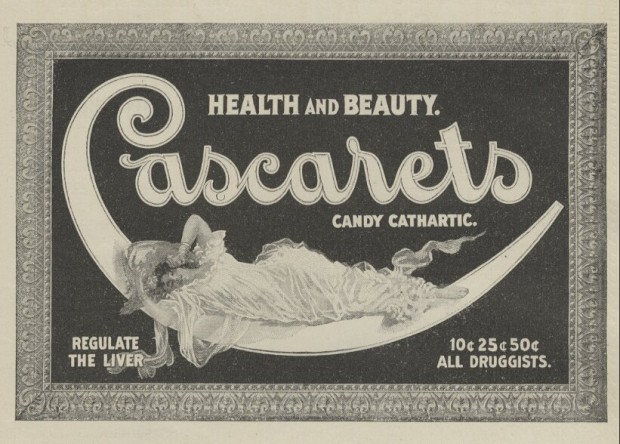

Steichen began his artistic career at the age of 16, working as a design apprentice in a Milwaukee lithographic firm, where he created photographs that were used as models for illustrated advertisements, such as in the image below. Later he recalled that his “first real effort in photography was to make photographs that were useful,” an approach to which he would return later in his career.[1]

From Munsey’s Magazine, November 1898.

In 1900 Steichen left Milwaukee and his job at a lithographic firm to pursue the artist’s life in Paris, where he befriended the sculptor Auguste Rodin, among other renowned figures, and participated in photography salons. To the right is his portrait of Rodin, a composite image that portrays the sculptor between two of his works. Steichen used two negatives to create this image—working in the darkroom to combine the silhouette of Rodin in front of his Monument to Victor Hugo with another, separate exposure of Le Penseur.

Steichen returned to the U.S. in 1902 and opened a portrait studio in New York. By then he was an aspiring painter and an accomplished photographer known for atmospheric photographs in the Pictorialist style—an aesthetic that valued retouching and evident handicraft and that aimed to distinguish fine-art photographers from ordinary professionals and hobbyists. He soon became the protégé of Alfred Stieglitz, a pioneering photographer and leading champion of American photography as an equal among the modern fine arts. Together, they opened the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known simply as 291, which first presented Picasso, Brâncusi, and a range of progressive photographers to the American public.

The two photographs titled Midnight Lake George are reverse images of each other. They show Steichen’s masterly use of a photographic process to achieve “painterly” effects. Gum bichromate emulsions have a short tonal range, meaning they cannot register vivid highlights and detailed shadow areas at the same time. Therefore, Steichen likely brightened the moon by brushing away some of the pigment during development, when the emulsion was still wet and malleable.

Also of note is the almost-vibratory appearance of the tree trunk and leaves. Gum printing is an additive process: photographers spread one layer of emulsion upon another to deepen the tone. Each time the paper is exposed, the negative must be lined up with the previously printed image, a practice known as “registering the negative.” The slight blurring suggests that Steichen did not register the negative with precision. Whether made in error or by design, effects like this emphasize the handcrafted nature of these photographs, an aspect that would have been important to the Pictorialists.

To learn more about Pictorialism and the related Arts and Crafts movement of the late 19th century, click here to explore the Art Institute’s 2010 exhibition Apostles of Beauty: Arts and Crafts from Britain to Chicago.

Figure 1. Edward J. Steichen (American, born Luxembourg, 1879–1973). Rodin, Le Penseur, 1902. Gum bichromate print; 26.2 x 32.6 cm (image/paper/mount). Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.825. © 2015 The Estate of Edward Steichen/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 2. Edward J. Steichen (American, born Luxembourg, 1879–1973). Midnight Lake George, 1904. Gum bichromate over platinum print; 39.2 x 50.6 cm. Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.829. © 2015 The Estate of Edward Steichen/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 3. Edward J. Steichen (American, born Luxembourg, 1879–1973). Midnight Lake George, 1904. Gum bichromate over platinum print; 39.2 x 50.6 cm. Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.830. © 2015 The Estate of Edward Steichen/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

[1] Edward Steichen, A Life in Photography (Doubleday, 1963), chapter 1, n.p.