Pictorialism

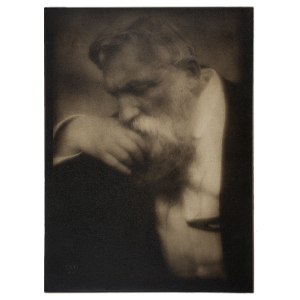

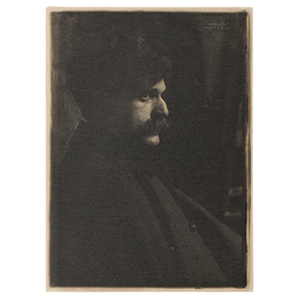

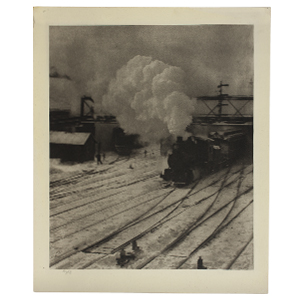

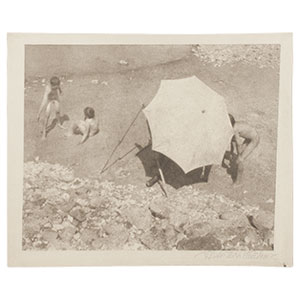

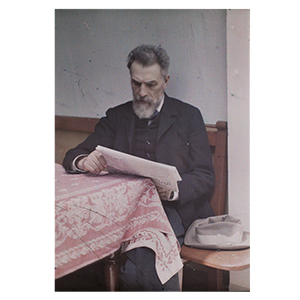

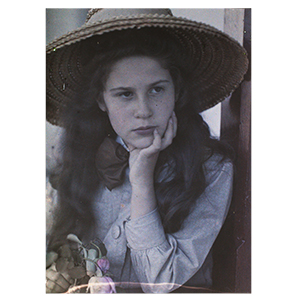

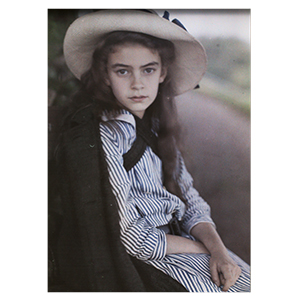

The international movement known as Pictorialism represented both a photographic aesthetic and a set of principles about photography’s role as art. Pictorialists believed that photography should be understood as a vehicle for personal expression on par with the other fine arts. Responding to both the new Kodak camera “snapshooters” and formulaic commercial photographers, the Pictorialists proudly defined themselves as true amateurs—those who pursued photography out of a love for the art.

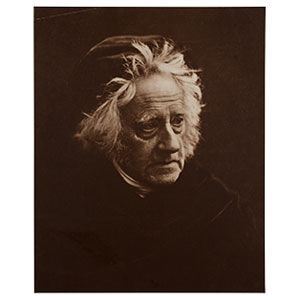

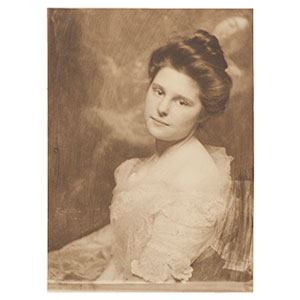

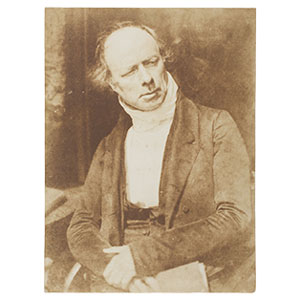

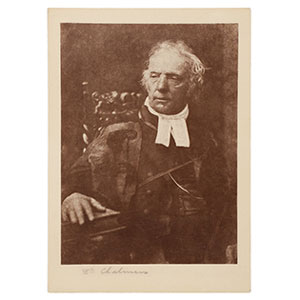

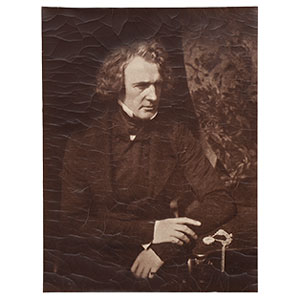

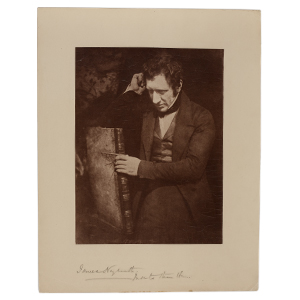

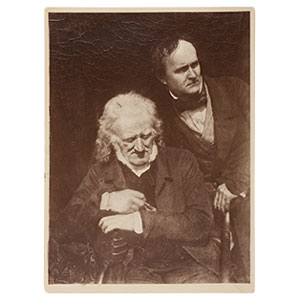

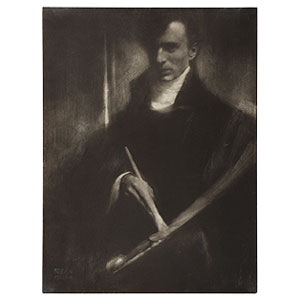

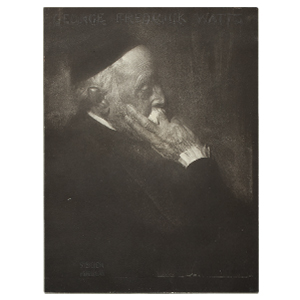

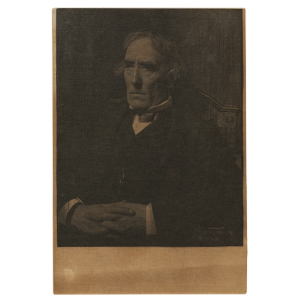

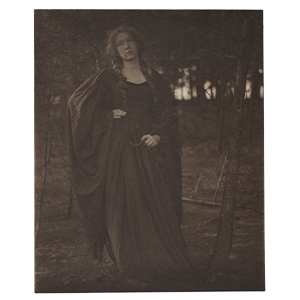

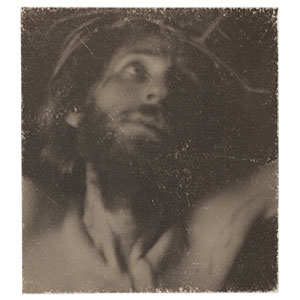

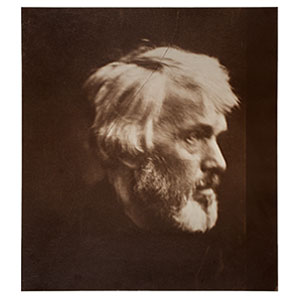

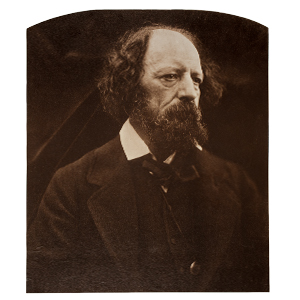

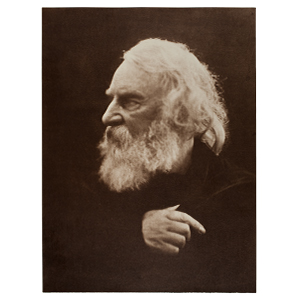

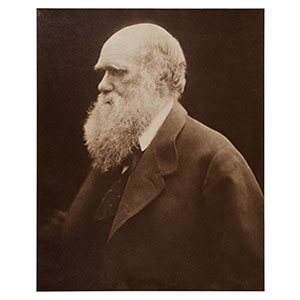

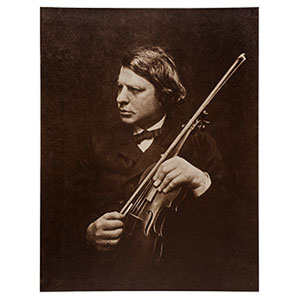

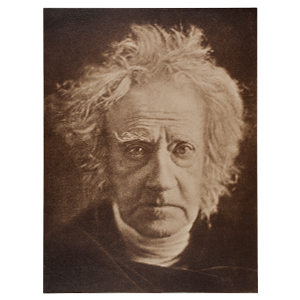

Pictorialism emerged toward the end of the nineteenth century and flourished for several decades thereafter. Inspired by the theories of such artists as Henry Peach Robinson (who advocated compositional techniques aligned with academic painting) and Peter Henry Emerson (who promoted naturalistic photography, with areas of diffused focus), Pictorialists also looked back to early photographers Julia Margaret Cameron and David Octavius Hill as touchstones.

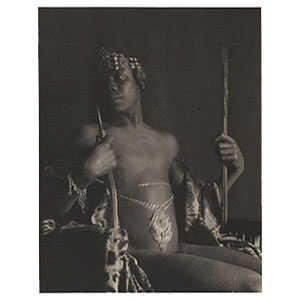

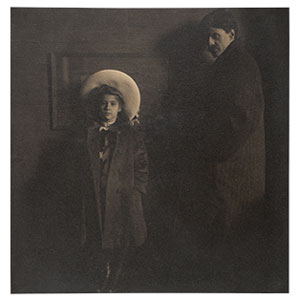

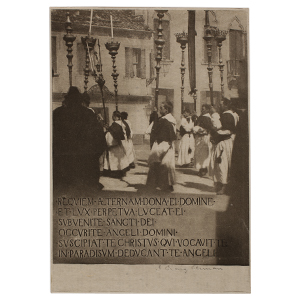

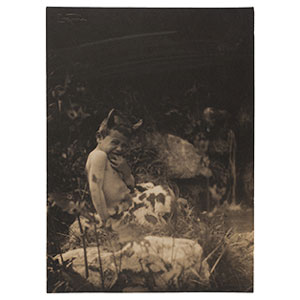

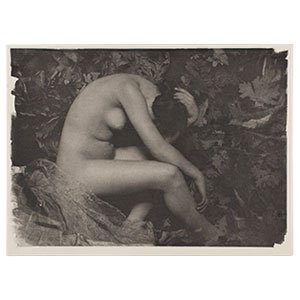

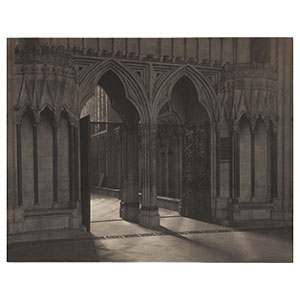

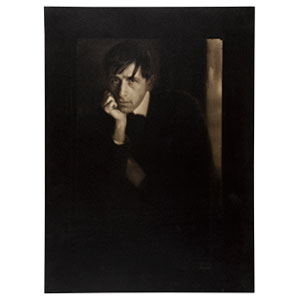

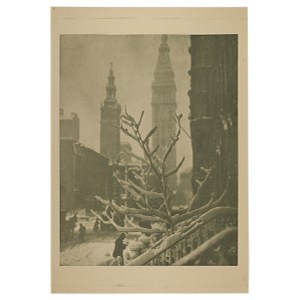

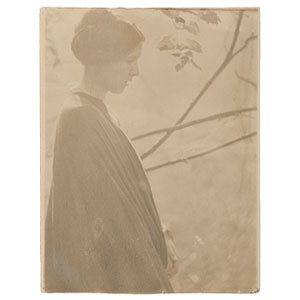

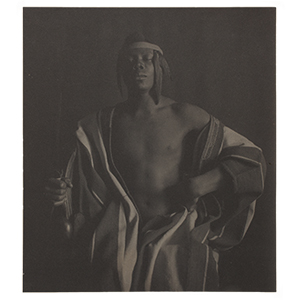

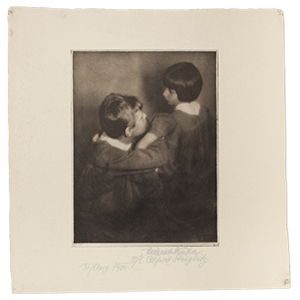

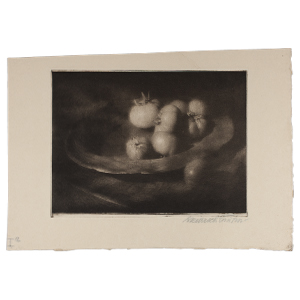

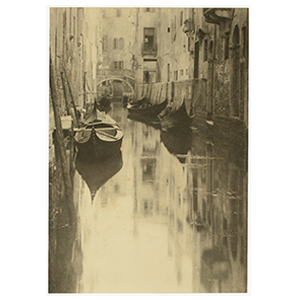

In order to further photography’s acceptance as an art, Pictorialists embraced the medium’s painterly qualities. They often preferred romantic or idealized imagery over the documentation of modern life, welcoming artistic composition and soft focus. They labored in the darkroom to produce unique works of art, employing time-consuming processes, such as gum bichromate printing and photogravure, that showed the artist’s hand. They cared greatly about how their work was presented, mounting their photographs on layers of tinted papers and advising on their framing and hanging in exhibitions.

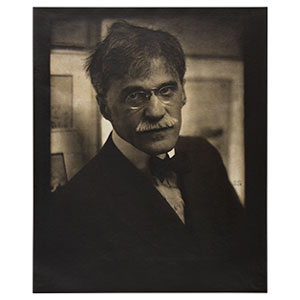

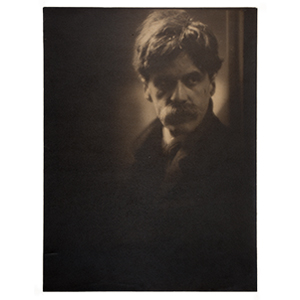

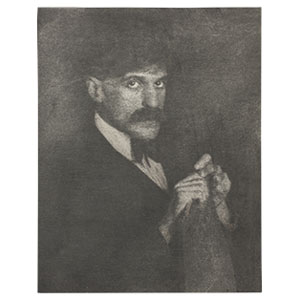

The movement comprised loosely linked camera clubs and societies in Europe, the United States, and Australia. Organizations such as the Brotherhood of the Linked Ring in England (founded 1892) and Alfred Stieglitz’s Photo-Secession in New York (formed 1902) mounted international salons and exhibitions, published portfolios and journals, and developed an influential aesthetic discourse about photography. The movement waned around the dawn of World War I—the Linked Ring disbanded in 1910, and Stieglitz, gravitating toward straight photography, published the last issue of his journal Camera Work in 1917—although smaller societies kept Pictorialist ideas alive through the 1930s.