say anything that might compromise her colleagues in the Résistance or their activities.

In trying to explain her stubborn refusal to leave Paris, even in the face of such peril, Reynolds wrote, "For the moment I have a strong feeling that anything I do will be wrong and visiting the sick and caring for the forgotten is just my job—as long as it lasts. I can't seem to leave it of my own free will. Must be a drop of protestant blood coming out late in life."[41] In contemplating the "frenzy" so many were experiencing, Reynolds wrote, "I am trying to profit by the times here....it is a bill in my personal life. I said try—don't laff—to make myself a better character—a little late. It is a curious life of anguish and such luxury as I have not known for a long time—the evenings more or less alone and away from the world like a desert island—and I enjoy that."[42] Her brave work in the Résistance and the care that she gave others provided her with both the anguish and luxury of which she spoke. It was only when the Gestapo was actually at her door that Mary Reynolds fled her beloved Paris.

Throughout the Occupation, Reynolds's friends continued to worry about her safety, frequently contacting both Hubachek and Duchamp for news and reassurance. By 1942, as the war deepened and Hitler's hold on Europe strengthened, concern was at its height. Kay Boyle's query of Brookes Hubachek was typical: "I was anxious to have some news of Mary. Naturally, all of those of us who love Mary are worried about her increasingly now."[43] Along the same line, Peggy Guggenheim wrote, "Do you have any news of Mary? Is she allright?.... I wish Mary would come [here] too. But I guess she won't and maybe it is too late."[44] Correspondence between Hubachek and Duchamp also reveals their extreme worry about Reynolds's safety and well-being, with Hubachek doing all he could through American and Allied diplomatic channels to get her home and Duchamp continuing to try to persuade her to leave Paris and join him in North America. It is curious that both of these men continued to worry and try to take care of Reynolds when she was clearly doing a good job of it herself and for many others as well. She was neither in any immediate danger nor in a situation that she was unable to handle. Her gentle demeanor led friends and loved ones in the United States to doubt her ability to cope with the crises of war. Outwardly gentle, perhaps, but Mary Reynolds was a woman of strength, character, and determination. Her Résistance activities illustrate this, as does the fact that she was able to get herself out of Nazi-occupied France on her own, without help from either her brother or her lover.

By late summer 1942, it became apparent that Reynolds and her collaborators in the Résistance had been under Gestapo observation for some time. According to Brookes Hubachek, in the months prior to her escape, at least six of her compatriots were caught and killed. Reynolds just missed this same fate. "She left her home dressed in ordinary streetwear and went across the street to a French residence where, an hour later, she saw two carloads of armed German Gestapo surround her house."[45]

Escape

In September 1942, Reynolds illegally crossed the Line of Occupation and surreptitiously made her way alone to Lyons.[46] There she would wait, living anxiously in a small, mean room for eight weeks, for receipt of an exit visa and the other papers needed before she could continue her dangerous journey. Her most difficult task was to locate a guide who would agree to take her across the border to Spain. A month earlier, the Nazis had tightened their grip on France, shooting any guides caught taking Jews across the border and detaining and threatening others suspected of helping refugees. Reynolds stood out in any crowd. Although she spoke French fluently, she had an American accent. She was repeatedly warned not to speak or risk bringing unwanted attention her way. She quietly continued her negotiations with "passeurs," but was not successful in locating anyone willing to take on such a risk.

In mid-November, the Nazis marched into Lyons on their way to Marseilles. Shortly after their arrival, Reynolds went with her American passport to the Spanish consulate, where she was able to bribe a Spanish official and received a visa in only one day. On November 25, she was visited by the police and realized that she would have to leave immediately.[47] The following day, Reynolds left for Pau where she hoped to arrange to cross the Pyrenees by freight car. Unfortunately, the railway workers who had so heroically been smuggling refugees across the border, had recently been rounded up and sent to concentration camps, foiling this method of escape. Reynolds's only option appeared to be one that she had hoped to avoid: walking across the Pyrenees into Spain. Many of the passes were higher than those in the Alps; the route was fraught with danger from both border patrols and the elements.

After weeks of searching, Reynolds finally located a guide willing to take her across the border for thirty-five thousand francs. Initially, she turned the offer down as being too expensive, but rushed back when she learned that the Gestapo had again found her and left a message with her landlady demanding her appearance at the Kommissäriat the following morning. Her traveling companions were two Jewish men, a boy, and a mountain guide. They traveled light, carrying only their essentials. In addition, Reynolds carried a roll of paintings by her friend Man Ray. Prior to leaving for America, he had entrusted her with some of his paintings and books for safekeeping during the conflict. When fleeing Paris, Reynolds had hurriedly gathered a few of the unframed paintings in the hope of being able to return them to the artist, who was in California.[48]

The journey contrasted magnificent views with an arduous physical challenge. Walking heel to toe up ravines and over swollen gullies, the group endured extreme heat at the lower altitudes and sleet storms at the higher elevations. The physical exertion in the thin mountain air slowed their progress. On the eve of the third day, the party joyously reached the Spanish border. Their celebrating was short-lived, however. Two of the refugees were apprehended by the local police and arrested. Reynolds was the only one with proper papers, which in itself aroused suspicion. She was detained with the rest of the group and held six days for questioning. In the end, Reynolds was released, but not allowed to leave because the town of Canfranc, not Isaba, where she was, had been put on her passport as the Spanish port of entry. In order for her to leave, she needed to have the Canfranc stamp. Reynolds's American money and Banque de France draft were of no value to her in Isaba; with no ready currency to use for bribes or travel, she was stranded. Fortuitously, an anonymous Spanish gentleman sought her out in her hotel and secretly offered her the loan she needed, asking in return only that she post a love letter to his fiancée in Brazil. When Reynolds attempted to give him her greatest treasure—her wedding band—as collateral, he gallantly refused.

On December 14, 1942 Reynolds joyously cabled her brother of her arrival in Madrid. In his euphoric letter to Duchamp relaying this news, Hubachek wrote, "The cable from Madrid was like getting her back from the dead."[49] Acting upon a suggestion from the U.S. State Department, Hubachek had earlier prepaid Reynolds's fare of $942.90 to cover passage on Pan-American Airways' Yankee Clipper.[50] On the morning of December 31, he received another cable: "Awaiting plane probably January sixth. Love to all and Happy New Year."[51]

On January 6, 1943, Mary Reynolds boarded the aircraft bound for New York. She arrived with a badly infected leg from a wound sustained during a fall on her walk through the mountains, but her spirits were soaring. The Office of Strategic Services (O.S.S.), the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency, debriefed her at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, where she stayed until she regained her strength. Reynolds was glad of the opportunity to detail some of the Résistance activities, as well as confirm Nazi border guard locations. She also protested the lack of discretion of some of the radio broadcasts heard in the Occupied Zone that mentioned people by name, gave locations of Résistance activities, and generally threatened the effectiveness of the Résistance and the safety of those involved.

Next > Next >

Page 3 of 4

Warm Ashes: The Life and Career of Mary Reynolds

OTHER ESSAYS

Mary Reynolds: From Paris to Chicago to the Web

Documents of Dada and Surrealism:

Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

Hans Bellmer in The Art Institute of Chicago:

The Wandering Libido and the Hysterical Body

Essays | Works of Art | Book Bindings | Related Sites | Finding Aid | Search Collection

|

|