Nineteenth Century

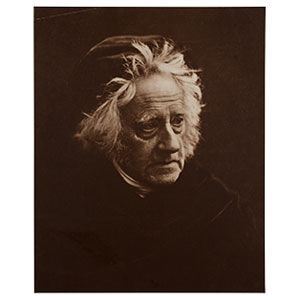

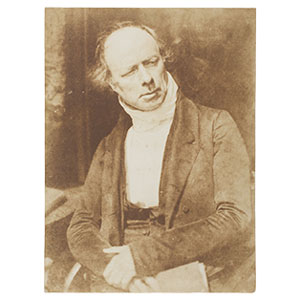

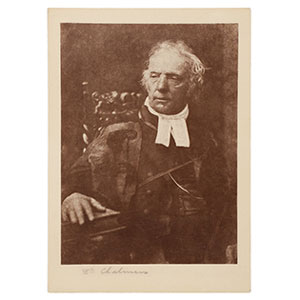

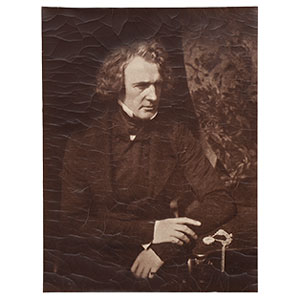

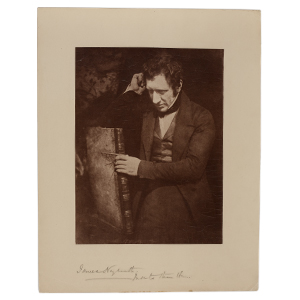

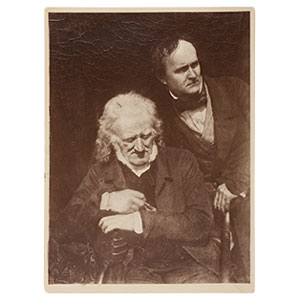

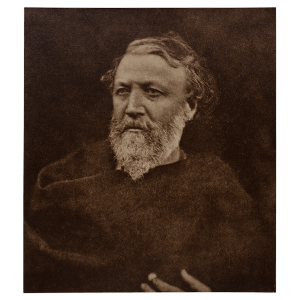

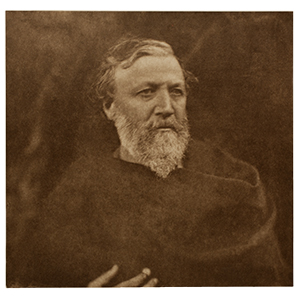

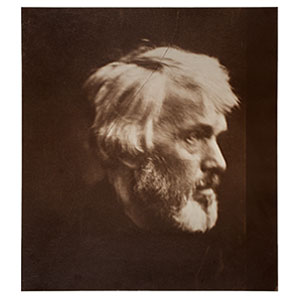

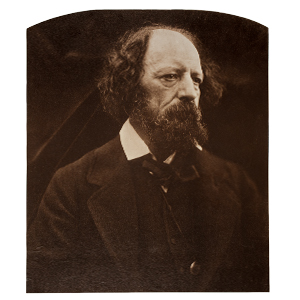

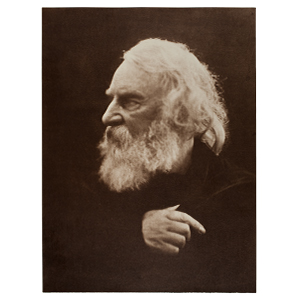

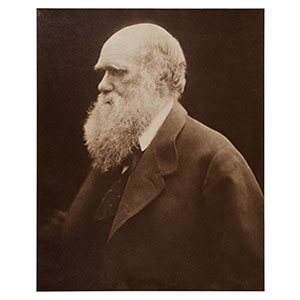

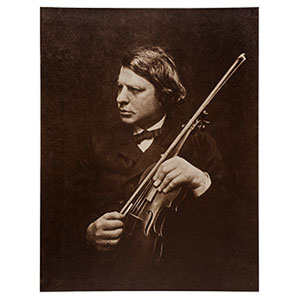

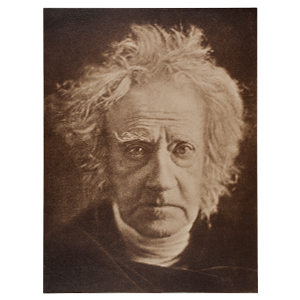

In their quest to legitimate photography as a fine art, Alfred Stieglitz and the Photo-Secession searched its short history for artistic ancestors. Yet they deemed only two nineteenth-century photographers worthy of being called true artists: David Octavius Hill (whose partner, Robert Adamson, went unacknowledged at the time) and Julia Margaret Cameron. Works by these photographers were the only non-contemporary examples in in Stieglitz’s collection.

The Photo-Secessionists admired the work of Hill and Adamson for its composition, in which masses of form are emphasized over line, and praised Cameron’s portraits for subsuming surface detail to emotional intensity. Although these artists were deceased by the turn of the century, their reputations were revived in part by people from Stieglitz’s circle: James Craig Annan made new photogravures from Hill and Adamson’s original paper negatives for publication and exhibition, Frederick H. Evans favorably reviewed Cameron’s work in London, and photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn included works from both oeuvres in a 1915 exhibition titled The Old Masters of Photography.

Stieglitz also played a significant role in this retrieval of a photographic past. He featured the work of Hill and Adamson (in 1905, 1909, and 1912) and Cameron (in 1913) in Camera Work—the only nineteenth-century artists to be included in those pages. He also exhibited Hill and Adamson’s prints at 291 and later in the comprehensive International Exhibition of Pictorial Photography he organized at the Albright Art Gallery in 1910, where their work was shown in higher numbers than that of any living photographer.