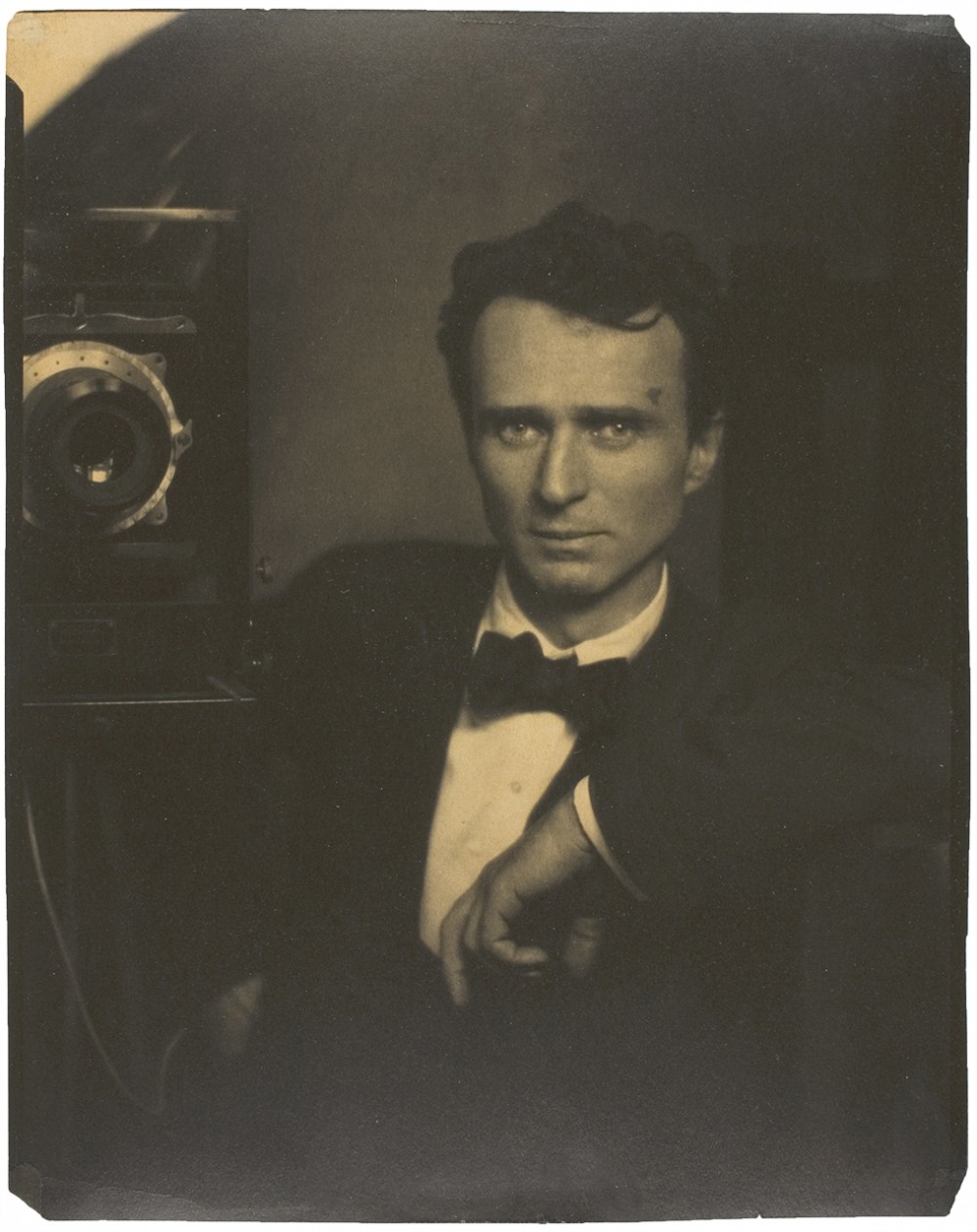

At the start of World War I, in 1914, Edward Steichen was a pioneering champion of fine-art photography—he had a leading reputation in the Photo-Secession movement in New York and had cofounded its trailblazing journal Camera Work. Yet by the early 1920s, Steichen had rejected the soft-focus, dreamy landscapes and portraits of his early years in favor of realist photographs made for informational purposes or popular consumption. This turning point was first signaled by Steichen’s role in World War I as chief of the Photographic Section of the American Expeditionary Forces and was fully realized in his subsequent work as lead photographer at Condé Nast Publications, from 1923 to 1937.

Author Archives: Ariel Pate

Outbreak of War, 1914–1917

Steichen, who had come to regard France as a second homeland, was quick to enlist once the U.S. officially entered the war in 1917. Though at 38 he was eight years older than the age limit set by the Signal Corps, his experience as a photographer made him a valuable recruit, and he entered active duty in July 1917 as a first lieutenant.

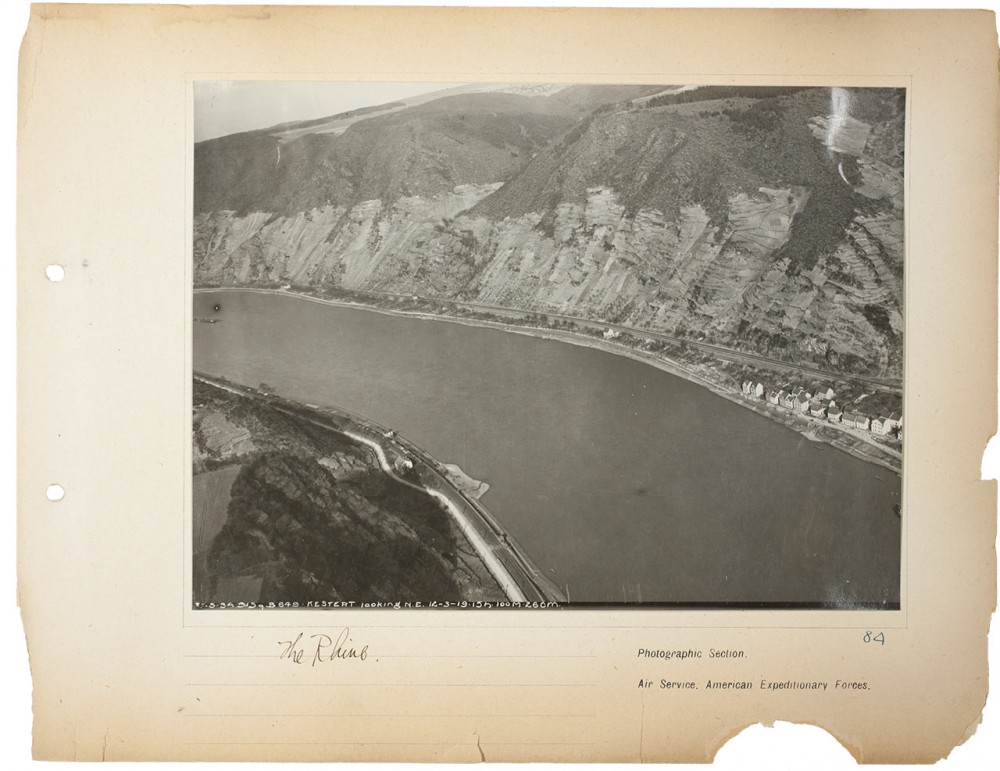

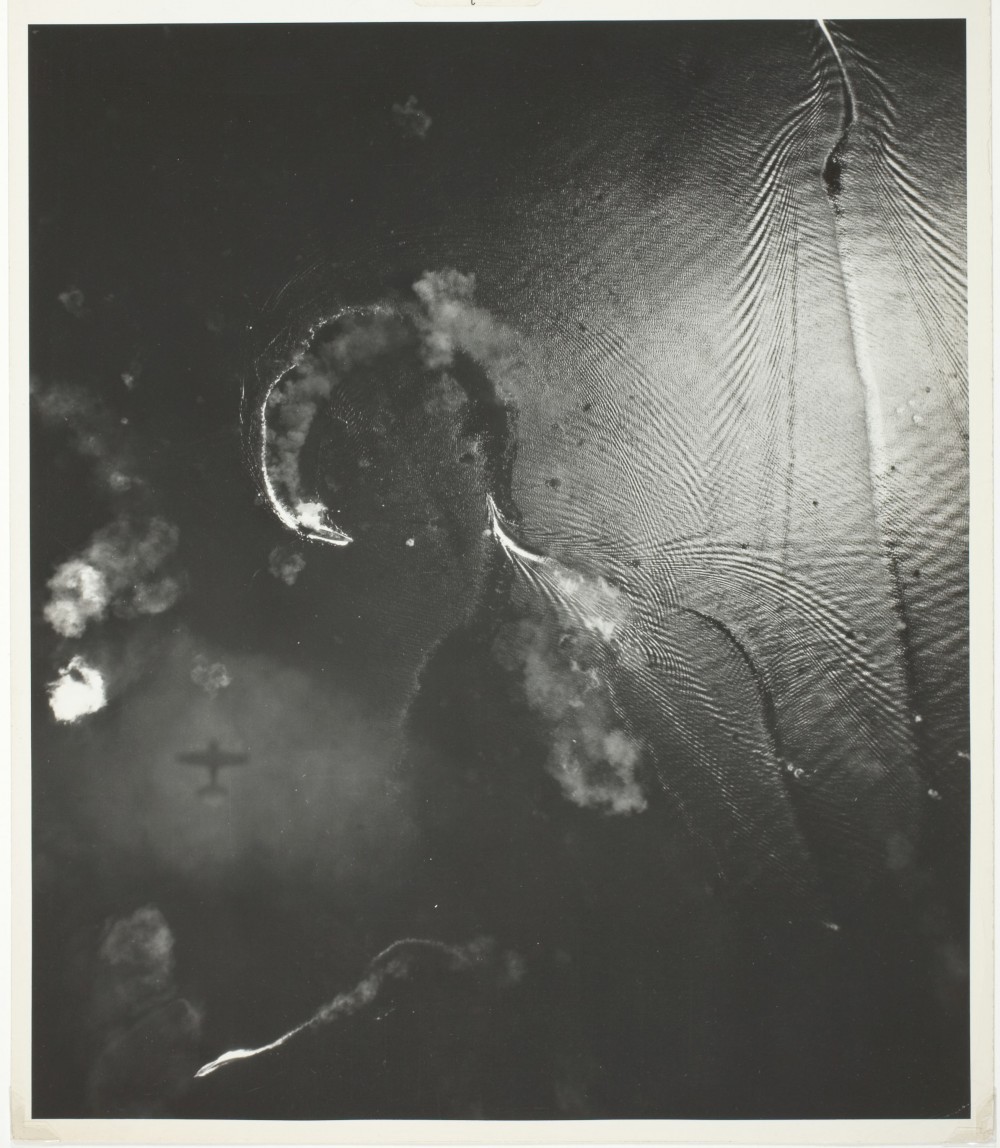

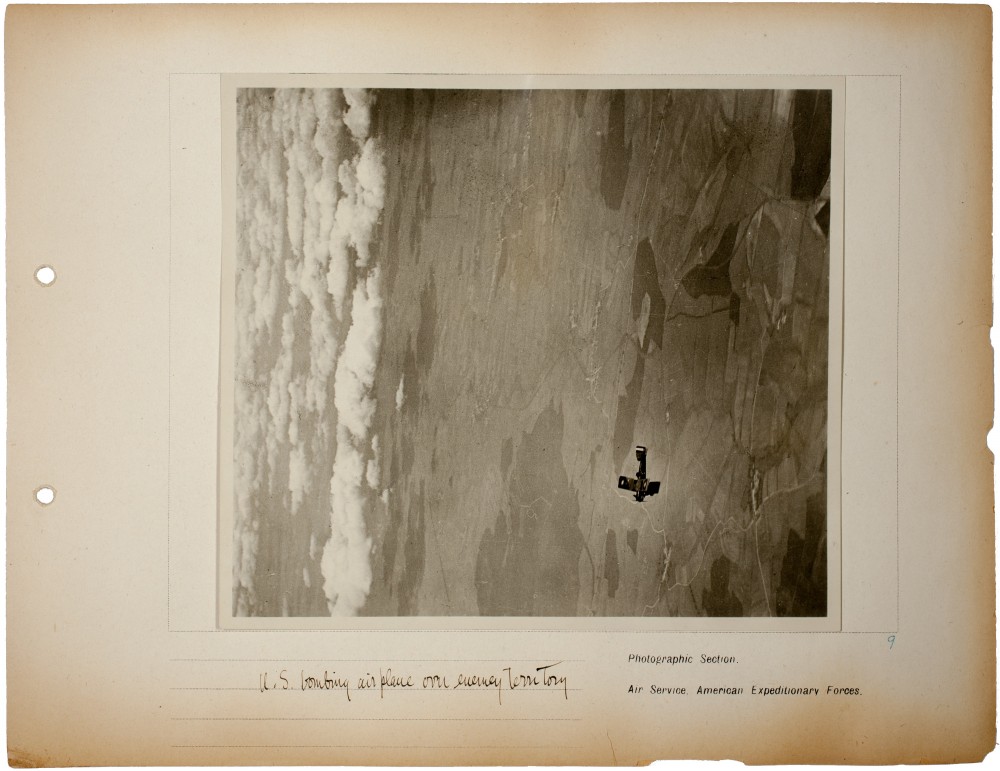

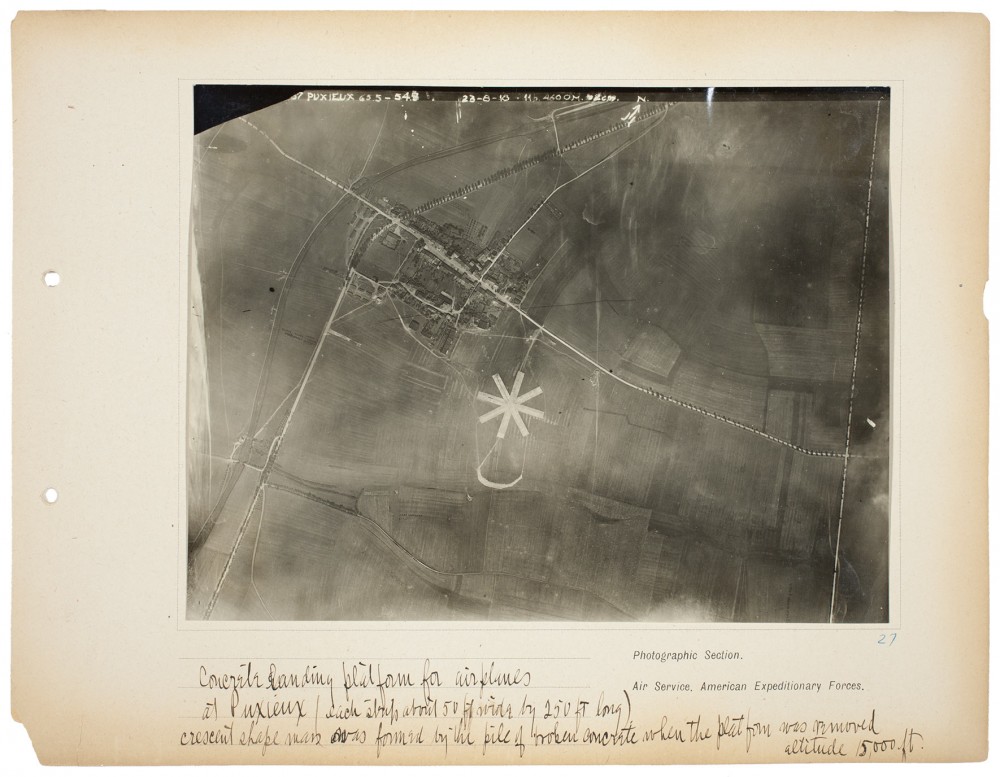

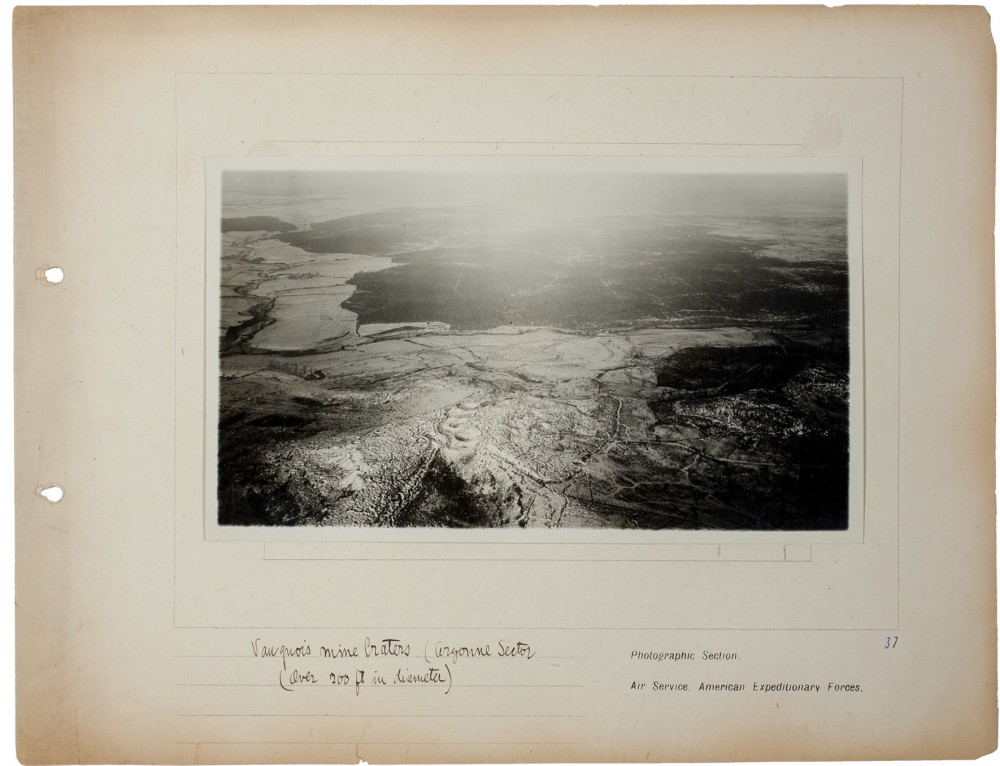

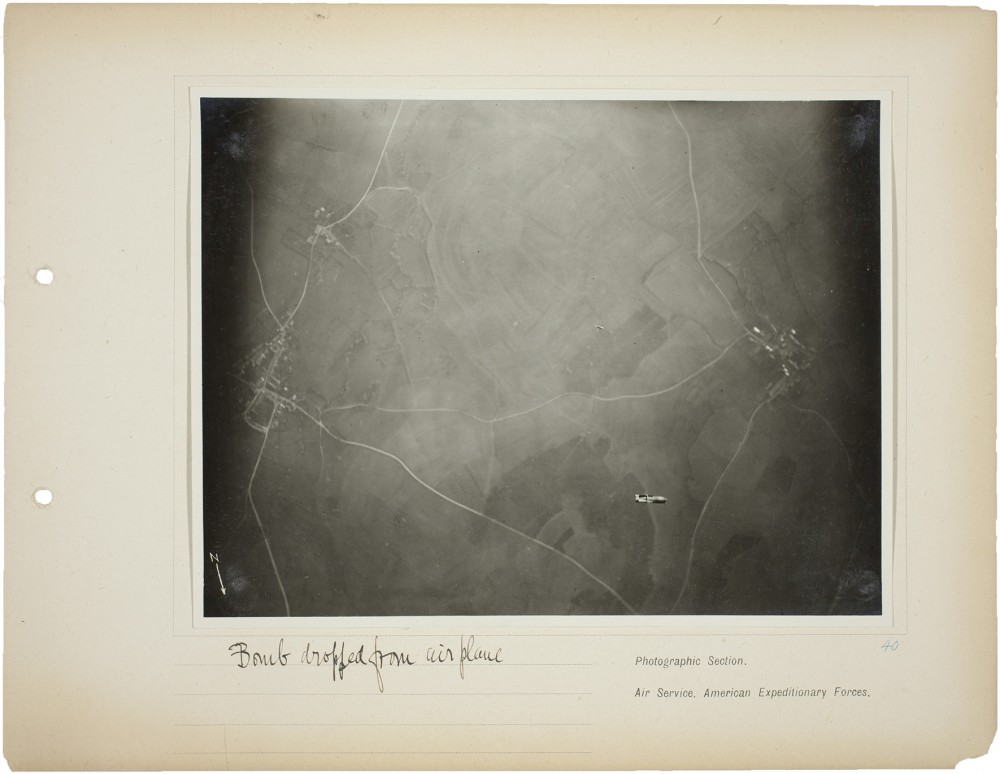

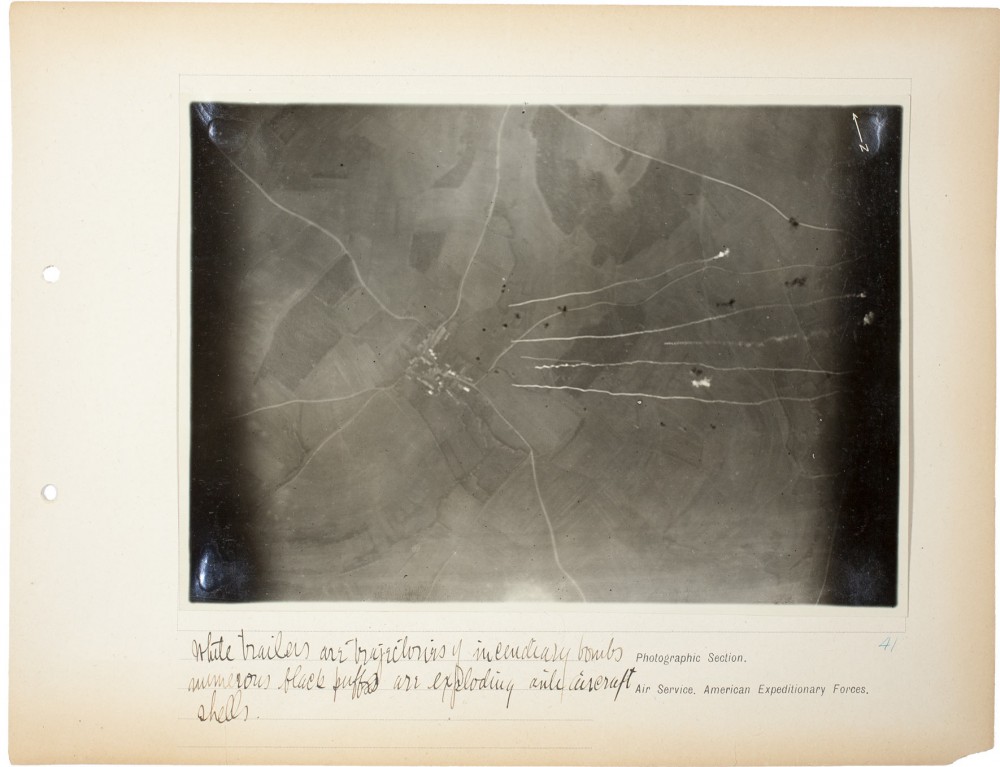

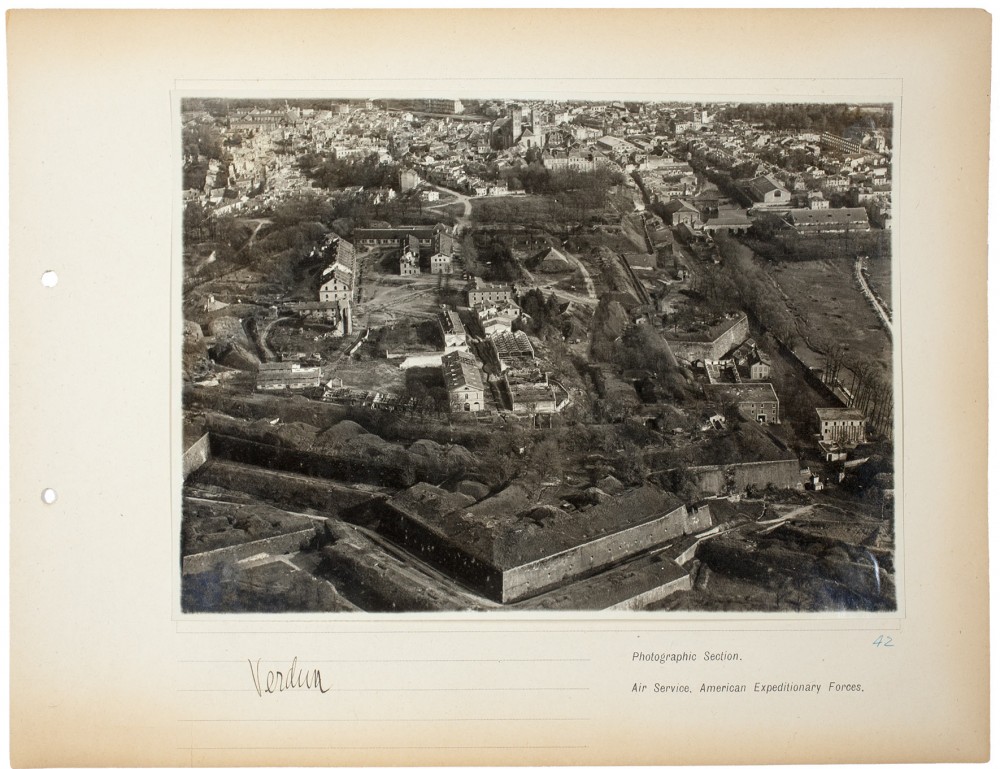

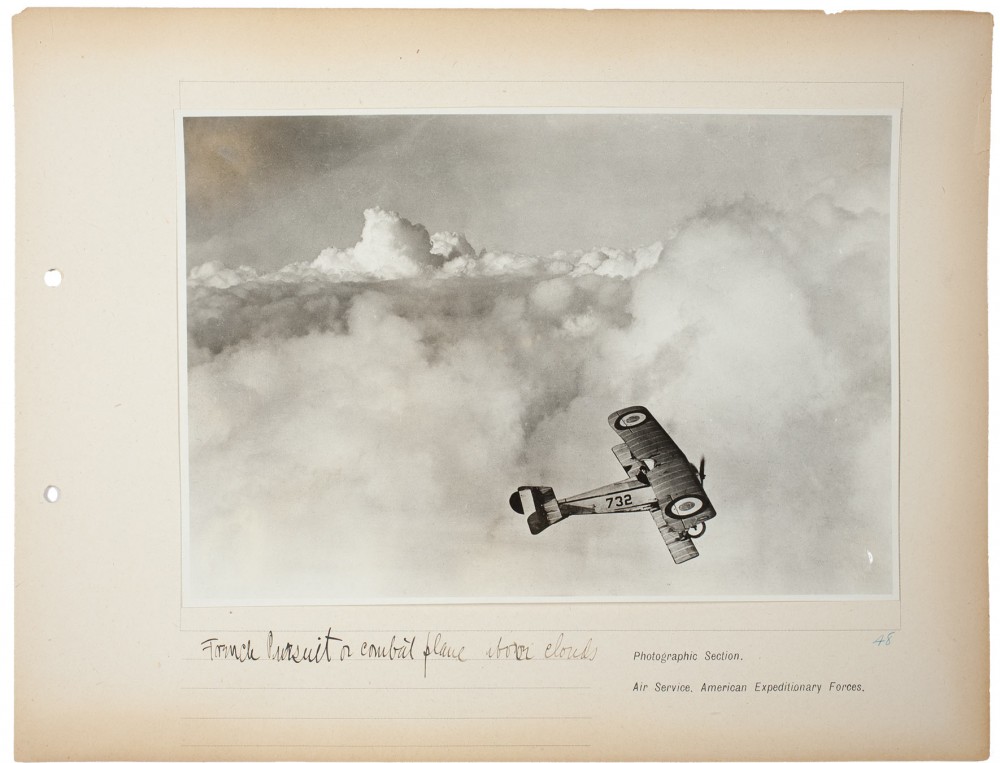

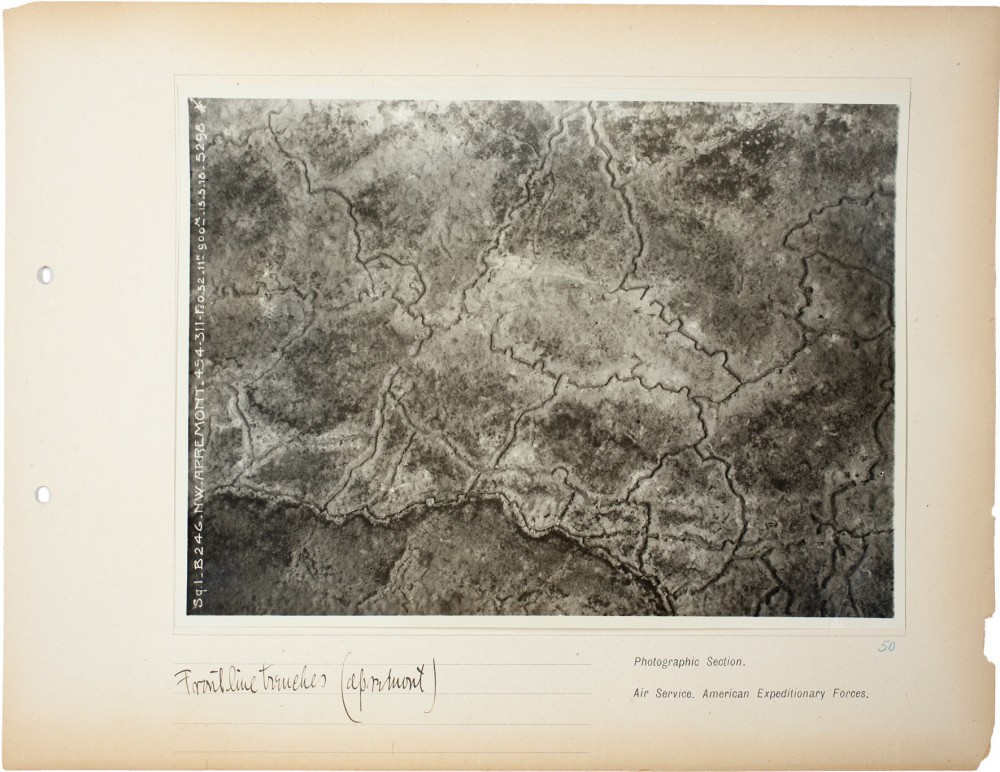

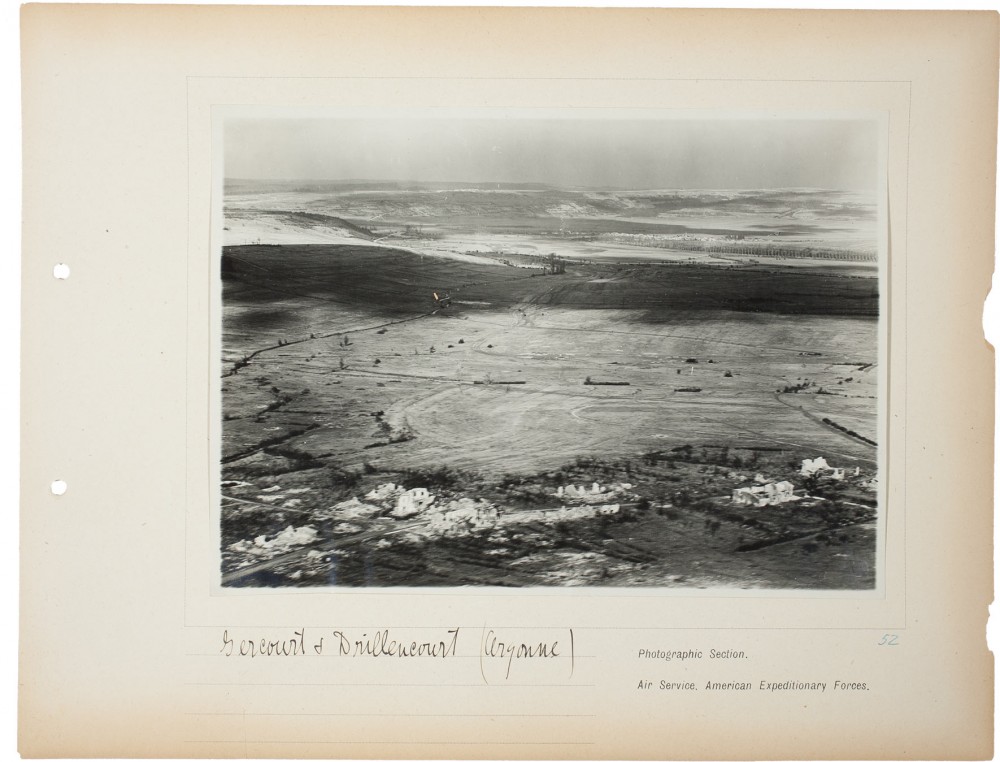

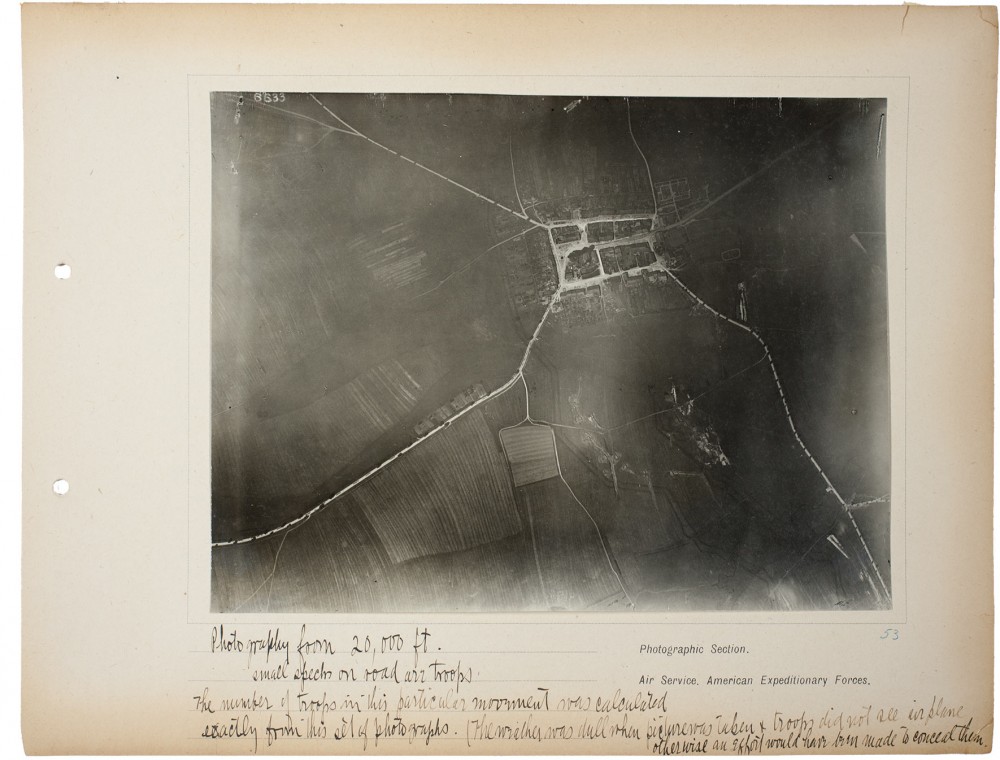

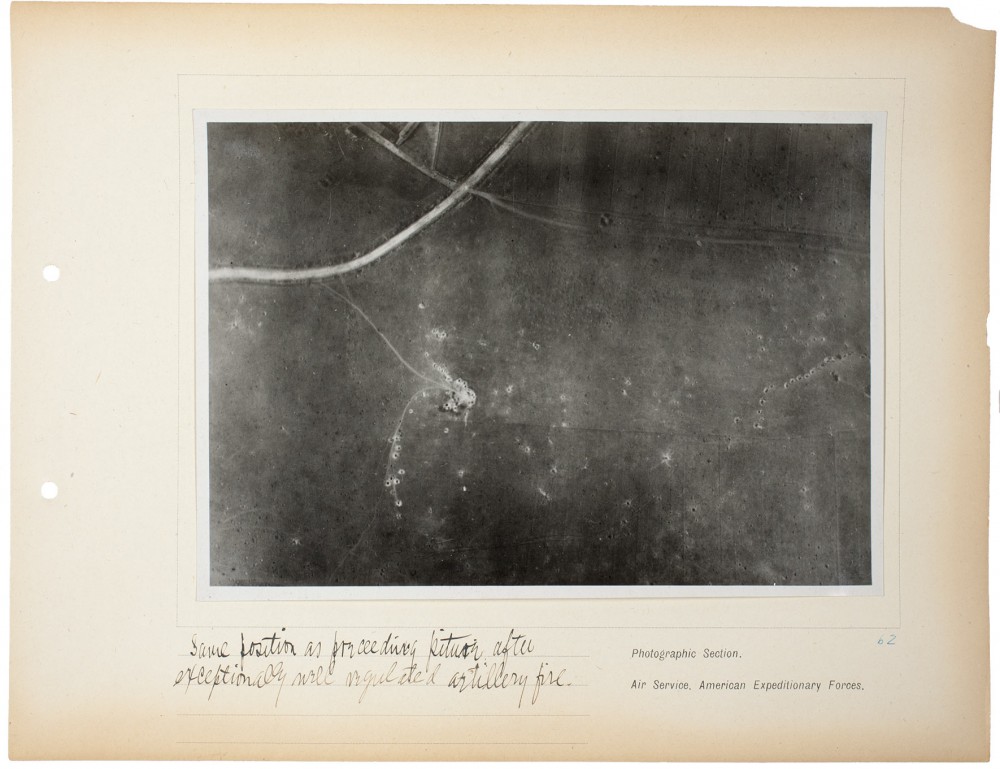

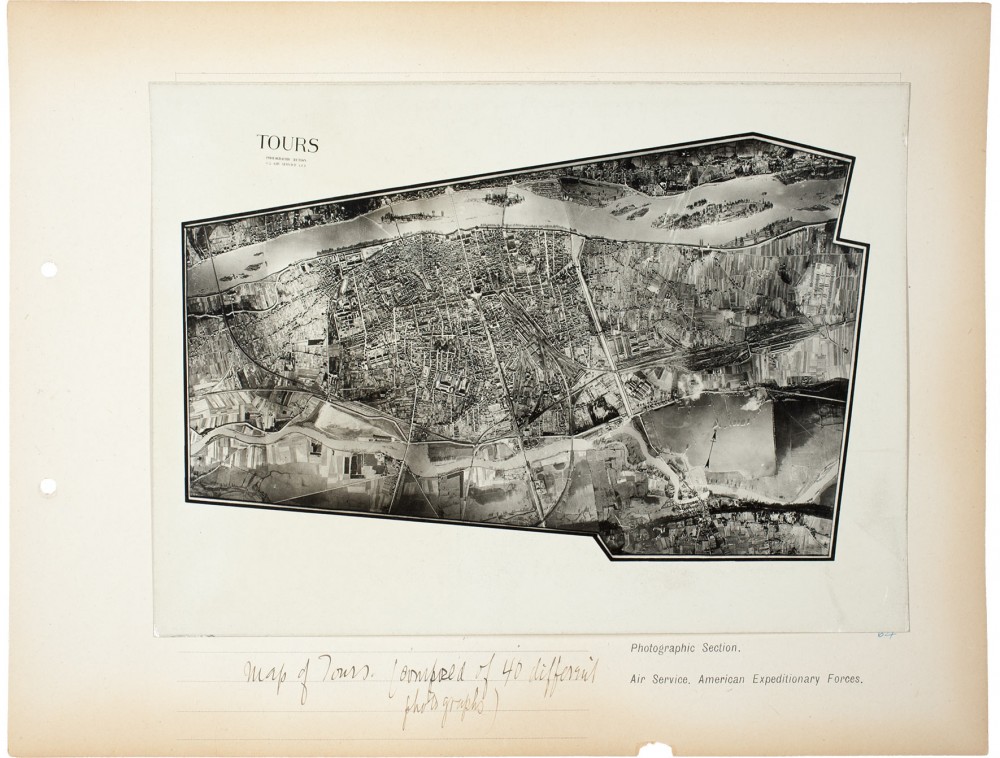

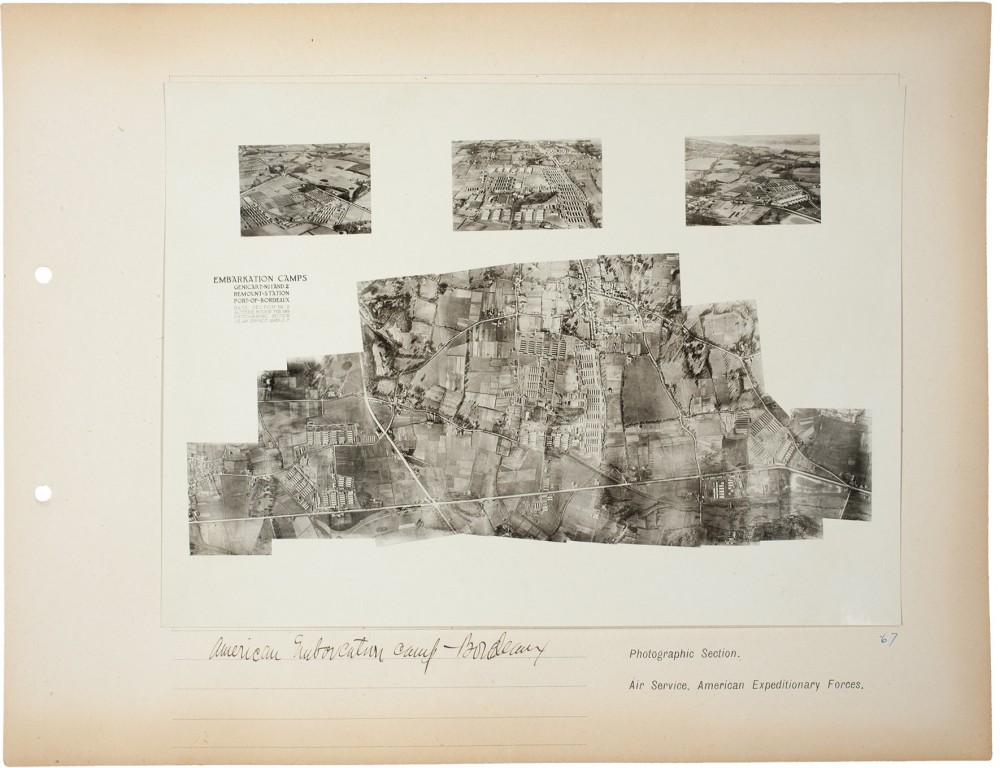

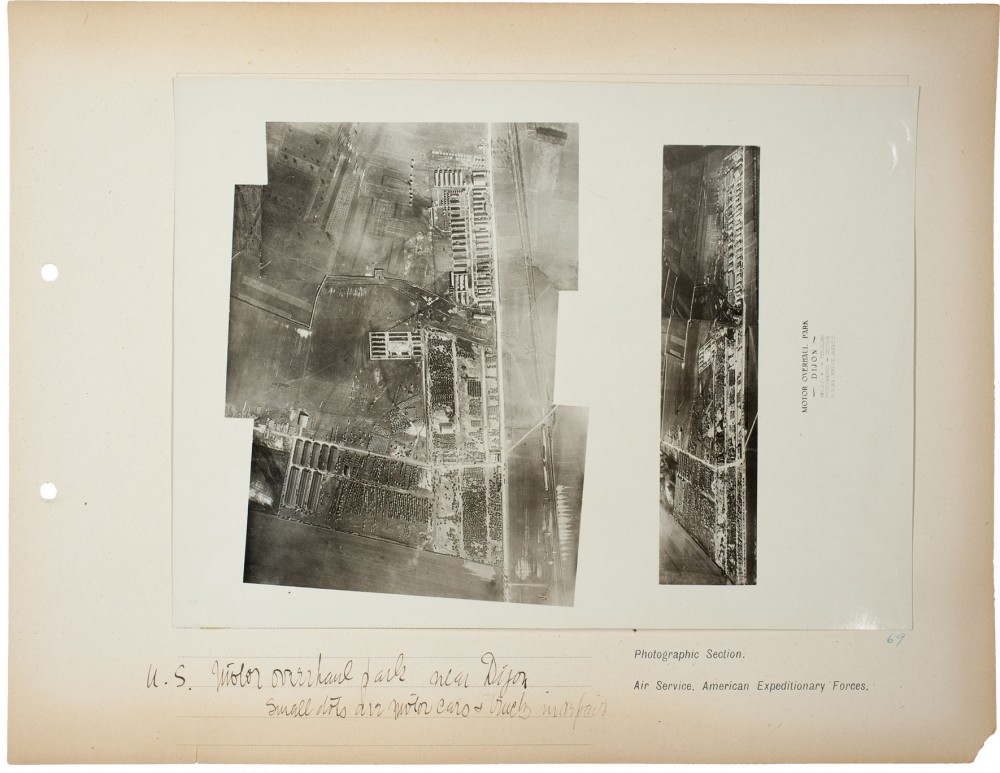

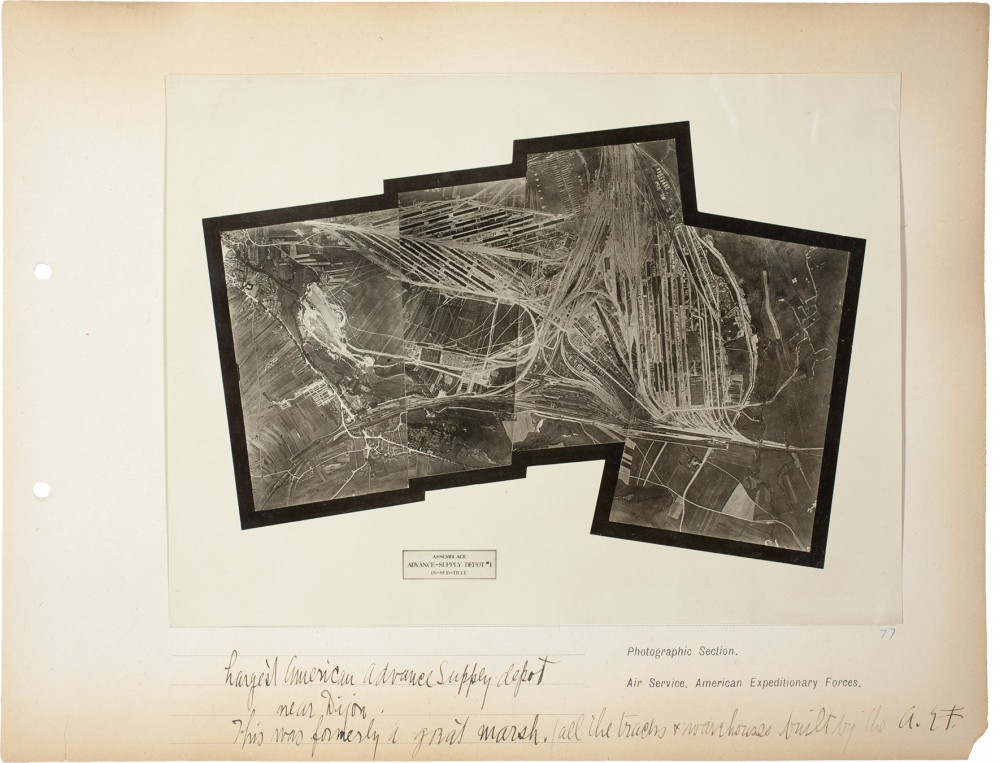

The First World War, sometimes called the first “modern” war, was marked by groundbreaking advances in technology, including photography. Though Steichen intended to be “a photographic reporter, as Mathew Brady had been in the Civil War,” he quickly abandoned this romantic notion to help implement one of the newest weapons of war—aerial photography.[1] Taking images from airplanes made it possible not only to observe a wide swath of the battlefield, but also to track daily changes on the front lines.

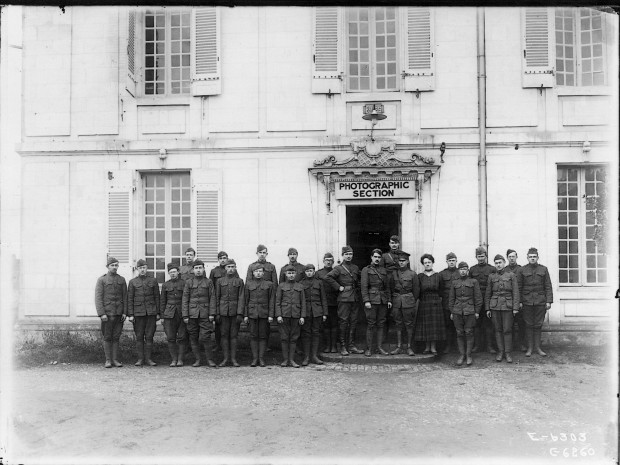

The French and British militaries had made great advances with this technology for intelligence purposes, yet the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) had no established program. Steichen was assigned to the newly formed Photographic Section, led by Major James Barnes, and together they oversaw the training and outfitting of aerial-photography and surveillance units that would prove their usefulness over the course of the war. Steichen also worked to standardize print sizes, materials, cameras, and plates across the various national armies in order to simplify the cooperation between the Allied forces.

Photographic Section, Air Service, AEF. Major Steichen and Base Photo Section at Headquarters, Air Service, Paris, France, c. 1918. Photo courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

[1] Edward Steichen, A Life in Photography (Doubleday, 1963), chap. 5, n.p.

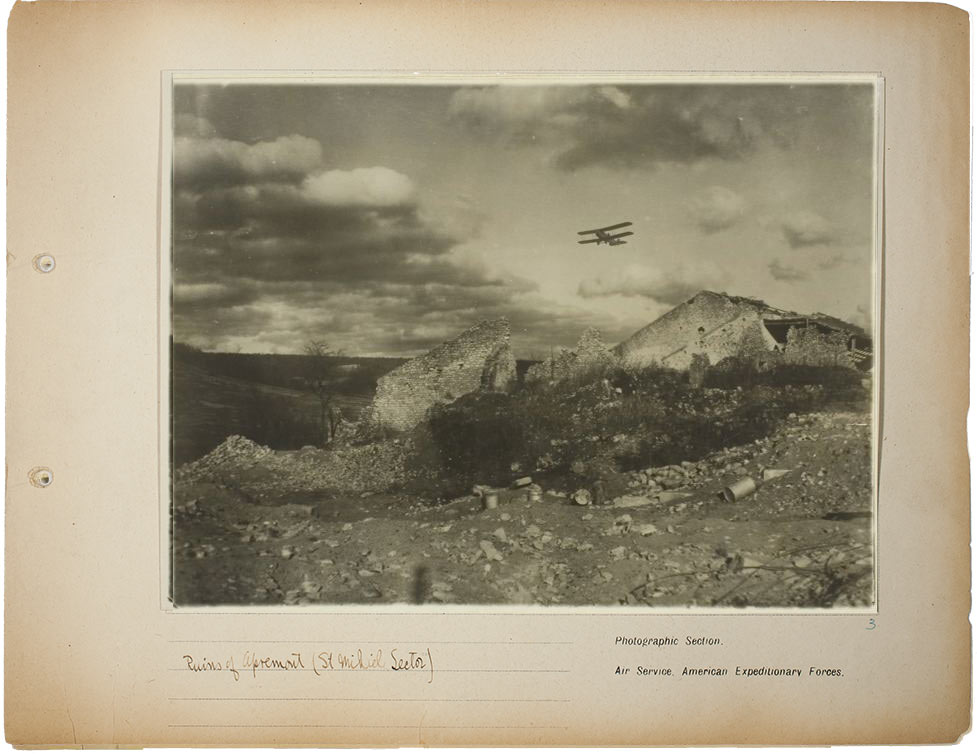

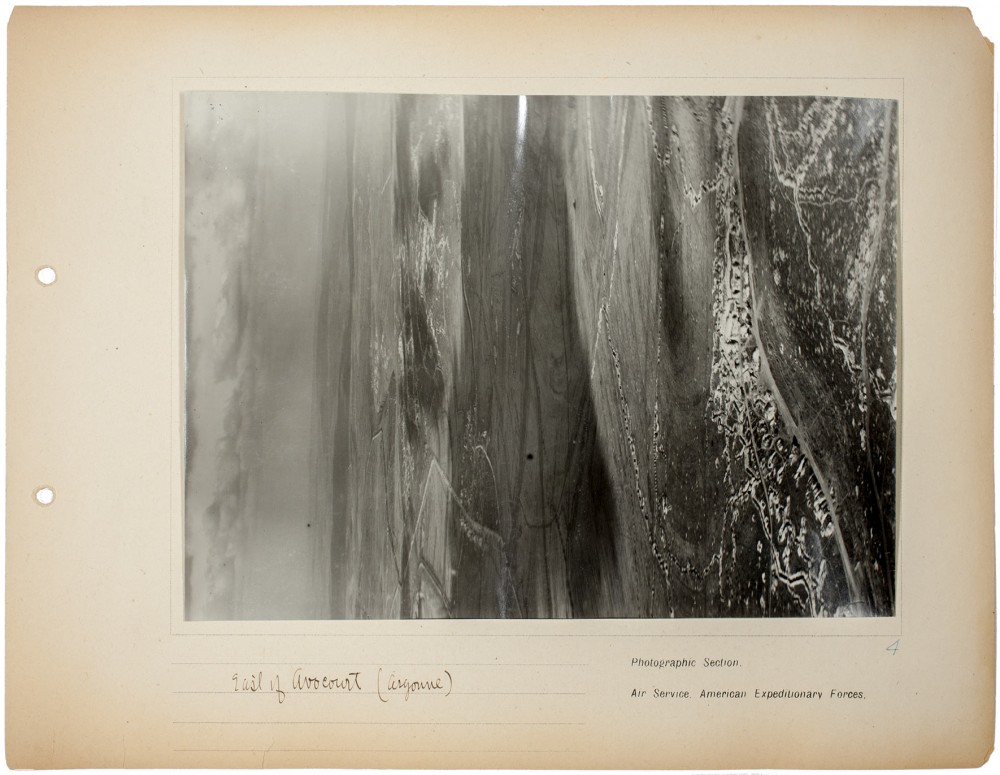

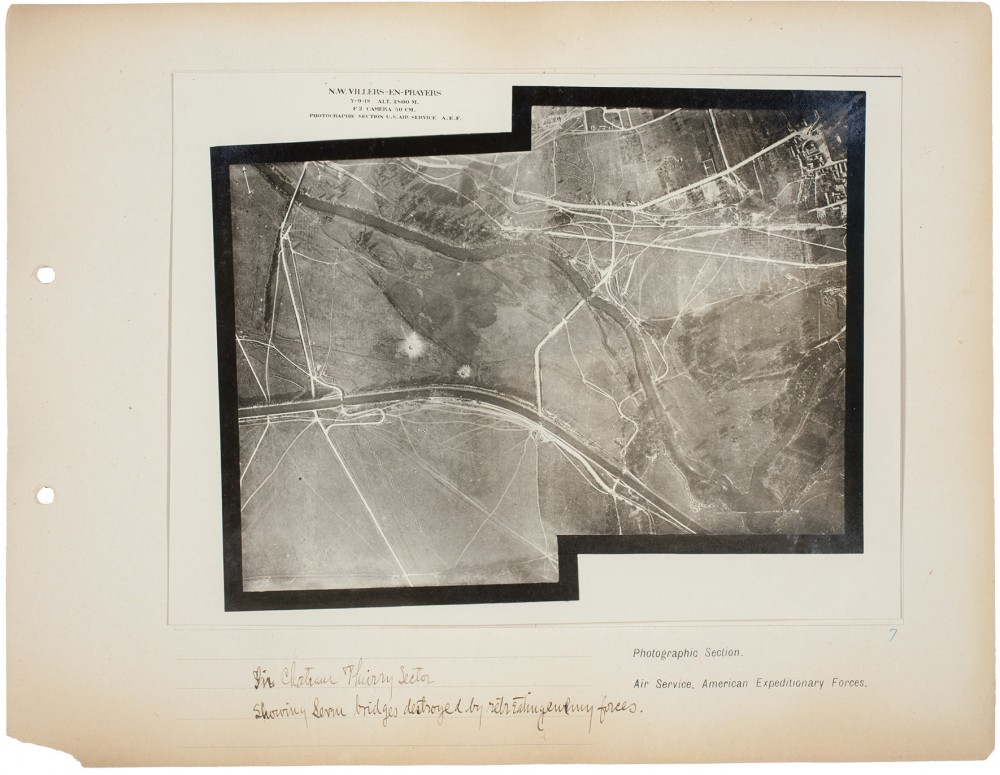

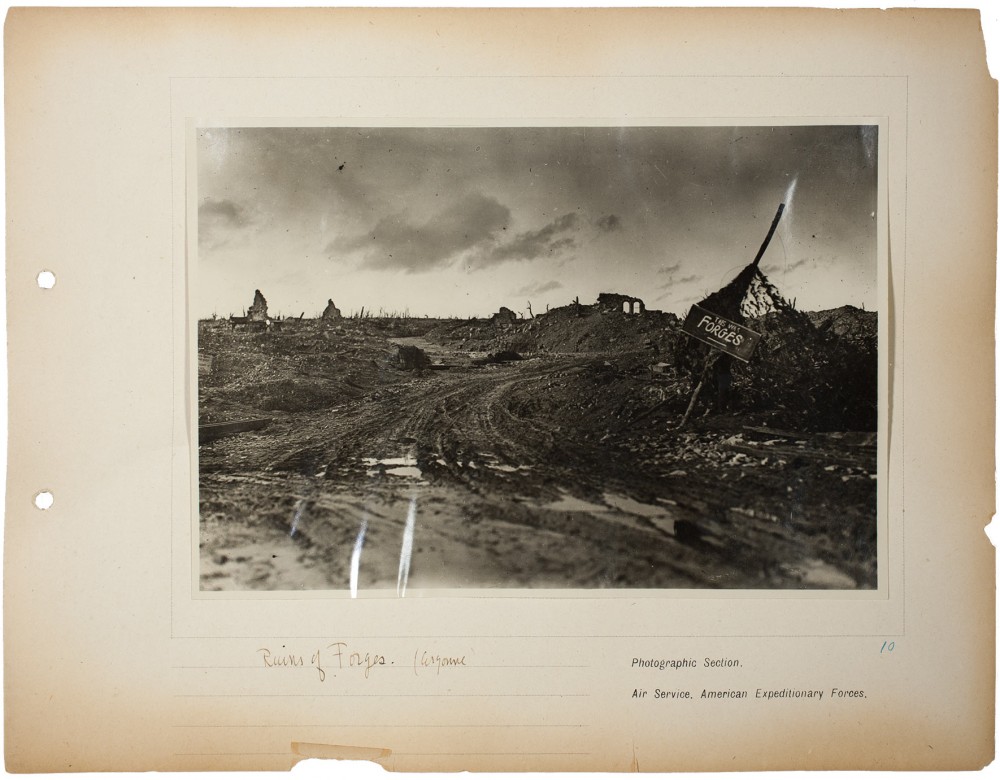

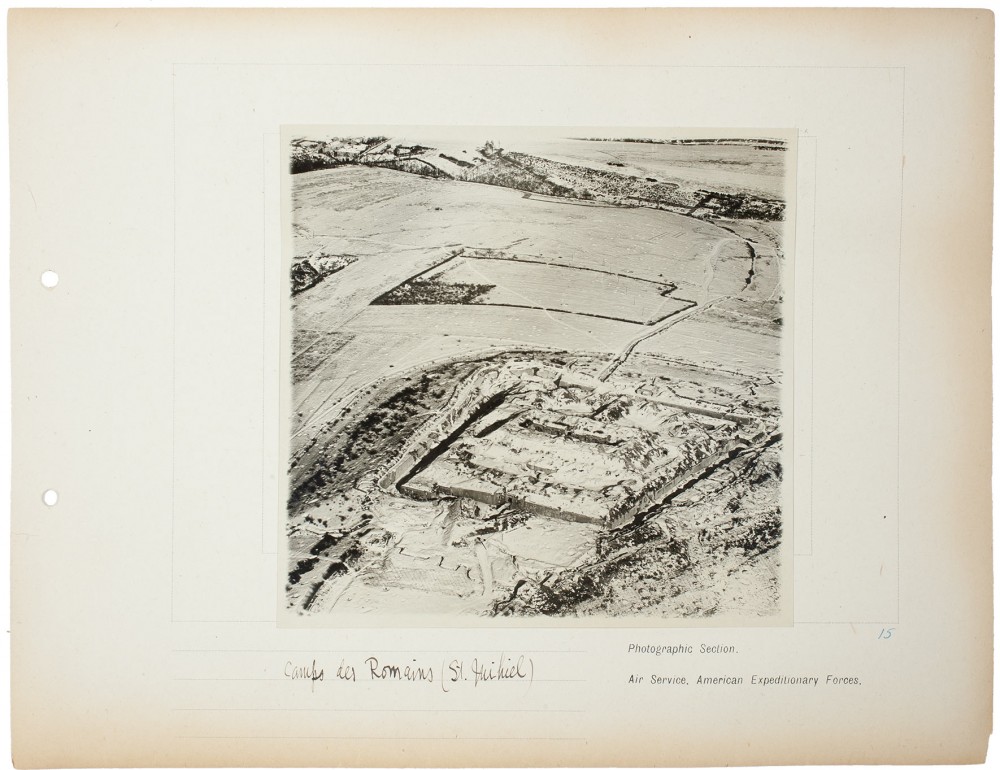

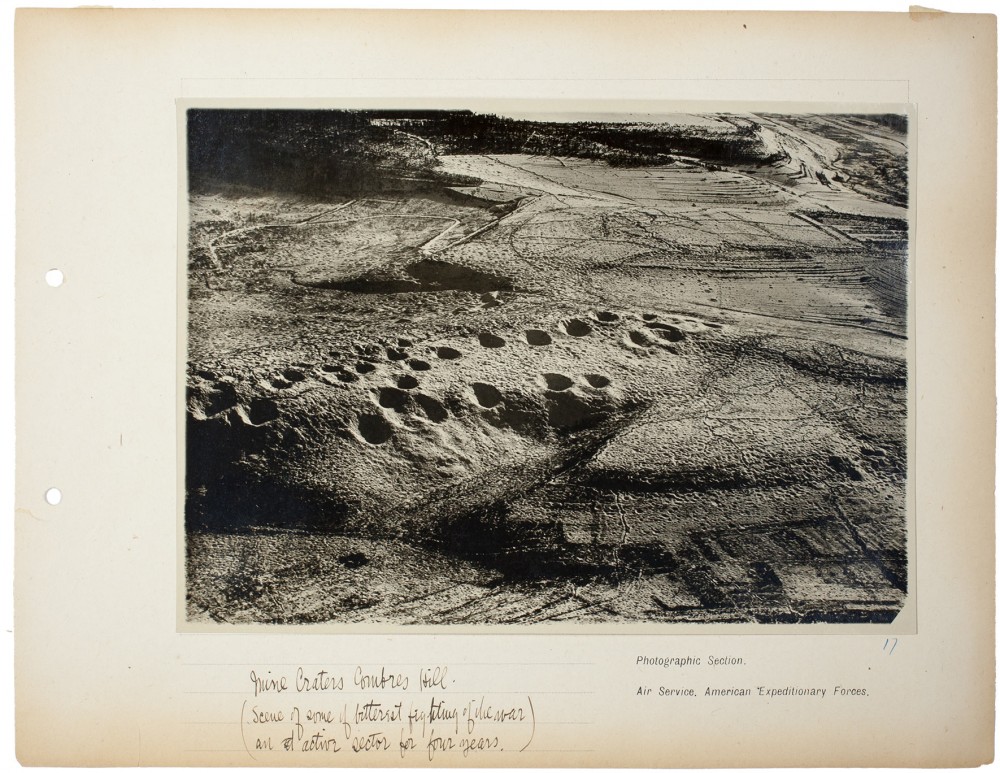

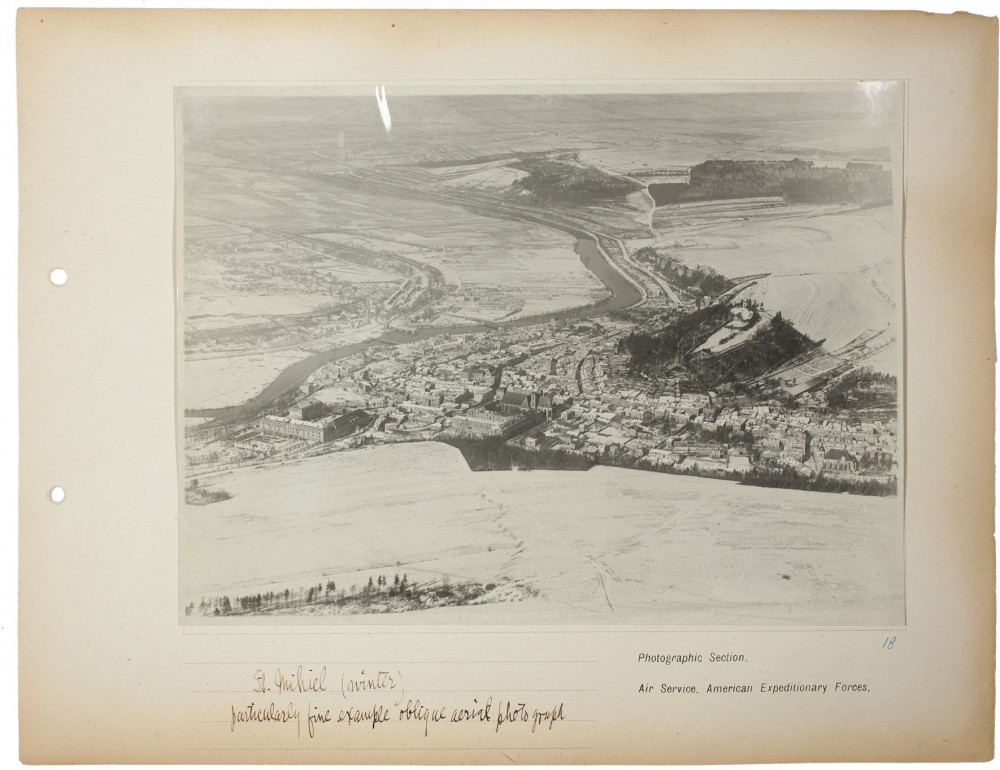

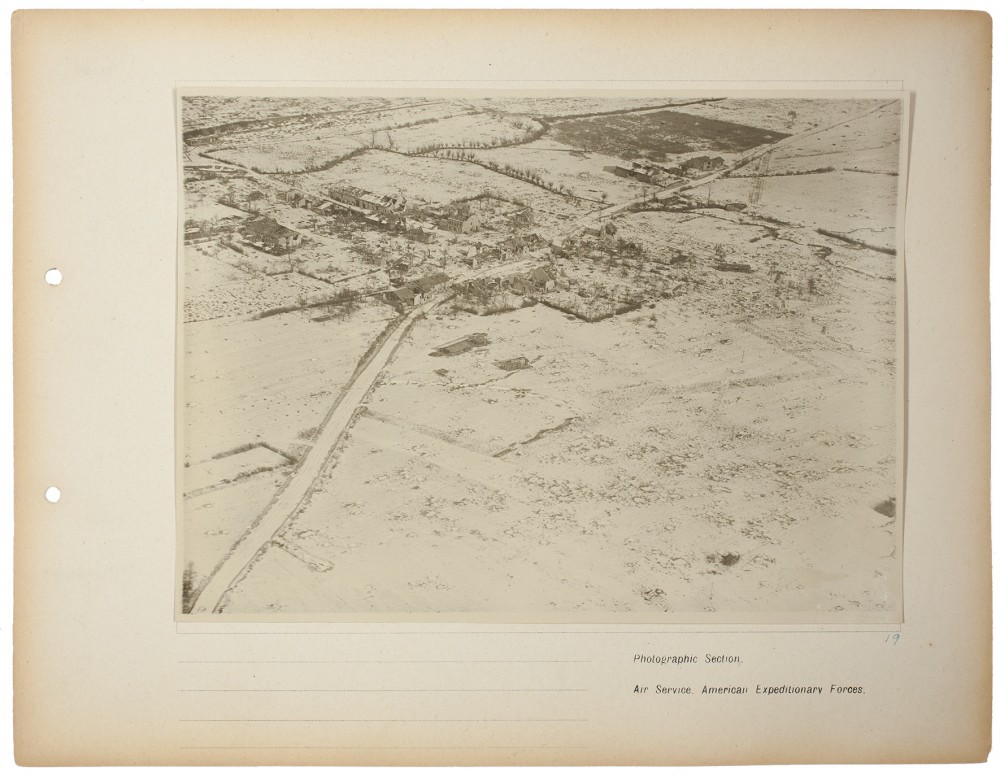

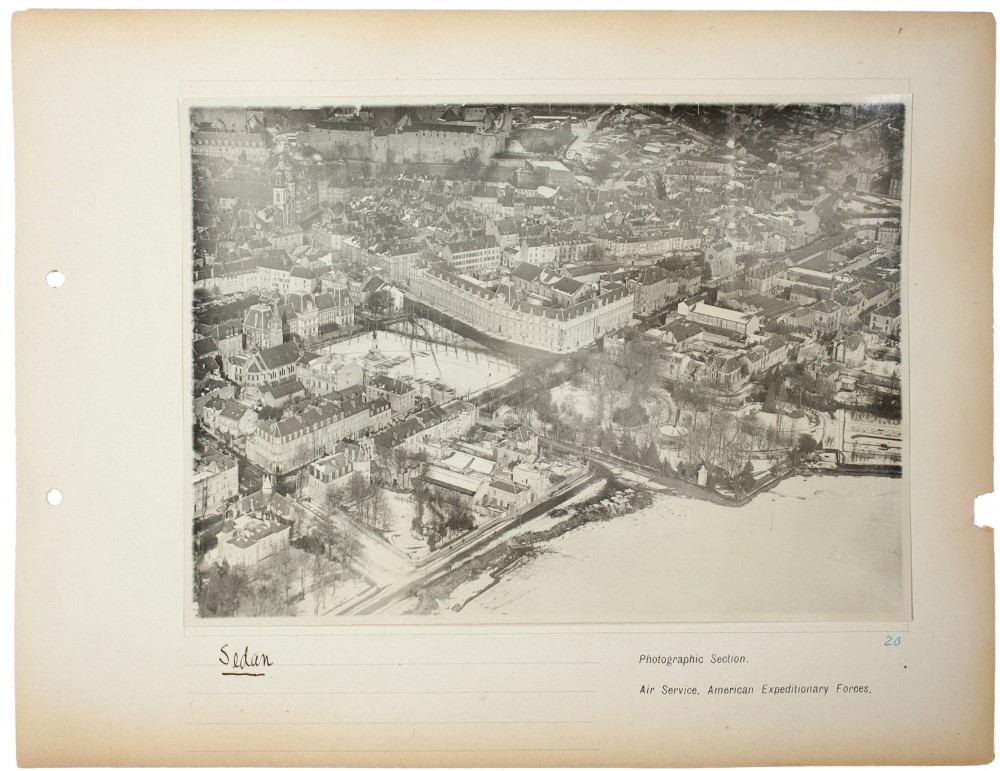

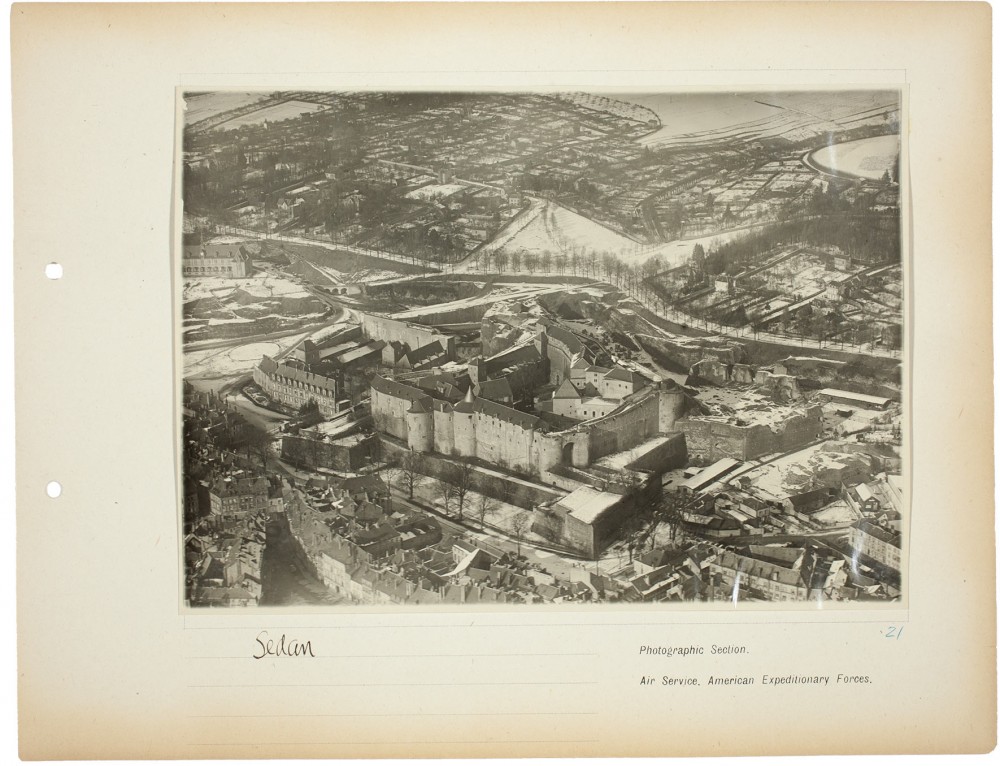

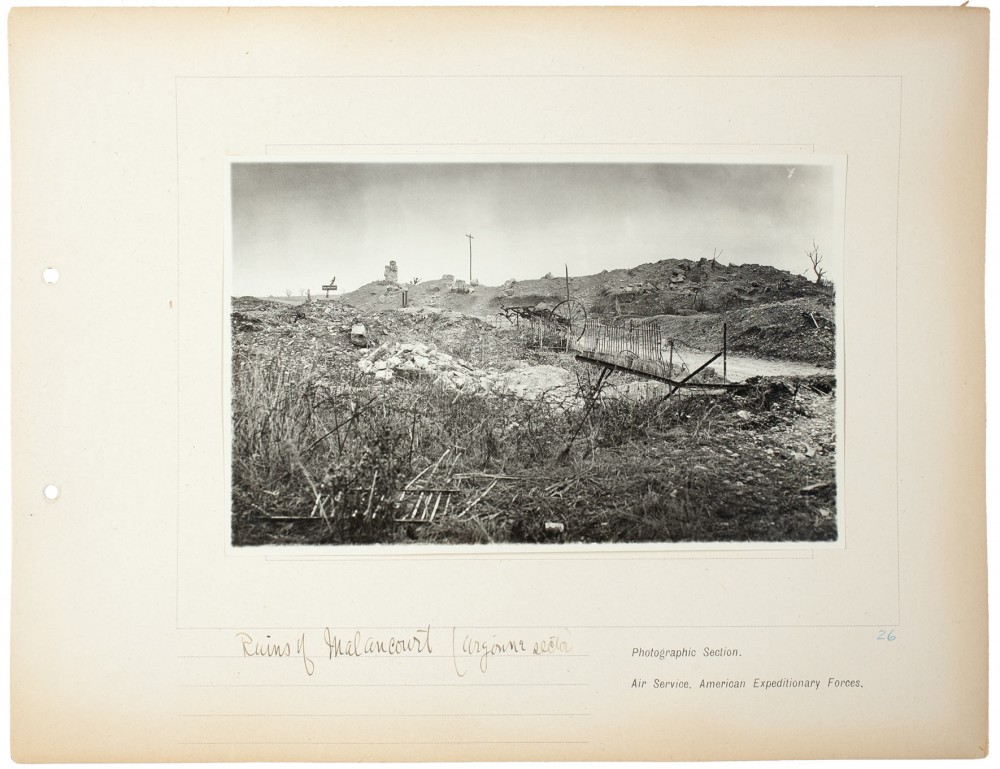

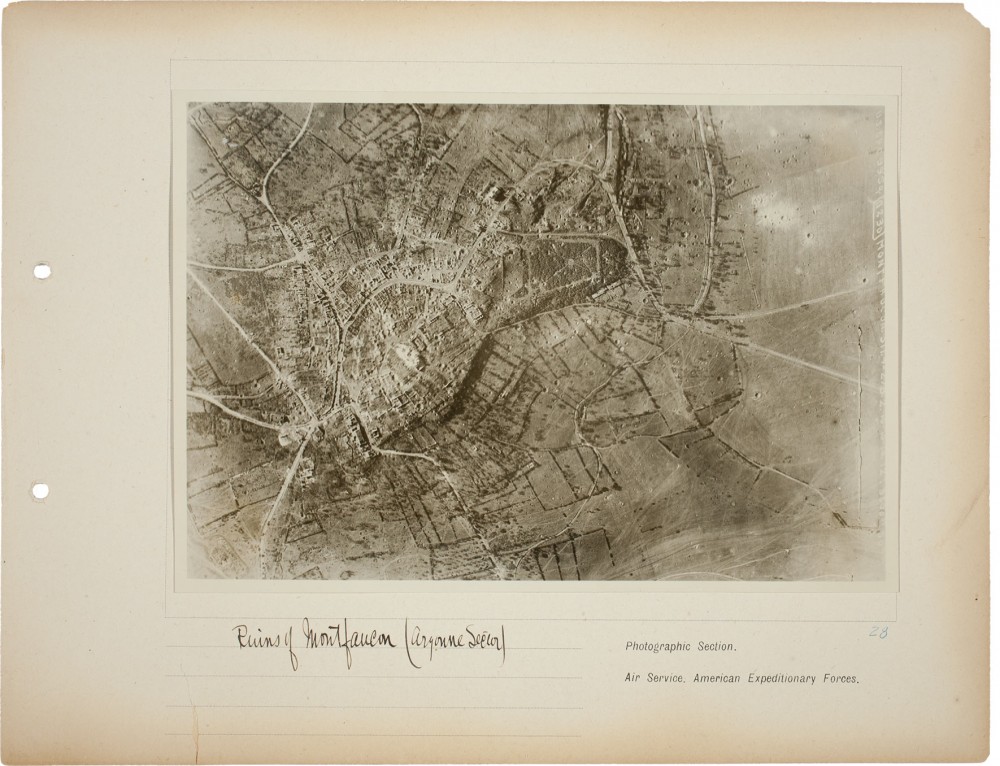

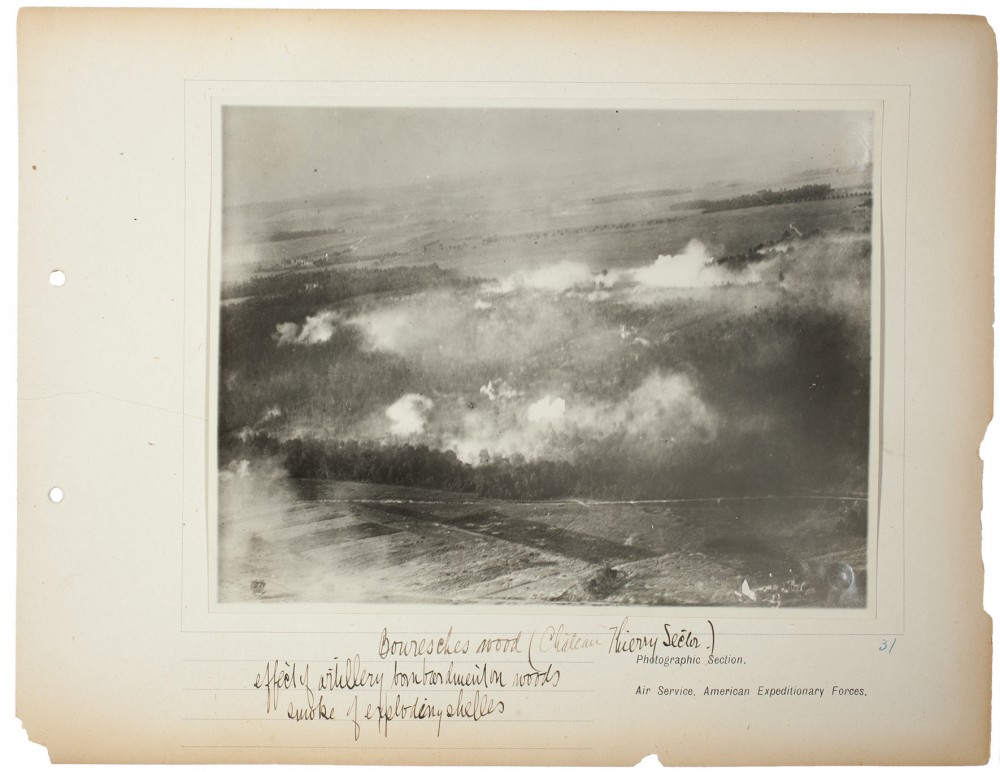

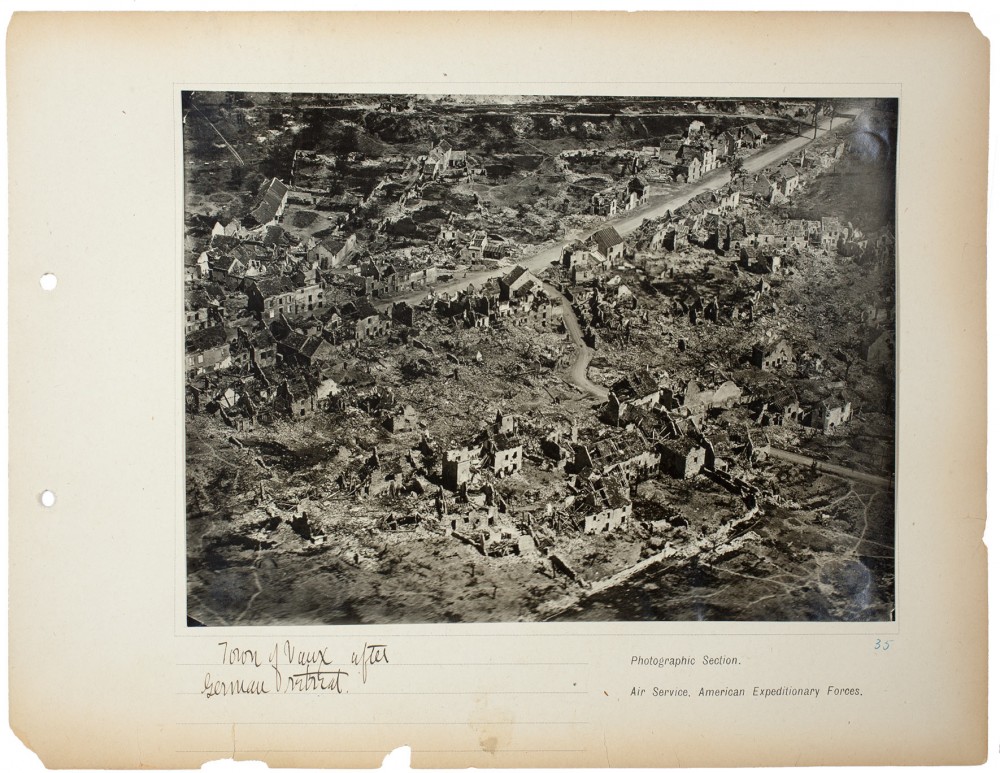

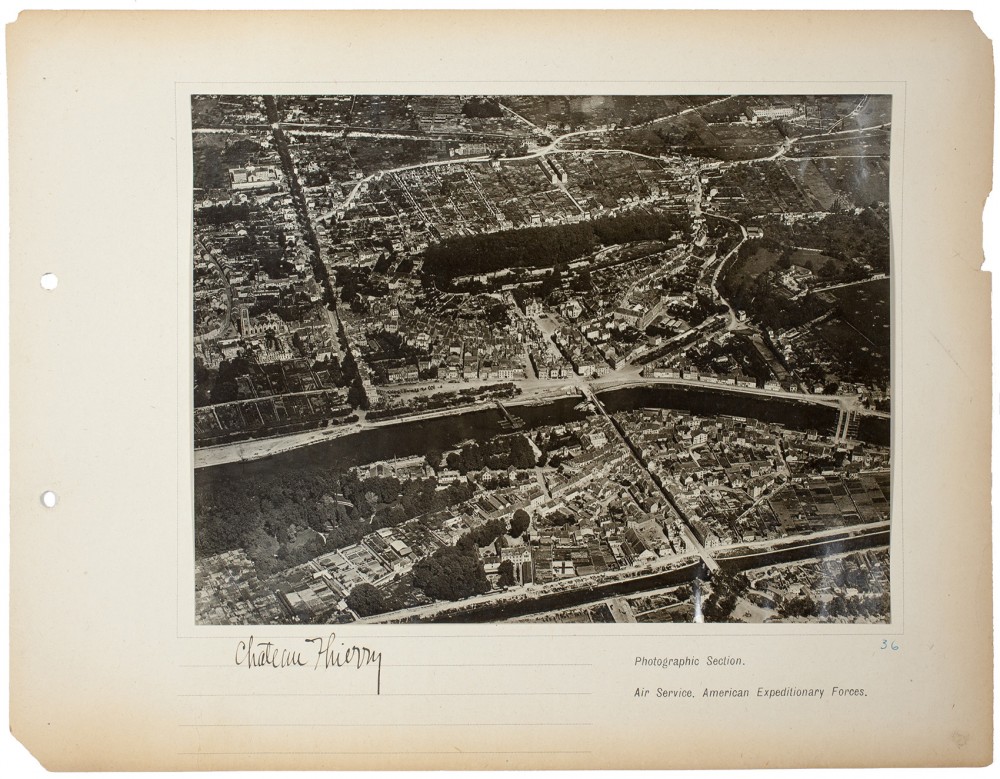

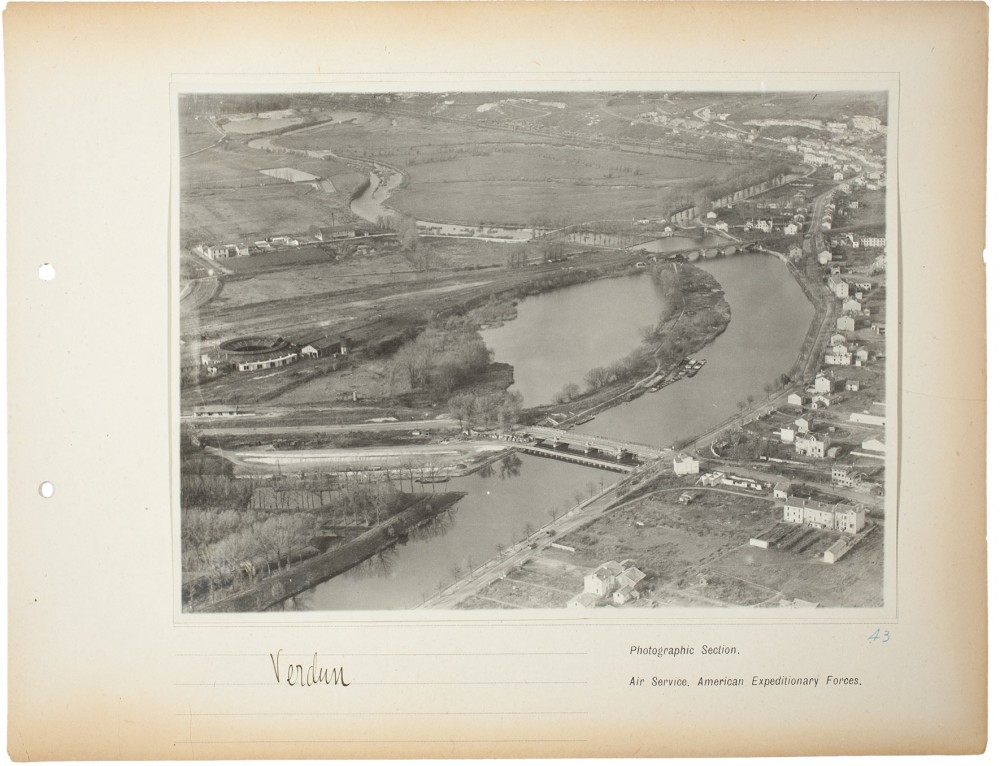

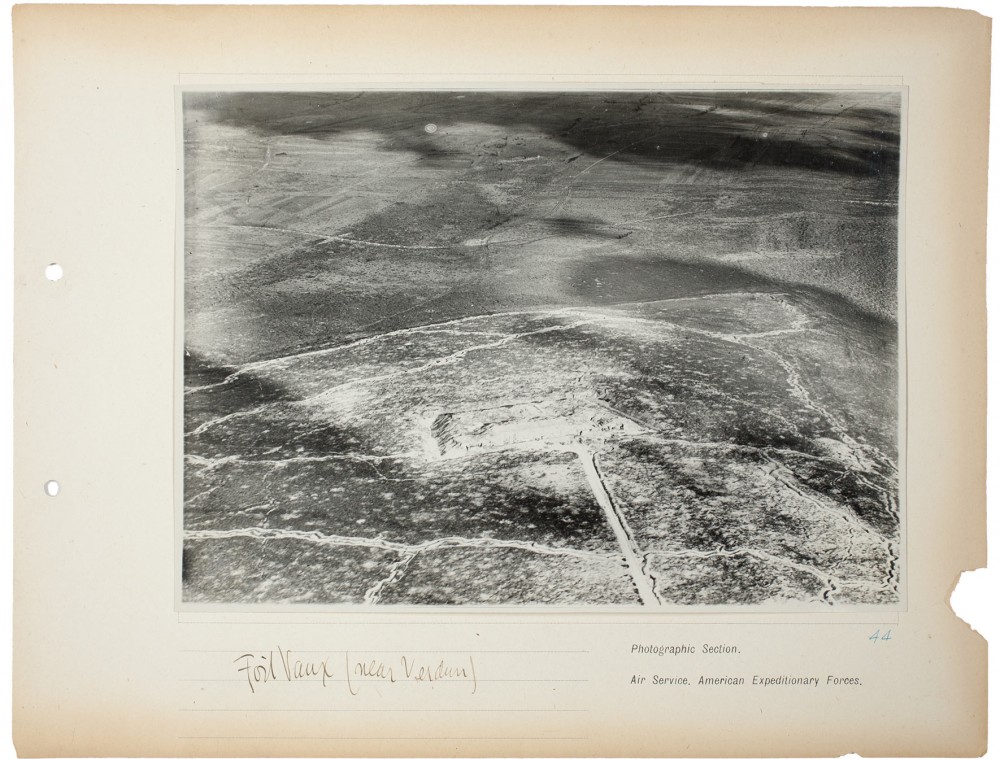

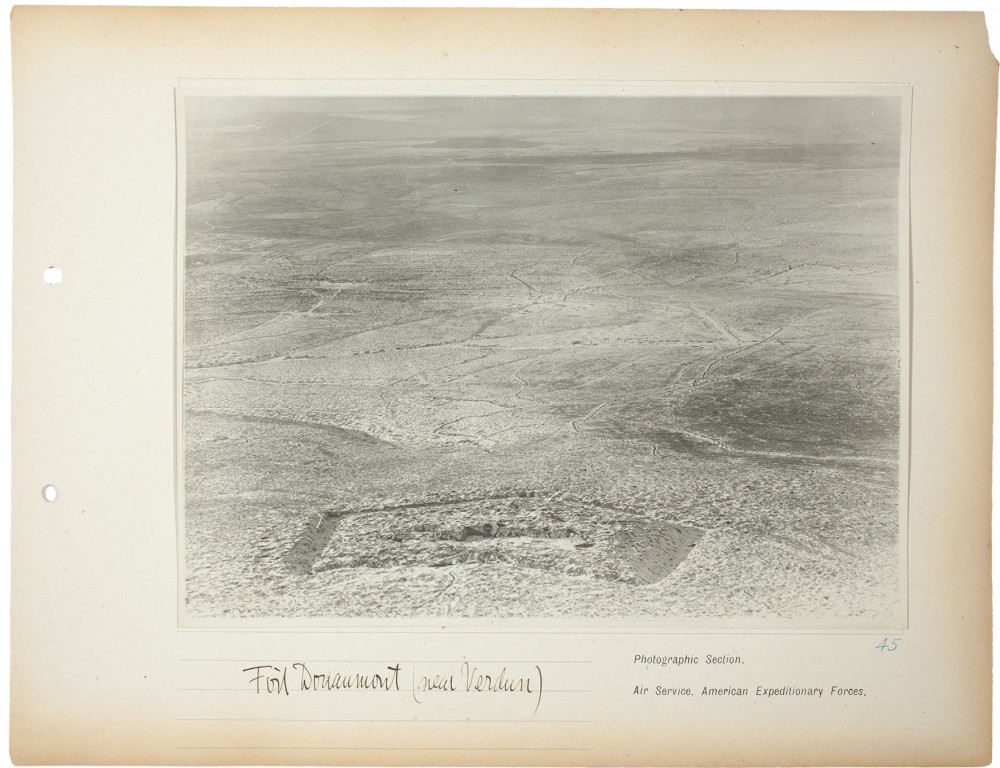

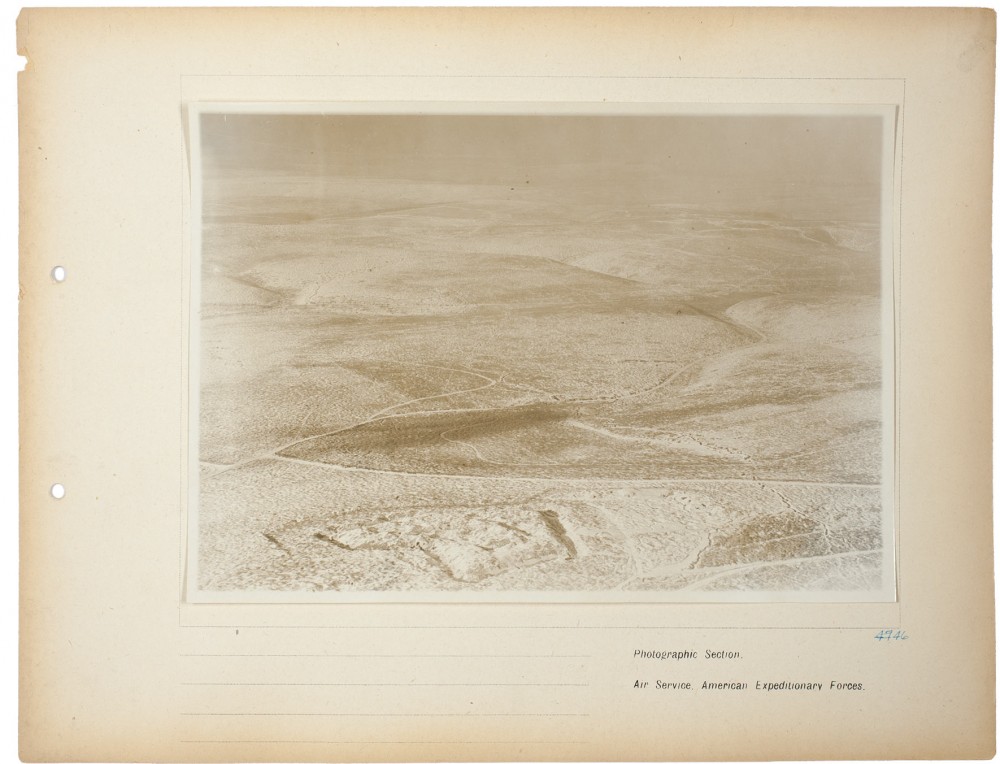

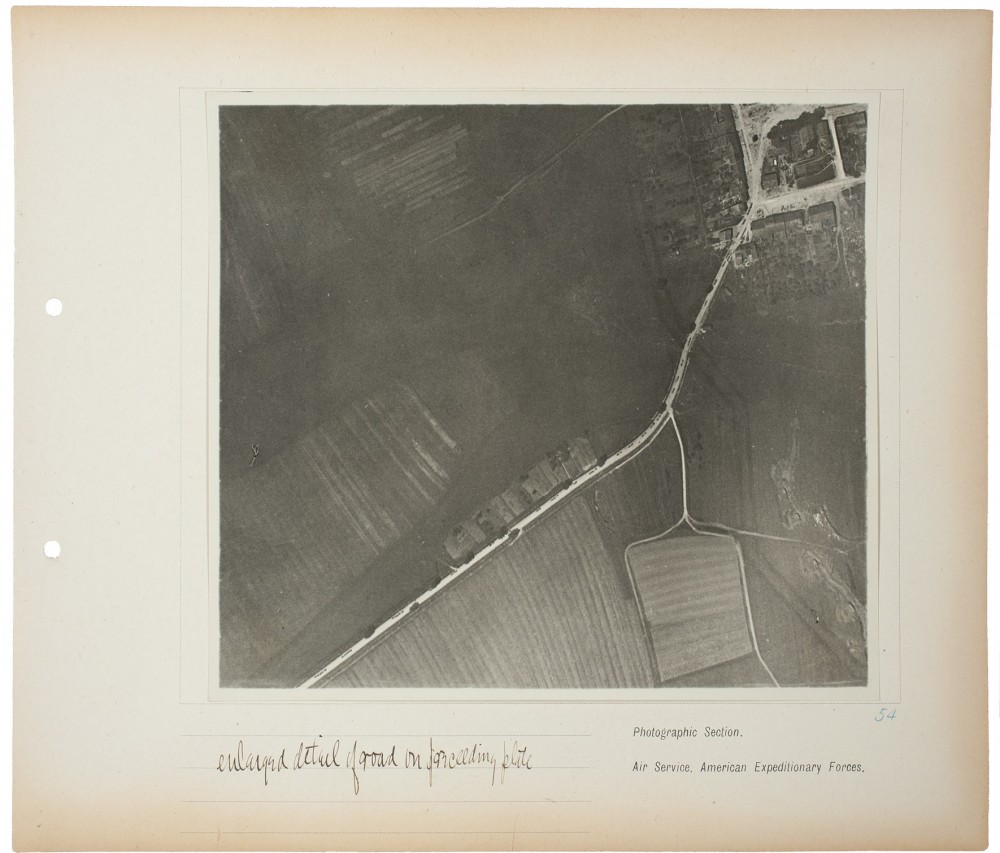

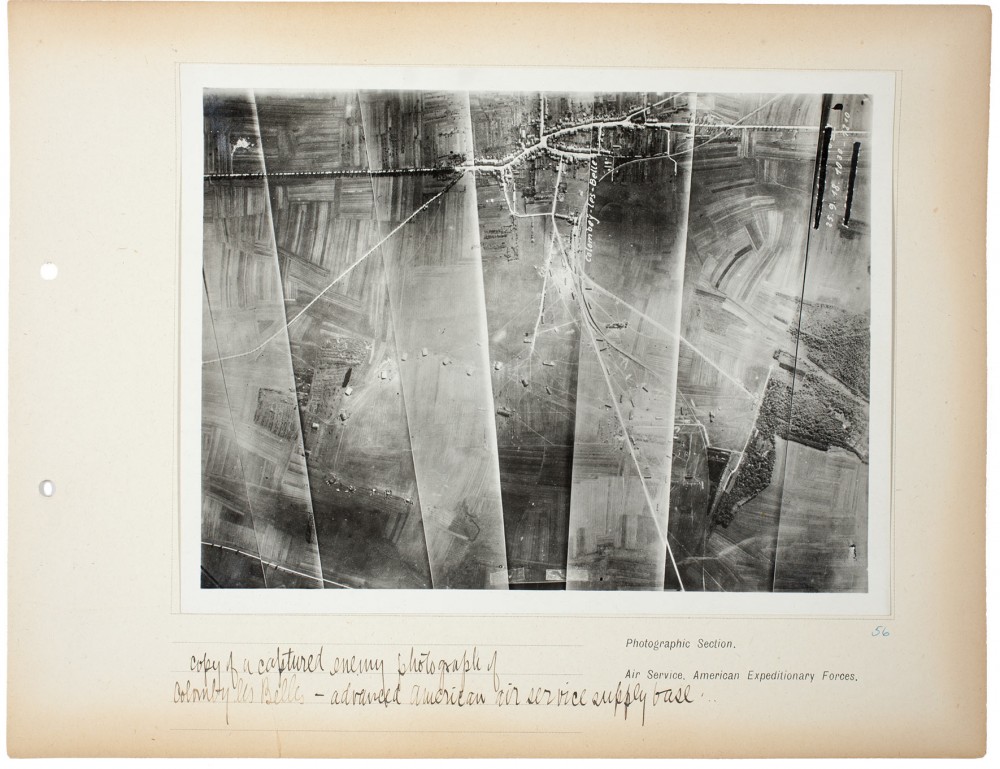

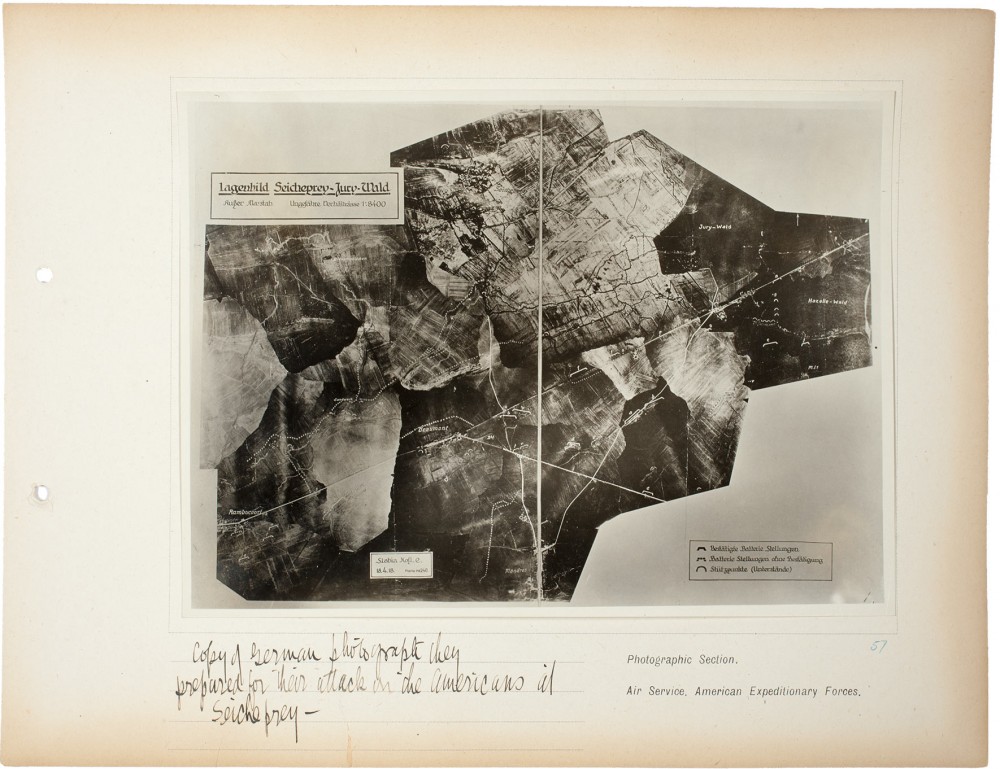

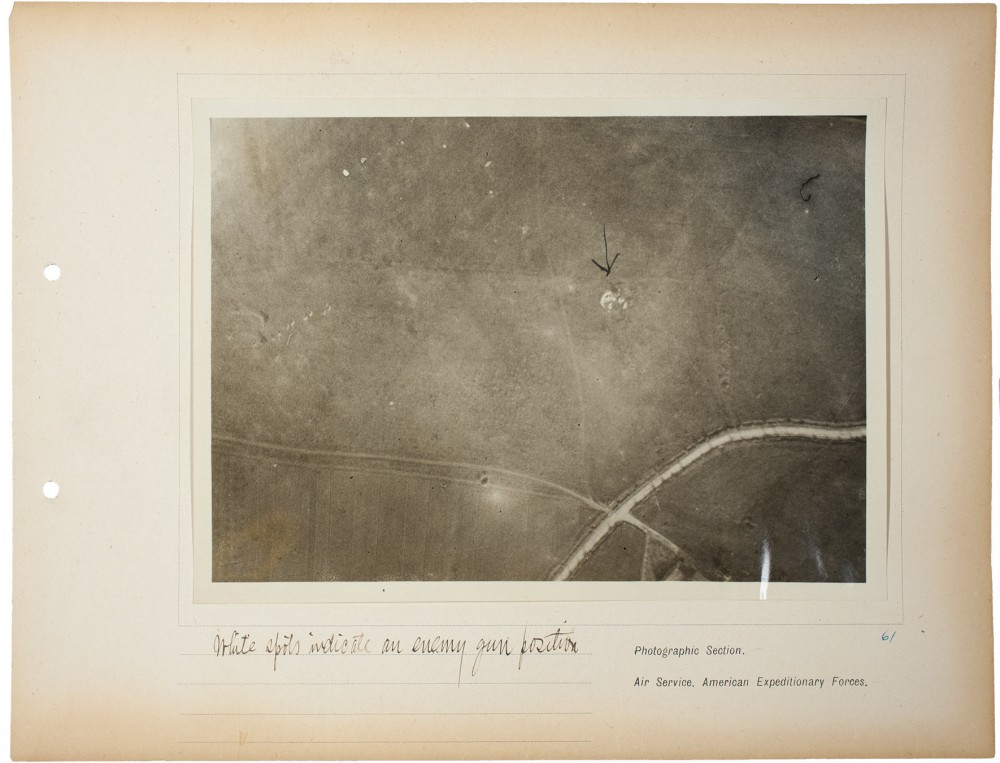

UNTITLED ALBUM OF WORLD WAR I PHOTOGRAPHS, 1918/19

All photographs taken by the Photographic Section, U.S. Air Service, American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), 1918/19

Album assembled by Major Edward J. Steichen, A.S.A. (American, born Luxembourg, 1879–1973) in 1919

83 gelatin silver prints

Gift of William Kistler, 1977.678–760

Plate titles are based on Steichen’s own written captions of the photographs. More detailed inscription information and research on the photographs can be found by clicking on the album pages. For a complete list of the album plates, click here.

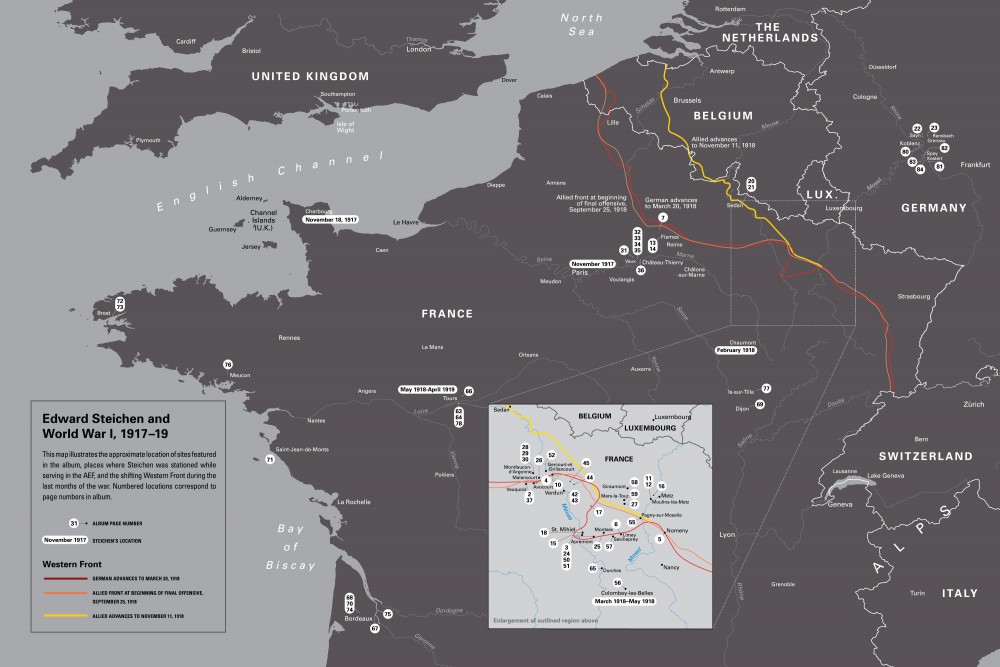

The map below shows the sites featured in the album, places Steichen was stationed while serving in the AEF, and the shifting Western Front during the last months of the war.

Plate List

All photographs taken by the Photographic Section, U.S. Air Service, American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), 1918/19

Album assembled and annotated by Major Edward J. Steichen, A.S.A. (American, born Luxembourg, 1879–1973) in 1919

83 gelatin silver prints

Gift of William Kistler, 1977.678–760

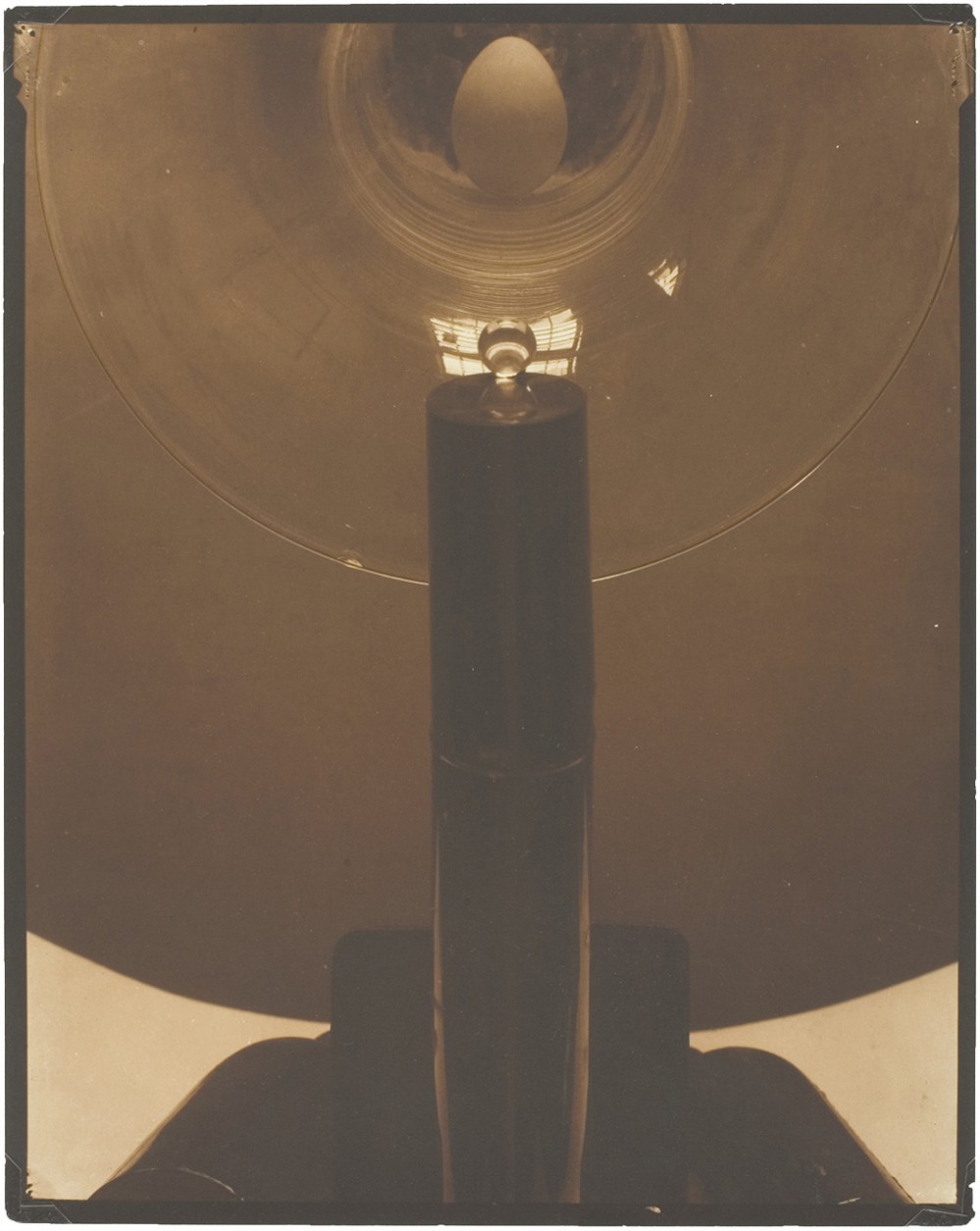

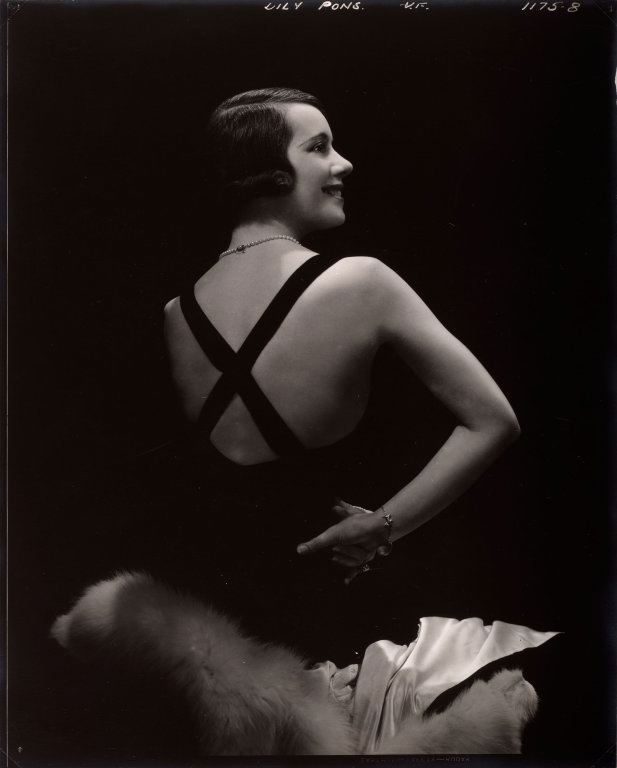

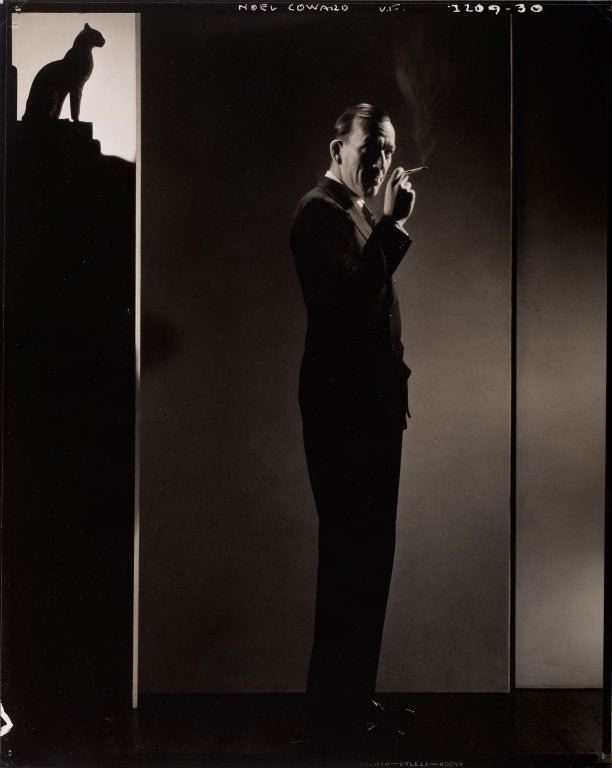

Steichen after the War

After serving with the AEF, Steichen would depart from the painterly aesthetics of Pictorialism. He fully embraced commercial work, and the technical precision required by wartime photography can be seen in his commercial images, which blur the lines between celebrity portraiture, fashion photography, and advertising. With the start of World War II, he would reenlist, overseeing a photographic unit tasked with documenting the activities of the Naval Air Force.

![Plate 2. Untitled [Vauquois]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.210-150x115.jpg)

![Plate 14. Fismes, vertical photos [Château Thierry Sector]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.141-150x116.jpg)

![Plate 22. Set of consecutive photographs [Germany]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.221-150x116.jpg)

![Plate 23. Same as preceding plate [Germany]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.231-150x116.jpg)

![Plate 24. A photographic map, forest of Apremont [St. Mihiel Sector]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.241-150x116.jpg)

![Plate 25. Montsec [St. Mihiel Sector]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.251-150x115.jpg)

![Plate 29. Montfaucon [Argonne Sector]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.291-150x114.jpg)

![Plate 30. Montfaucon (winter) [Argonne Sector]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.301-150x114.jpg)

![Plate 32. Untitled [Vaux]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.321-150x117.jpg)

![Plate 34. Untitled [Vaux]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.341-150x116.jpg)

![Plate 38. Untitled [Montmedy]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.381-150x116.jpg)

![Plate 39. Untitled [Montmedy]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.391-150x115.jpg)

![Plate 49. Untitled [Otho Cushing drawing]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.491-150x115.jpg)

![Plate 51. Interpretation of preceding picture [Apremont]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.511-150x114.jpg)

![Plate 58. Stages of a new German airdrome [Giraumont]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.581-150x115.jpg)

![Plate 59. Untitled [Mars-la-Tour]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.591-150x115.jpg)

![Plate 65. Untitled [Ourches]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.651-150x113.jpg)

![Plate 68. Untitled [Souge]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.681-150x114.jpg)

![Plate 70. Untitled [Souge]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.701-150x115.jpg)

![Plate 71. Untitled [Saint-Jean-de-Monts]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.711-150x114.jpg)

![Plate 72. Untitled [Brest]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.721-150x115.jpg)

![Plate 73. Untitled [Brest]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.731-150x114.jpg)

![Plate 74. 10,000 Beds [Souge]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.741-150x116.jpg)

![Plate 75. Untitled [Port of Bordeaux]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.751-150x113.jpg)

![Plate 76. Untitled [Meucon]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.761-150x115.jpg)

![Plate 79. Untitled [General John J. Pershing]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.791-150x114.jpg)

![Plate 80. Untitled [Fort Alexander, Koblenz]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.801-150x115.jpg)

![Plate 81. Untitled [Burg Maus on Rhine]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.811-150x115.jpg)

![Plate 82. Untitled [Marksburg Castle]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.821-150x116.jpg)

![Plate 83. Untitled [Niederspay]](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.831-150x117.jpg)

![Plate 2. Untitled [Vauquois], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.678.2-1000x768.jpg)

![Plate 14. Fismes, vertical photos [Château Thierry Sector], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.690-1000x773.jpg)

![Plate 22. Set of consecutive photographs [Germany], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.698-1000x774.jpg)

![Plate 23. Same as preceding plate [Germany], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.699-1000x776.jpg)

![Plate 24. A photographic map, forest of Apremont [St. Mihiel Sector], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.700-1000x772.jpg)

![Plate 25. Montsec [St. Mihiel Sector], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.701-1000x768.jpg)

![Plate 29. Montfaucon [Argonne Sector], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.705-1000x762.jpg)

![Plate 30. Montfaucon (winter) [Argonne Sector], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.706-1000x763.jpg)

![Plate 32. Untitled [Vaux], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.708-1000x782.jpg)

![Plate 34. Untitled [Vaux], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.710-1000x775.jpg)

![Plate 38. Untitled [Montmedy], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.714-1000x775.jpg)

![Plate 39. Untitled [Montmedy], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.715-1000x769.jpg)

![Plate 49. Untitled [Otho Cushing drawing], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.725-1000x768.jpg)

![Plate 51. Interpretation of preceding picture [Apremont], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.727-1000x763.jpg)

![Plate 58. Stages of a new German airdrome [Giraumont], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.734-1000x767.jpg)

![Plate 59. Untitled [Mars-la-Tour], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.735-1000x769.jpg)

![Plate 65. Untitled [Ourches], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.741-1000x756.jpg)

![Plate 68. Untitled [Souge], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.744-1000x762.jpg)

![Plate 70. Untitled [Souge], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.746-1000x768.jpg)

![Plate 71. Untitled [Saint-Jean-de-Mont], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.747-1000x762.jpg)

![Plate 72. Untitled [Brest], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.748-1000x764.jpg)

![Plate 73. Untitled [Brest], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.749-1000x763.jpg)

![Plate 74. 10,000 Beds [Souge], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.750-1000x770.jpg)

![Plate 75. Untitled [Port of Bordeaux], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.751-1000x755.jpg)

![Plate 76. Untitled [Meucon], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.752-1000x764.jpg)

![Plate 79. Untitled [General John J. Pershing], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.755-1000x762.jpg)

![Plate 80. Untitled [Fort Alexander, Koblenz], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.756-1000x766.jpg)

![Plate 81. Untitled [Burg Maus on Rhine], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.757-1000x767.jpg)

![Plate 82. Untitled [Marksburg Castle], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.758-1000x773.jpg)

![Plate 83. Untitled [Niederspay], from an album of World War I aerial photography assembled by Edward Steichen, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.](../../wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/09/AIC_1977.759-1000x781.jpg)