Gelatin silver print

Gift of William Kistler, 1977.682

One of the greatest challenges involved in aerial photography was deciphering the resulting images, as familiar landscapes often appeared as abstract patterns. Steichen recognized the need to create an efficient system of interpretation, and he fought for adequate training programs throughout his active duty, as he later explained:

The success with which aerial photographs can be exploited is measured by the natural and trained ability of those concerned with their study of interpretation. The aerial photograph is in itself harmless and valueless. It enters into the category of “instruments of war” when it has disclosed the information written on the surface of the print. The average vertical aerial photographic print is upon first acquaintance as uninteresting and unimpressive a picture as can be imagined. Without considerable experience and study it is more difficult to read than a map, for it badly represents nature from an angle we do not know.[1]

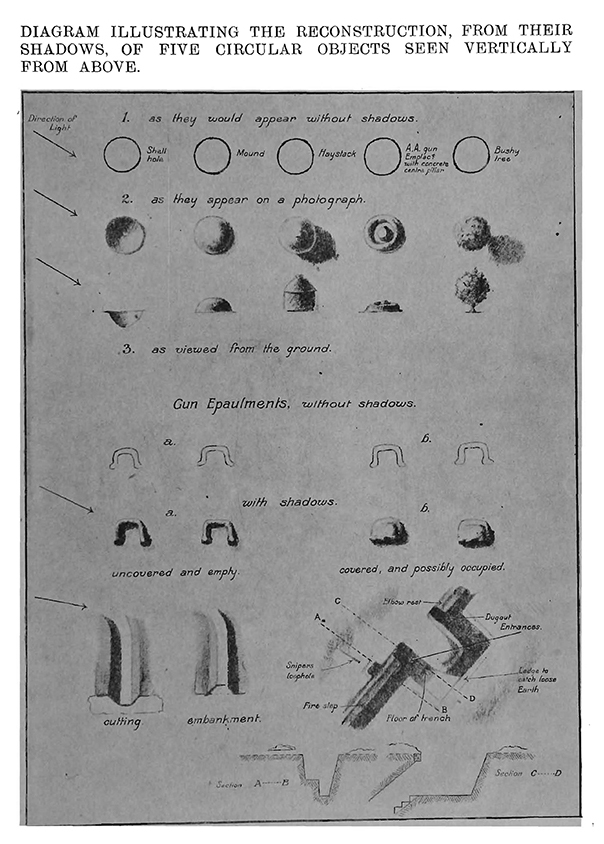

This diagram, from a 1917 book published by the army to aid the interpretation of aerial photography, shows how battlefield landmarks might appear from the air.

From Illustrations to Accompany Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs, Series A, 1917, pl. 2.

Inscribed recto, in negative, along bottom edge, in white: “9817. / U.S. 4 A.C. 90SQ 4 PHOTO. SEC. B510 N.W. LIMEY 363.9 – 234.9 25.8.18 13 H 3000M 52CM.”; inscribed recto, on album page, lower left, in black/brown ink: “German Front line Trenches was [crossed out] (St. Mihiel Sector) / dark zig-zag line, trenches and white edge to Trench is excavted [sic] earth. / (note trenches running through the woods)”; printed recto, on album page, lower right, in black ink: “Photographic Section. / Air Service. American Expeditionary Forces.”; inscribed recto, on album page, lower right, in blue ink “6”; unmarked verso

[1] Edward Steichen, “American Aerial Photography at the Front,” The Camera: The Magazine for Photographers (July 1919), p. 359.