Gelatin silver print

Gift of William Kistler, 1977.709

While operating close to the zone of advance was important, this also meant that facilities were often improvised. Each unit was assigned a photographic truck and trailer that served as a darkroom, but printing often occurred in spaces “found, stolen or imagined” as Steichen put it.[1] In an article written after the war, Steichen recalled that the Photographic Section prepared all the July 1918 photographs of Vaux and the Château Thierry sector in a tent:

Inside of one end of the tent a wooden framework was set up and this covered with tar paper and opaque curtains to make it light-tight. It was also just about as air-tight, but men worked steadily in shifts in this hotbox for six consecutive days and nights—and came out alive.[2]

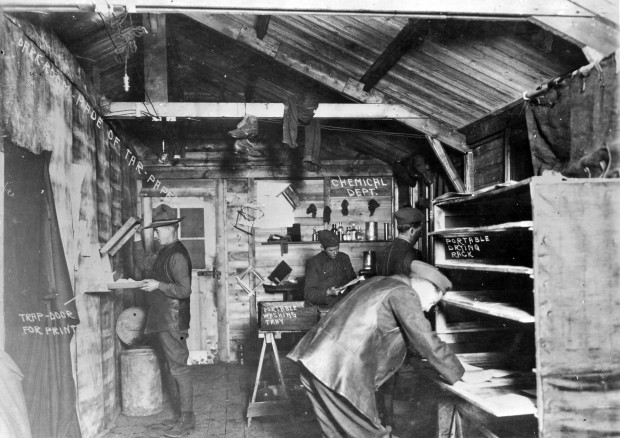

This photograph, from the 5th Photographic Section, shows the inside of a printing lab—complete with portable drying rack and washing trays. To the left a portion of the shed has been blocked off with tar paper to create a darkroom. Water for rinsing the prints was often hauled in buckets from nearby streams.

Laboratory of the 5th Photo Section, France, 1918-1919. National Archives and Records Administration. Image courtesy of Harry Kidd.

This photograph shows the 12th Photographic Section in front of one of the mobile darkroom trailers. Each man poses with a piece of the equipment needed for the process—from an airman with a camera to a lab technician wearing an apron.

12th Photo Section in France, 1918-1919. National Archives and Records Administration. Image courtesy of Harry Kidd.

Inscribed recto, on album page, lower left, in black/brown ink: “Town of Vaux. (near Chateau Thierry) / June 30 day before American attack”; printed recto, on album page, lower right, in black ink: “Photographic Section. / Air Service. American Expeditionary Forces.”; inscribed recto, on album page, lower right, in blue ink: “33”; unmarked verso

[1] Edward Steichen, “American Aerial Photography at the Front,” The Camera: The Magazine for Photographers (July 1919), p. 363.

[2] Edward Steichen, “American Aerial Photography at the Front,” The Camera: The Magazine for Photographers (July 1919), p. 363.