-

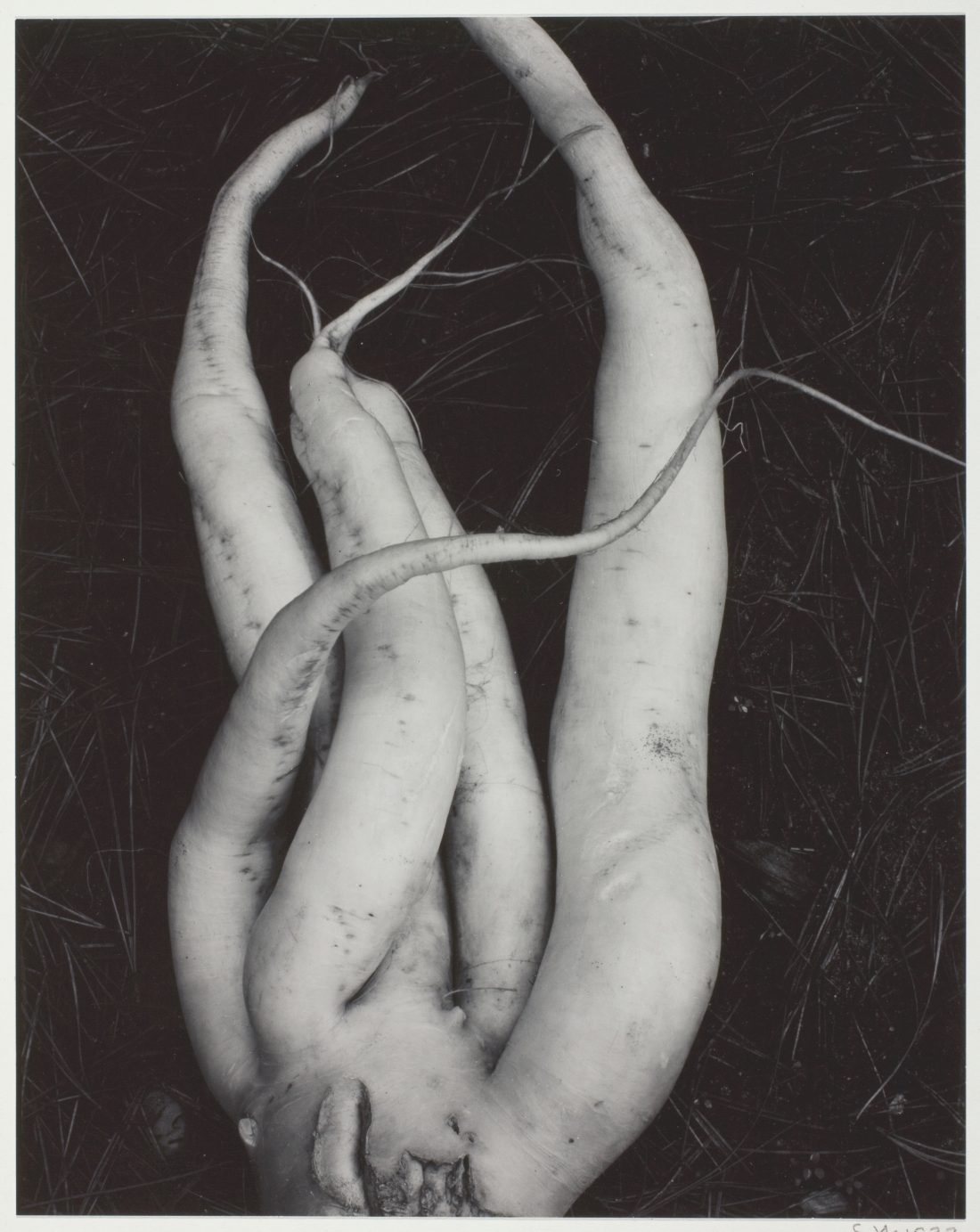

Edward Weston, White Radish, 1933. © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents and Edward Weston

Edward Weston, White Radish, 1933. © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents and Edward Weston -

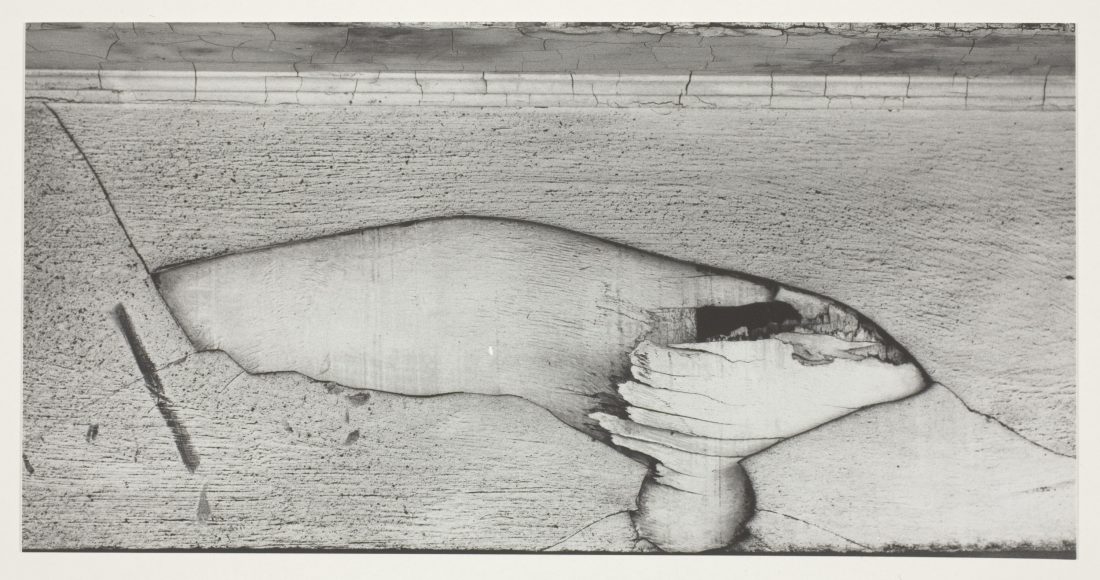

Minor White, Fillmore District, San Francisco, August 1959, printed 1959/60. Reproduced with permission of The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum. © Trustees of Princeton University

Minor White, Fillmore District, San Francisco, August 1959, printed 1959/60. Reproduced with permission of The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum. © Trustees of Princeton University -

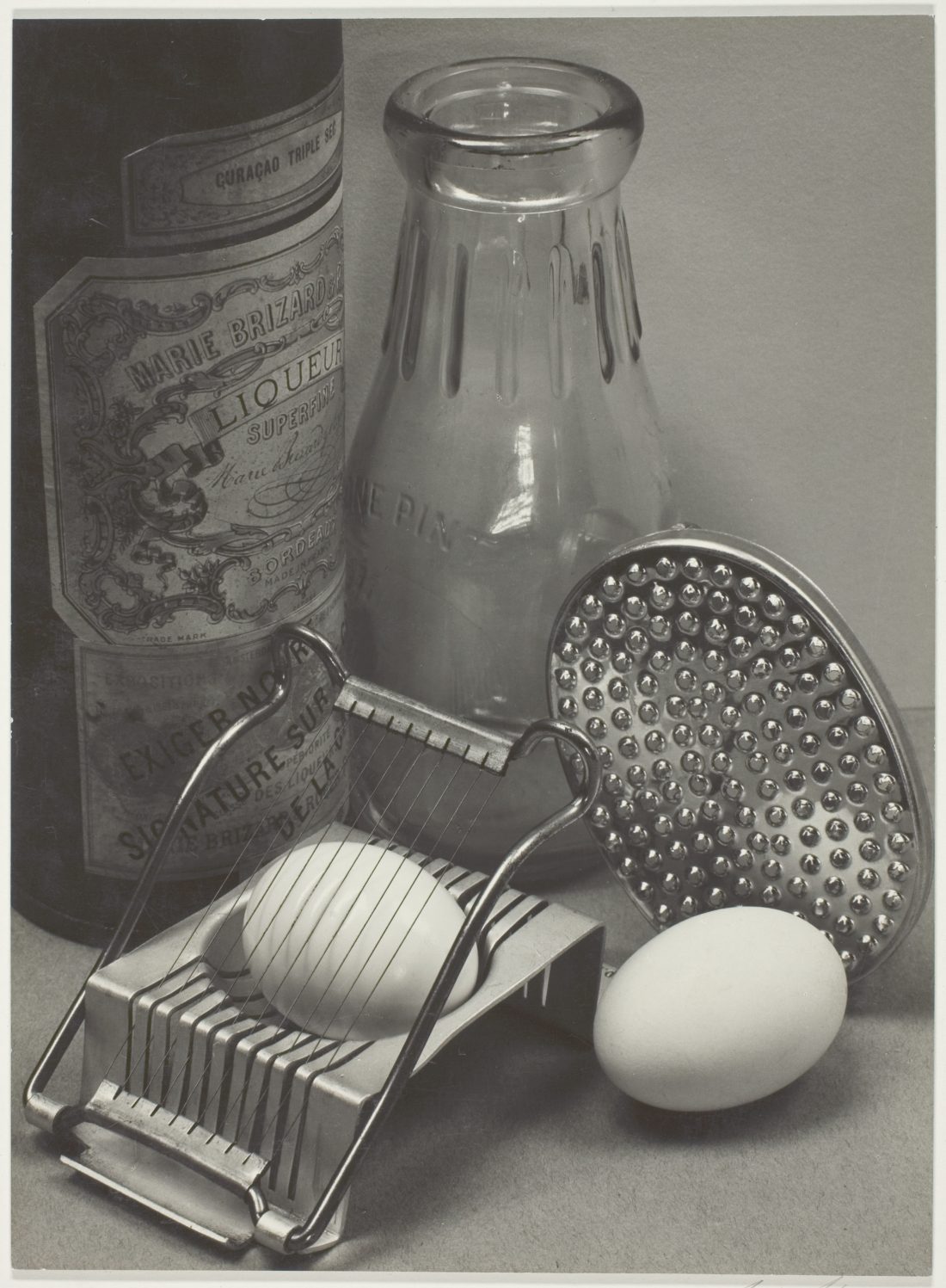

Ansel Adams, Still Life, San Francisco, California, c. 1932. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams, Still Life, San Francisco, California, c. 1932. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust -

Jean-Eugène-Auguste Atget, Versailles, Le Parc, 1901/02

Jean-Eugène-Auguste Atget, Versailles, Le Parc, 1901/02 -

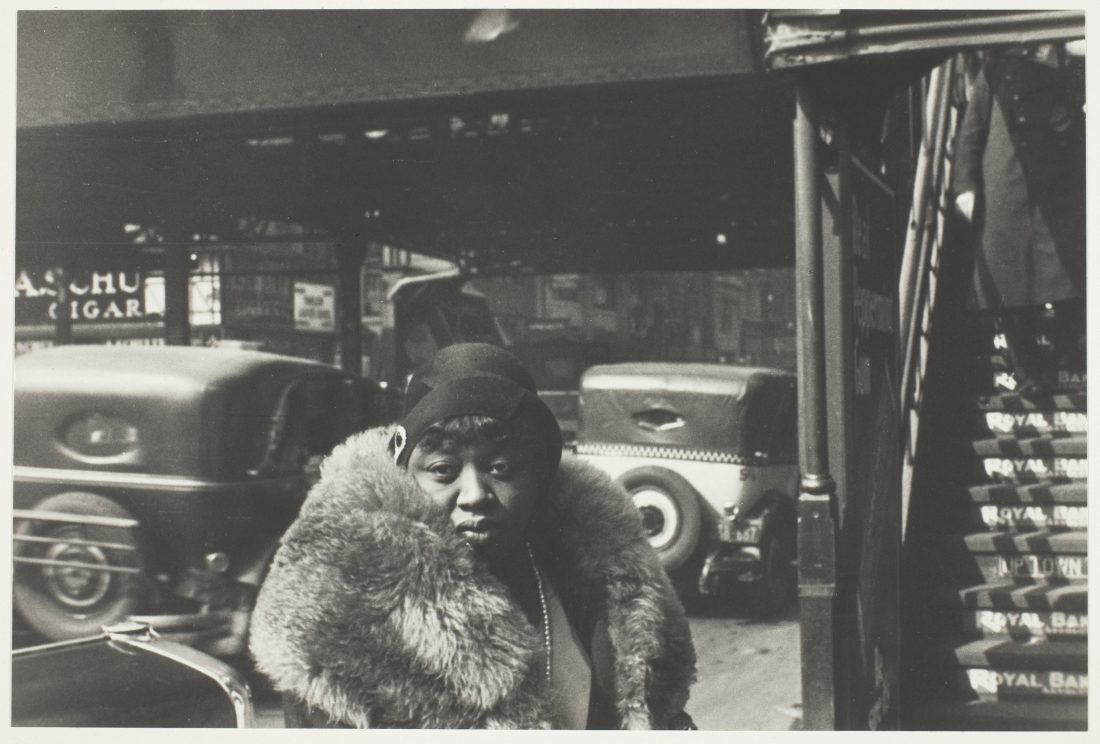

Walker Evans, 42nd Street, 1929, printed c. 1962. © Walker Evans Archive, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Walker Evans, 42nd Street, 1929, printed c. 1962. © Walker Evans Archive, the Metropolitan Museum of Art -

Lewis Wickes Hine, Sadie Pfeifer, a Cotton Mill Spinner, Lancaster, South Carolina, 1908

Lewis Wickes Hine, Sadie Pfeifer, a Cotton Mill Spinner, Lancaster, South Carolina, 1908 -

Inge Morath, Mrs. Eveleigh Nash and Chauffeur during Her Daily Outing in the Mall, London, 1953. © Magnum Photos, Inc. and the Inge Morath Foundation

Inge Morath, Mrs. Eveleigh Nash and Chauffeur during Her Daily Outing in the Mall, London, 1953. © Magnum Photos, Inc. and the Inge Morath Foundation -

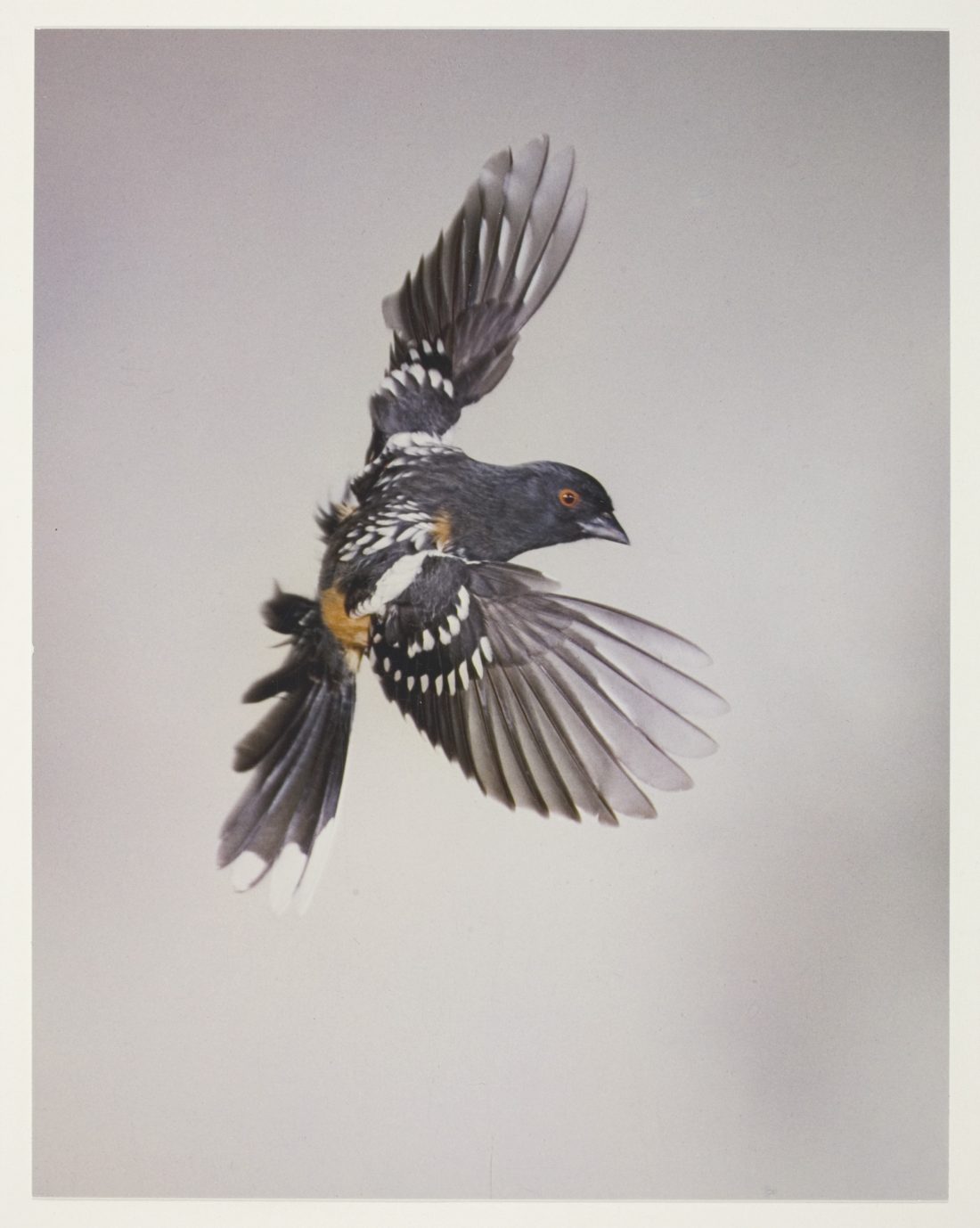

Eliot Porter, Spotted Towhee, 1941/64. © 1990, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

Eliot Porter, Spotted Towhee, 1941/64. © 1990, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas -

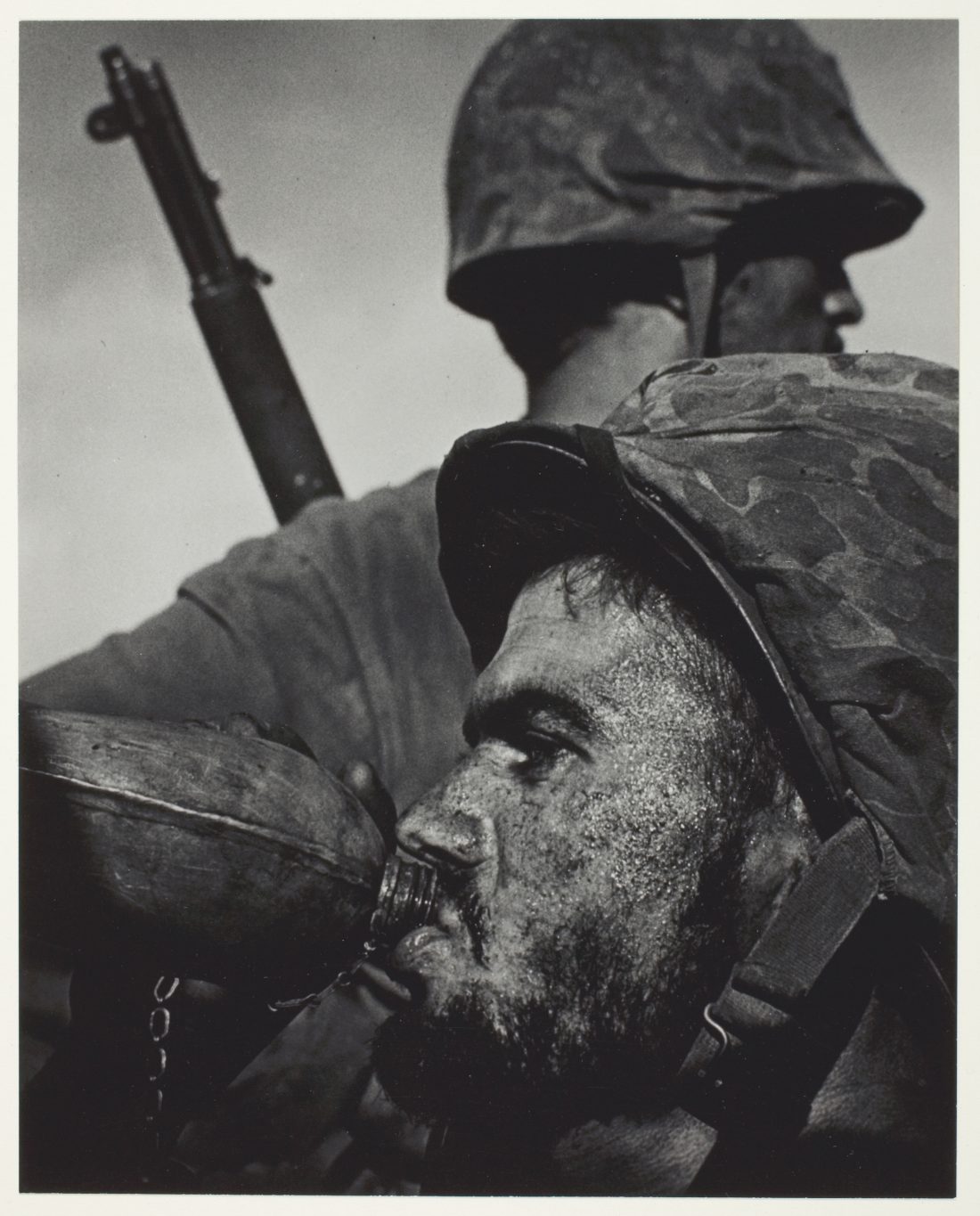

W. Eugene Smith, Marine Drinking, Battle for Saipan, June 1944. © Estate of W. Eugene Smith/Kevin Smith

W. Eugene Smith, Marine Drinking, Battle for Saipan, June 1944. © Estate of W. Eugene Smith/Kevin Smith -

Albert Renger-Patzsch, Oak Preserve in Wamel (Eichenkamp bei Wamei), 1945/46. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Germany

Albert Renger-Patzsch, Oak Preserve in Wamel (Eichenkamp bei Wamei), 1945/46. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Germany

Modern Classics

By the time Hugh Edwards became curator of photography in 1959, a nascent canon of photography was taking shape. Recent exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the San Francisco Museum of Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago, along with new monographs and survey books, had cemented the place of (mostly American) contemporary figures such as Ansel Adams, Berenice Abbott, Brassaï, Harry Callahan, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans, Imogen Cunningham, Dorothea Lange, Aaron Siskind, Paul Strand, and Edward Weston, among others. Edwards was determined to organize a program of acquisitions and exhibitions that showcased nineteenth-century practitioners along with younger, less familiar artists, but it would have been neither possible nor desirable to ignore those who had achieved success in the fledgling field of photography’s art history.

Edwards organized one-man exhibitions of Eugène Atget, George Platt Lynes, Eliot Porter, Weston, and Minor White, adding substantial groups of their work to the collection. He acquired a few key works by favorites Cartier-Bresson, Cunningham, and Albert Renger-Patzsch, as well as three Ansel Adams portfolios along with individual prints donated by the gallerist-turned-curator Katharine Kuh (Edwards maintained a lengthy correspondence with Adams). He also granted exhibitions to Dorothea Lange and Pirkle Jones, Frederick Sommer, and Aaron Siskind, adding work to the collection when possible.

Edwards was most enthusiastic, however, about what he identified as a particularly American tradition of realism that dated back to the daguerreotype. This lineage, he felt, continued through the early twentieth-century work of Lewis Hine and his near successor Walker Evans and found current expression in the photographs of W. Eugene Smith and the work of Robert Frank, still at the early stages of his career. “All of them,” he wrote in 1962, “are recorder-interpreters who transcend their time and subject matter so that their work is characterized by an enduring contemporaneity.”[1] Edwards sought out Hine’s unflinching images of immigrants and child laborers from the first decades of the twentieth century, eventually adding more than one hundred of his photographs to the museum’s holdings and mounting The Interpretive Photography of Lewis Hine, a 1961 exhibition of loans from the George Eastman House. In 1962 he was able to fulfill a desire sparked by Walker Evans’s 1938 book American Photographs, purchasing a career survey of thirty pictures selected by Evans himself. And although he never exhibited the work of Eugene Smith, he acquired prints from key series at various points in his tenure. These artists formed the cornerstone of Edwards’s personal canon and, to him, paved the way for a new generation of observant, socially empathetic photographers.

Elizabeth Siegel, Curator of Photography

[1] Edwards, review of Railroad Men, by Simpson Kalisher, Infinity: American Society of Magazine Photographers 11, 3 (Mar. 1962), p. 19.

Citation: Elizabeth Siegel, “Modern Classics,” in Hugh Edwards at the Art Institute of Chicago, 1959–1970 (Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), http://media.artic.edu/edwards/.

Selected Exhibitions

Sequence 13: Return to the Bud by Minor White (1960)

Photographs by Edward Weston (1960)

George Platt Lynes: Portraits, 1931–52 (1960)

The Interpretive Photography of Lewis Hine (1961)

Photographs by Frederick Sommer (1963)

Aaron Siskind: Photographs 1954–1961 (1964)

Selected Writings

Selected Acquisitions