Steichen returned to New York in 1923, his prospects uncertain. When he came across an article in Vanity Fair reporting that he had abandoned photography for painting—in fact the opposite was true—he went to meet with Condé Nast, publisher of Vogue and Vanity Fair, to set the matter straight. Nast, who had recently lost the fashion photographer Baron Adolf de Meyer to a competing publication, offered Steichen the job of chief photographer for the two magazines. Soon thereafter Steichen signed a separate contract with the J. Walter Thompson advertising company; through these positions he became the best-known and highest-paid commercial photographer of his time.

Steichen immediately embraced celebrity, fashion, and advertising photography. He dismissed criticism that such work would tarnish his artistic reputation and championed instead the cultural and economic potential of magazine and advertising photography (in earlier years he had regularly sought portrait commissions and had once done a fashion shoot). As Vogue art director Alexander Liberman later observed, “Steichen’s work dramatized the welding of pictorial journalism with the new means of communication,” an evolution that would take place during his tenure at Condé Nast. In undertaking this challenging endeavor, the organizational and technical skills Steichen gained during his time in the military and in Voulangis proved invaluable.

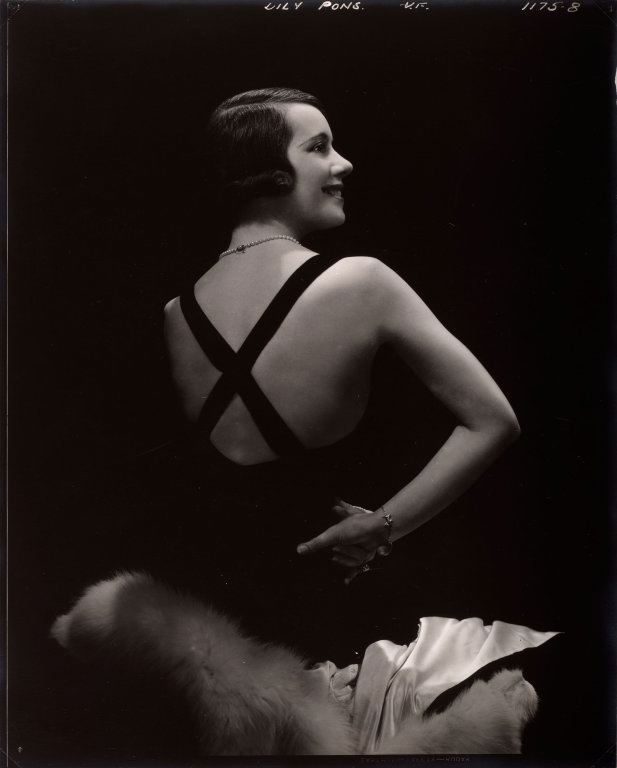

Figure 1. Edward J. Steichen (American, born Luxembourg, 1879–1973). Lily Pons, c. 1932. Gelatin silver print; 24.3 x 19 cm. Bequest of Edward Steichen by direction of Joanna T. Steichen and George Eastman House, 1982.361. © 2015 The Estate of Edward Steichen/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

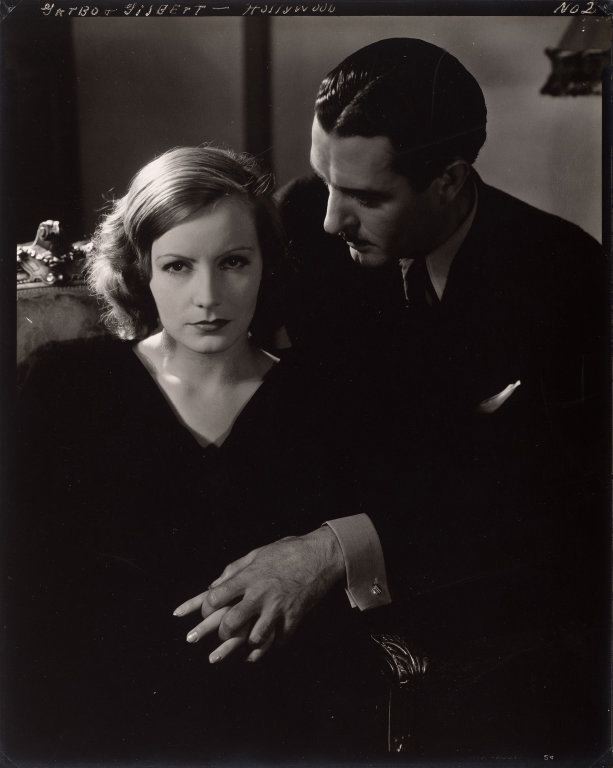

Figure 2. Edward J. Steichen (American, born Luxembourg, 1879–1973). Greta Garbo and John Gilbert, 1928. Gelatin silver print; 24.2 x 19.5 cm. Bequest of Edward Steichen by direction of Joanna T. Steichen and George Eastman House, 1982.337. © 2015 The Estate of Edward Steichen/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.