-

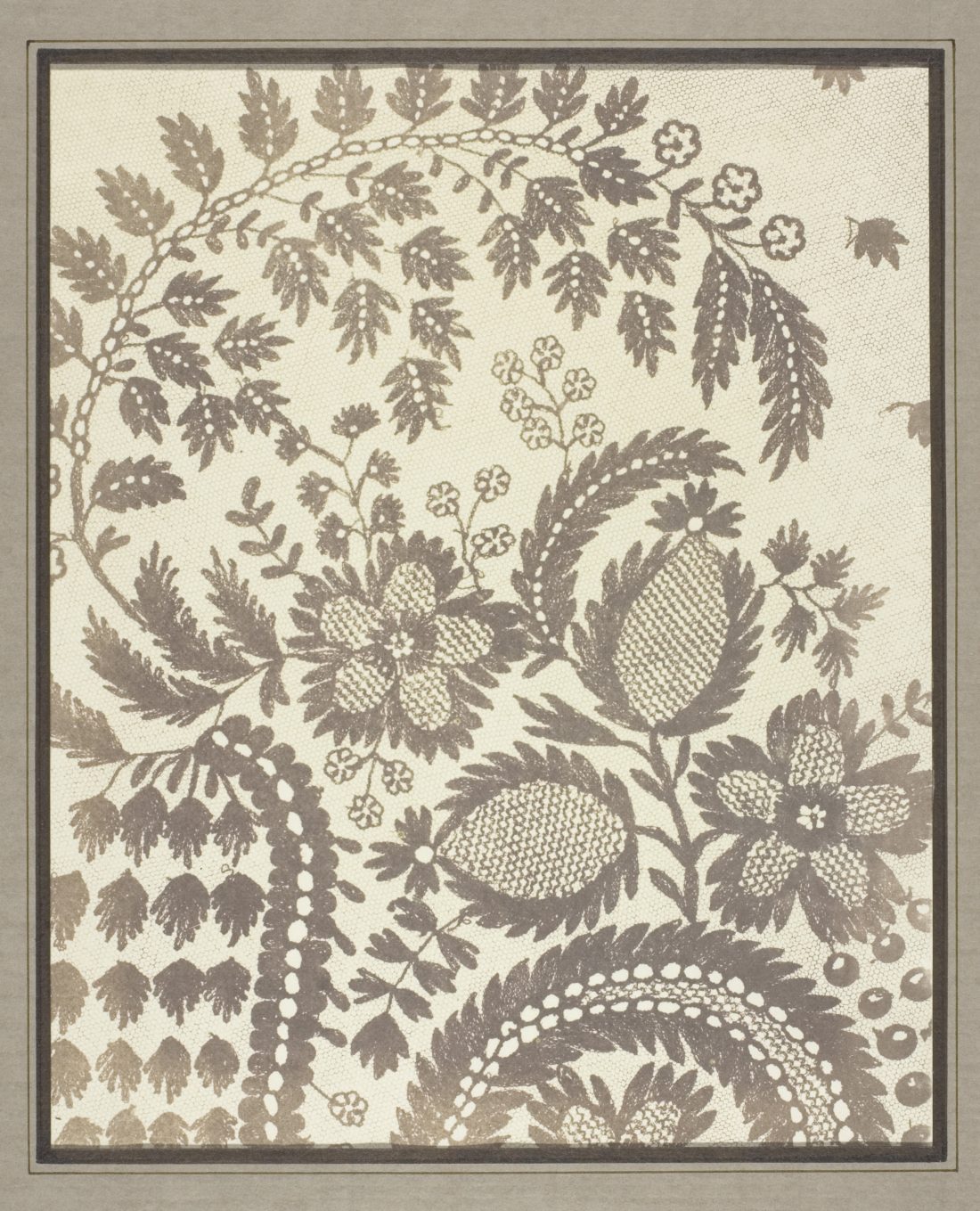

William Henry Fox Talbot, Lace, 1844/45

William Henry Fox Talbot, Lace, 1844/45 -

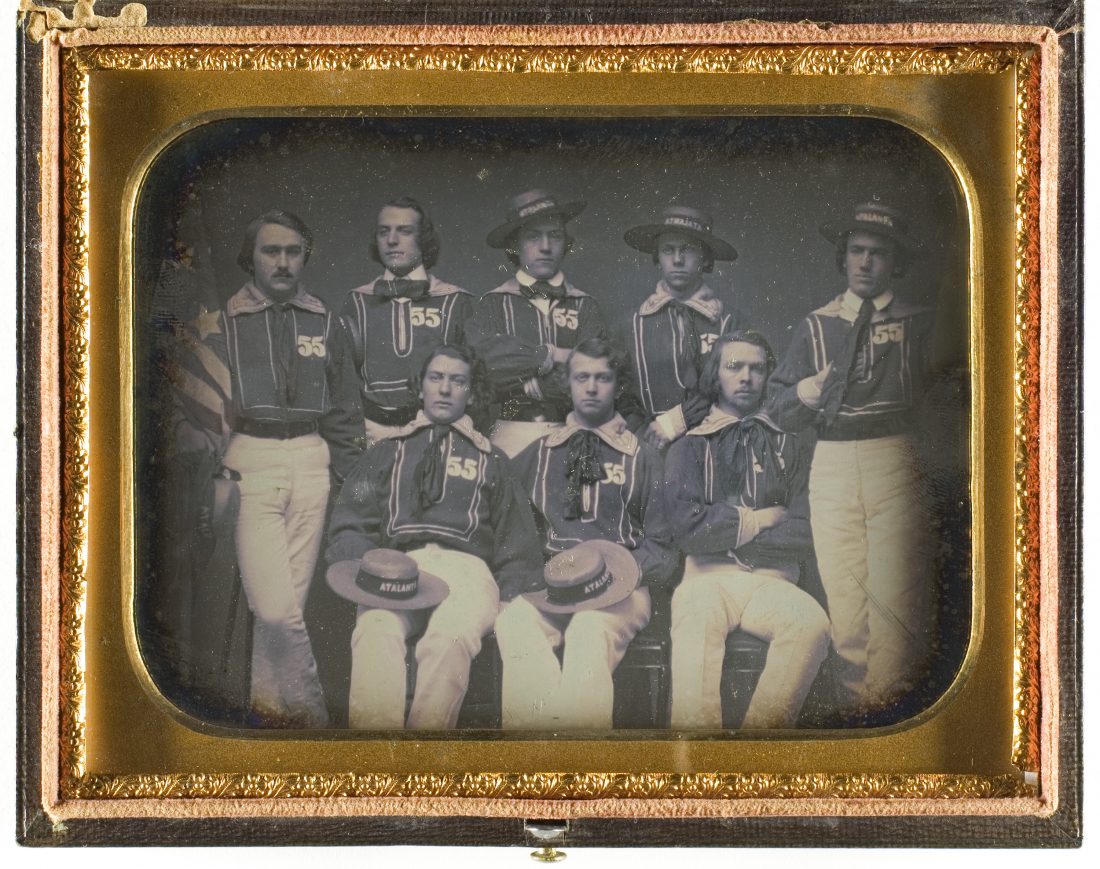

Artist unknown, Untitled (Eight Atalanta Crewmen), July 30, 1856

Artist unknown, Untitled (Eight Atalanta Crewmen), July 30, 1856 -

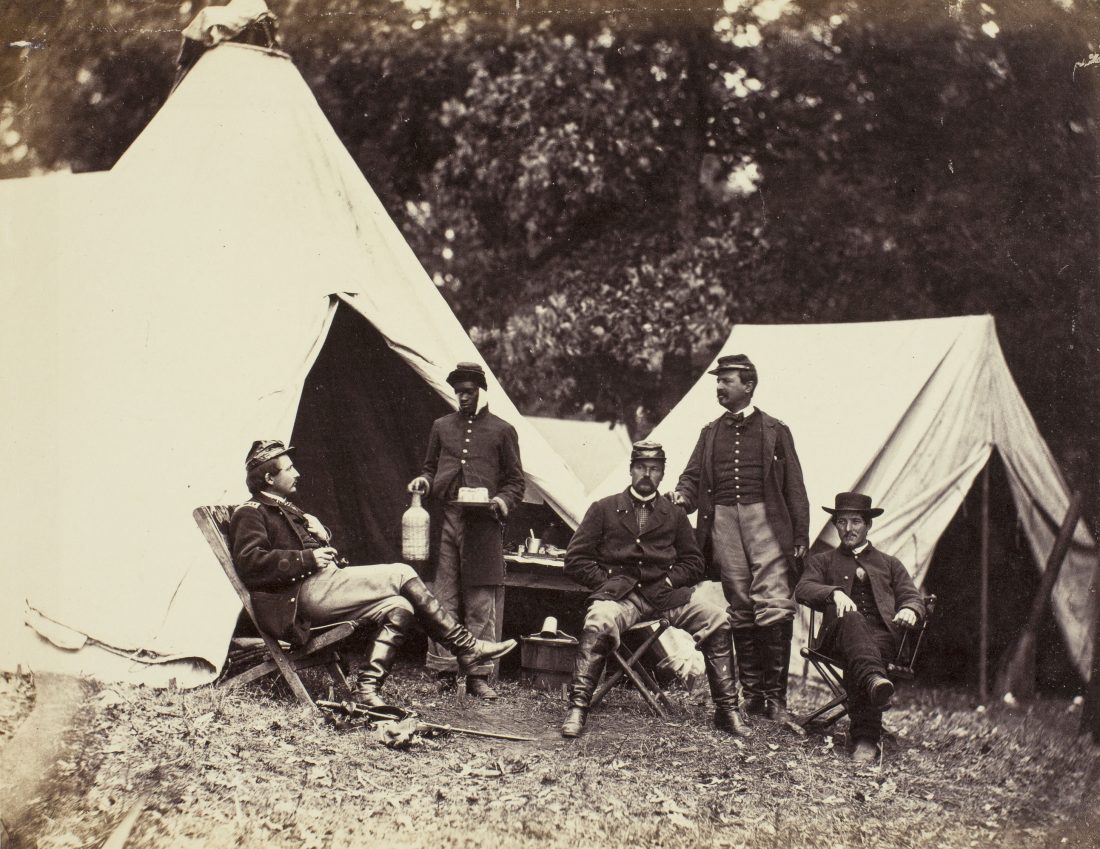

Alexander Gardner, What Do I Want, John Henry?, November 1862

Alexander Gardner, What Do I Want, John Henry?, November 1862 -

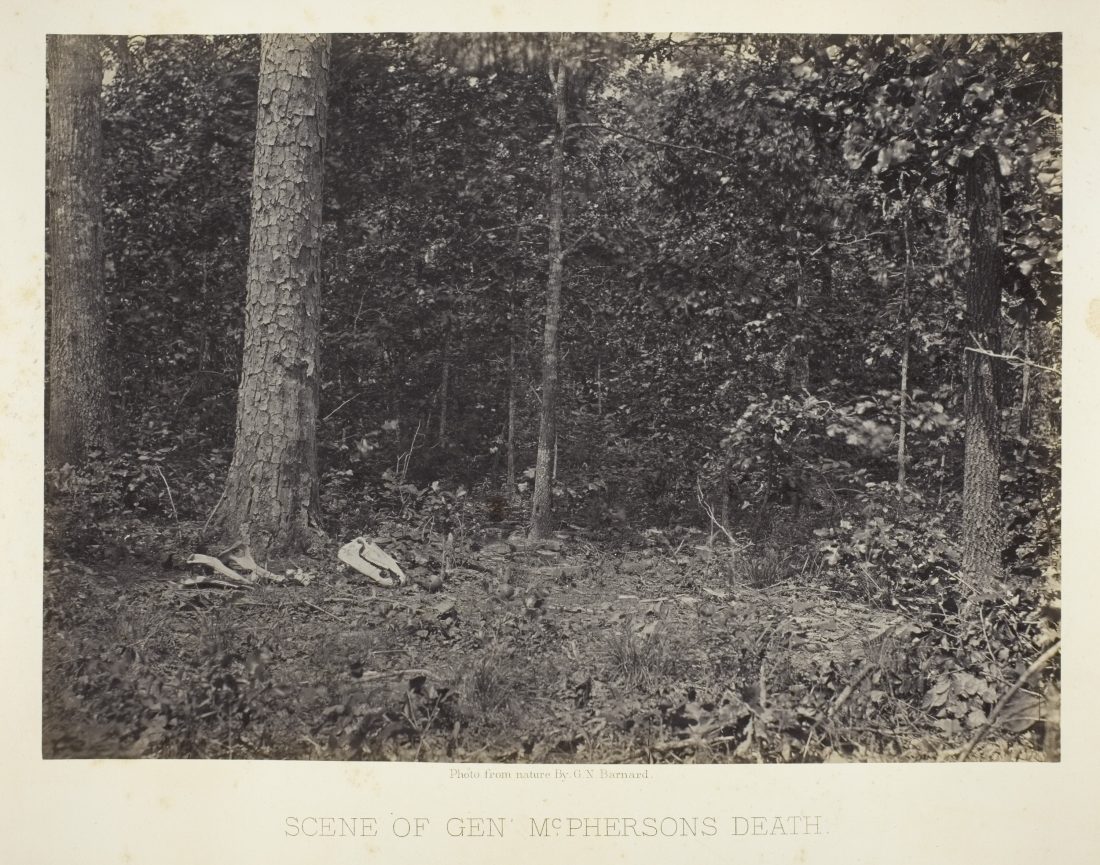

George N. Barnard, Scene of Gen. McPhersons Death, 1864/66

George N. Barnard, Scene of Gen. McPhersons Death, 1864/66 -

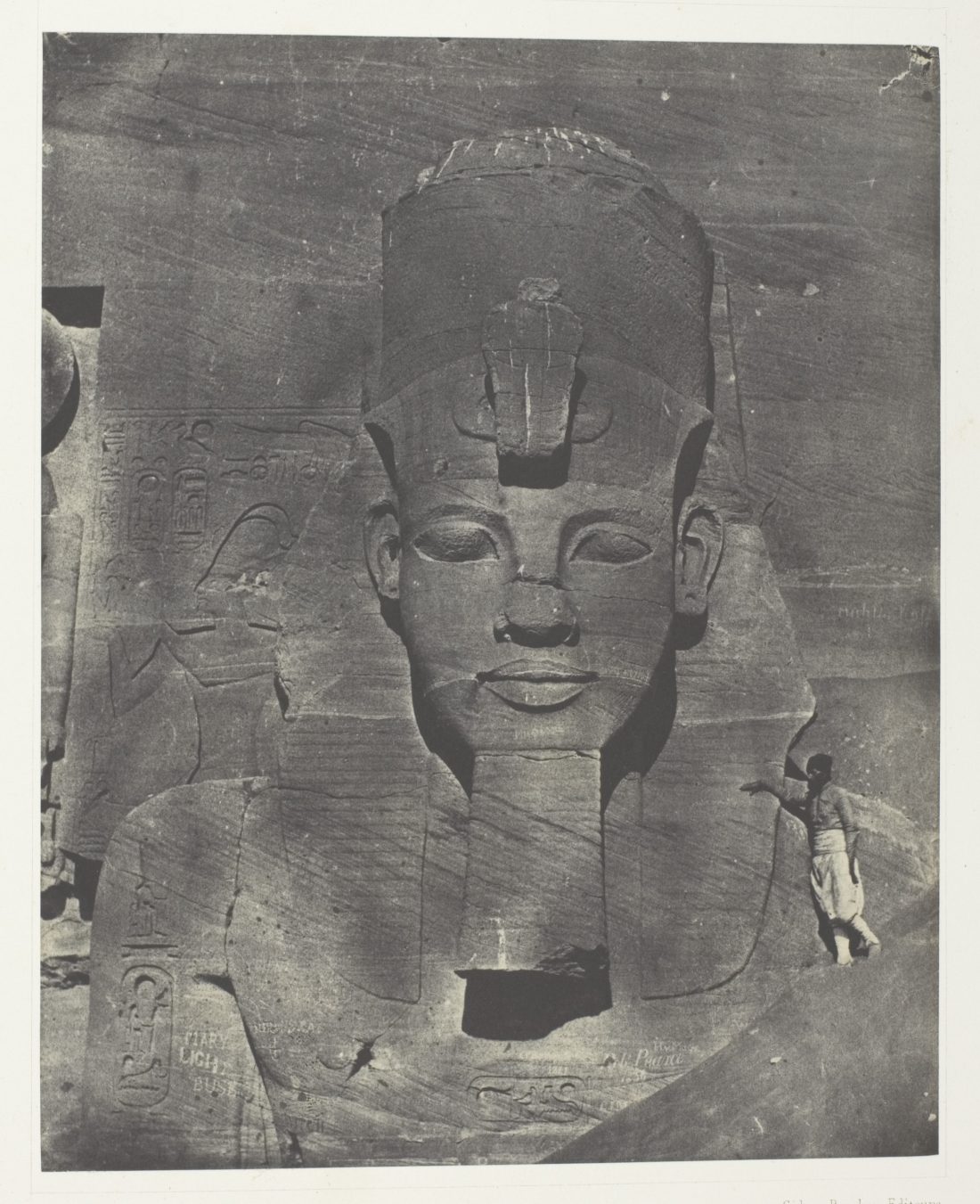

Maxime Du Camp, Ibsamboul, Colosse Médial (Enfoui) du Spéos de Phrè Nubie, Palestine et Syrie, 1849/51

Maxime Du Camp, Ibsamboul, Colosse Médial (Enfoui) du Spéos de Phrè Nubie, Palestine et Syrie, 1849/51 -

Francis Frith, Crocodile on a Sand-Bank, 1857

Francis Frith, Crocodile on a Sand-Bank, 1857 -

Julia Margaret Cameron, Julia Jackson, 1867

Julia Margaret Cameron, Julia Jackson, 1867 -

Peter Henry Emerson, A Stiff Pull, (Suffolk), 1883/87

Peter Henry Emerson, A Stiff Pull, (Suffolk), 1883/87 -

Roger Fenton, The Valley of the Shadow of Death, 1855

Roger Fenton, The Valley of the Shadow of Death, 1855 -

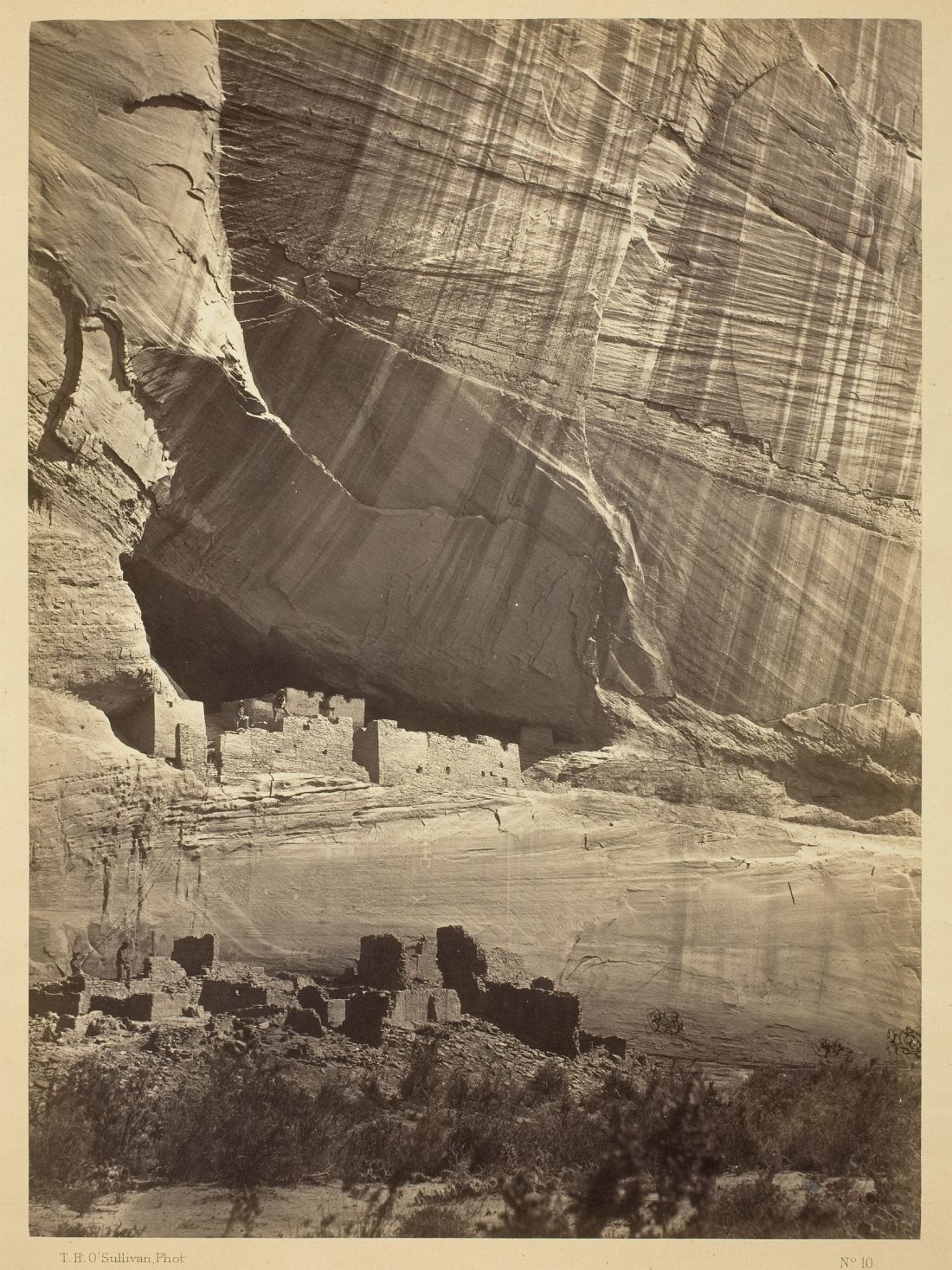

Timothy O’Sullivan, Ancient Ruins in the Cañon de Chelle, N.M. In a niche 50 feet above present Cañon bed., 1873

Timothy O’Sullivan, Ancient Ruins in the Cañon de Chelle, N.M. In a niche 50 feet above present Cañon bed., 1873

The Nineteenth Century

In a 1963 article for Contemporary Photographer, Hugh Edwards explained that his exhibition goals went beyond presenting monographic shows of new work: “My intention was also to exhibit each year at least two photographers of the past, for it is just short of amazing how little is known—and by photographers—of masters like Fox Talbot, David Octavius Hill, Roger Fenton, Peter Henry Emerson, Alexander Gardner, George M. Barnard, and countless others.”[1] In this stated commitment to photographic precedents, particularly work of the nineteenth century, Edwards was rare—if not unique—among his American peers. Although exhibitions of nineteenth-century photography ultimately fell short of his semiannual goal, in his prescient acquisitions Edwards had a permanent impact on the Art Institute’s photography collection.

The first exhibition Edwards mounted as curator of photography was Masterpieces of Photography from the Museum’s Collection (September 18–November 8, 1959). Organized before he was able to add substantially to the museum’s holdings, the exhibition nevertheless showcased key prints by nineteenth-century practitioners Julia Margaret Cameron and David Octavius Hill, whose works formed part of the Alfred Stieglitz Collection (gifted to the museum in 1949); Francis Frith’s views of Egypt; and a handful of American daguerreotypes and tintypes. This exhibition set the stage for Edwards’s ideal program of interspersing living masters with, as the brochure put it, “photographers of the past who have contributed to the traditions of photographic esthetics, and who demonstrate that photography may be a sincere and permanent vehicle for human expression.”[2] In the following years the curator presented exhibitions on Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War (also 1959), Adam Clark Vroman (1962), Thomas Eakins (1970), and a group show from the collection focusing on photography before 1914 (1968).

At a moment before the establishment of a market for fine art photography, Edwards’s enthusiasm for the medium’s early years was shared by only a handful of curators, collectors, and rare-book dealers. Beaumont Newhall, the founding curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art who was then the director of the George Eastman House, served as Edwards’s primary ally in this endeavor. Newhall wrote to the French collector André Jammes in 1959, “We are delighted that the Art Institute—which, as you know, is one of the largest and finest art museums in the United States—has decided to build up an historical photograph collection, and we are assisting them by advice and duplicates.”[3] That year, Newhall offered to sell Edwards duplicative material from the Eastman House, and Edwards rushed to Rochester to make selections. In 1959 alone he acquired key albums of photographs by Maxime Du Camp, Peter Henry Emerson, Roger Fenton, Francis Frith, Timothy O’Sullivan and William H. Bell, and Andrew J. Russell, as well as a boxed set of O’Sullivan stereographs and assorted cased images by unknown makers. This acquisition accounted for an astonishing total of more than 400 works, including some of the most significant nineteenth-century photography of the American West and the Middle East. Newhall also generously brokered a deal for Edwards to acquire selections from Jammes—whose collection of nineteenth-century photography, already strong in 1959, would grow to become one of the most renowned in the world—but although Edwards secured the funds, Jammes decided in the end not to sell. Anticipating success, Newhall had written to Edwards, “With what you are getting you will have the best collection of 19th century things next to us.”[4]

Throughout his tenure Edwards continued to add to the museum’s holdings in historical photography. He acquired a salted paper print by David Octavius Hill and a paper negative by Charles Nègre from the antiquarian bookseller Ernst Weil; albumen prints by Julia Margaret Cameron from the Chicago rare-book dealers Hamill and Barker; an album of Paris by Charles Soulier along with a copy of George Barnard’s 1866 Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign, inscribed by General William Tecumseh Sherman, from the antique dealer Leonard Balish; and groups of William Henry Fox Talbot prints from the West Coast rare-book dealer David Magee and from the photographer’s descendants. He wrote excitedly to Ansel Adams about his success at a 1967 auction at Parke-Bernet Galleries in obtaining Roger Fenton portraits from the Crimean War, Alexander Gardner’s Sketch Book of the Civil War, and a pair of half-plate daguerreotypes.[5] And he continued a lengthy correspondence with Jammes, gaining advice and leads on items from his wish list. While pursuing some of the most important figures in nineteenth-century photography, Edwards also remained open to practices that would now be considered “vernacular,” acquiring several daguerreotypes from unknown makers and a few eclectic Victorian albums.

For photographers and students in the Chicago area, the Art Institute Print Study Room became the one place where they could learn the history of photography, taught informally by Edwards himself, who often brought out boxes of photographs for viewing.[6] In later years, Edwards formalized his teaching in a now-legendary history of photography class he led at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In the study room and his classes, Edwards connected the contemporary work about which he was so enthusiastic with a long, rich history of photographic antecedents.

Elizabeth Siegel, Curator of Photography

[1] Edwards, “Some Experiences with Photography,” Contemporary Photographer 4, 4 (Fall 1963), p. 7.

[2] Edwards, Masterpieces of Photography from the Museum’s Collection, exh. brochure (Art Institute of Chicago, 1959).

[3] Beaumont Newhall to André Jammes, Dec. 17, 1959, copy on file in the Photography Department, Art Institute of Chicago.

[4] Beaumont Newhall to Edwards, Dec. 17, 1959, on file in the Photography Department, Art Institute of Chicago.

[5] Edwards to Ansel Adams, June 6, 1967, Ansel Adams Archive, Center for Creative Photography, the University of Arizona.

[6] See, for example, the recollections by Joel Snyder and Charles Swedlund in the Media section of this website.

Citation: Elizabeth Siegel, “The Nineteenth Century,” in Hugh Edwards at the Art Institute of Chicago, 1959–1970 (Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), http://media.artic.edu/edwards/.

Selected Exhibitions

Masterpieces of Photography from the Museum’s Collection (1959)

Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War (1959)

Photographs by Adam Clark Vroman (1962)

Selected Writings

“Some Experiences with Photography,” Contemporary Photographer 4, 4 (Fall 1963), pp. 5–8

Selected Acquisitions

Daguerreotypes, Tintypes, and Ambrotypes