Microscopy at The Art Institute of Chicago

|

|

|

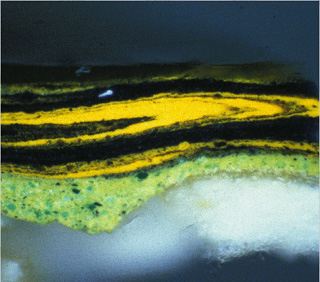

Detail (cross-section, dark field illumination)

The Poet’s Garden, 1888

Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853Ñ1890)

28 3/4 x 36 1/4 in.

Oil on canvas

Mr. amd Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn Memorial Collection, 1933.433 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

One of the research tools that museum conservation labs use is optical microscopy. Unlike X-radiography, which is a nonintrusive method for examining a work of art, optical microscopy often requires the conservator or microscopist to extract a sample of material from the edge of a work or from an existing area of paint loss. The excised paint sample permanently mounted on a slide and analyzed under a polarizing microscope, which reveals physical aspects such as color, size, and shape as well as optical characteristics such as refractive index of individual particles. Like all chemical compounds, each pigment has unique characteristics. Once the characteristics of an unknown pigment are determined, the microscopist may compare the sample to that of a known pigment. The conservation lab at the Art Institute has a library of over 1000 pigment reference samples, some of which are rare and no longer produced or used in painting. When a microscopist encounters an unknown pigment that is no longer commonly used, such as from a Medieval or Renaissance painting, the sample may be compared to one in the pigment library.

Sometimes works are sampled to determine how the paints are applied to the canvas or wood support. For an 18th-century painting by the artist Jean-Antoine Watteau entitled Fête Champêtre (1718/21), the microscopist took samples from the edges of the panel and already damaged areas and analyzed them under the microscope to see how the layers of paint were applied. This revealed a characteristic method of paint application used by this artist and helped to authenticate the work. The samples were also viewed under a Scanning Electron Microscope with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectrometry (SEM/EDS), which enabled the microscopist to create an elemental dot map. In this technique, a cross-section is coated with a thin layer of carbon (for conductivity) and placed in the microscope chamber. The instrument is set to scan for a particular element, such as lead, from which the common pigment lead white is derived. The microscope then detects a lead X-ray and maps the location from where it appears in the sample. The same cross-section can be scanned for other elements, such as iron, an ingredient in earth-toned pigments, or sulfur, an ingredient of a number of pigments including ultramarine blue. All of the information the microscope gathers is then combined, providing a visual diagram of the presence and distribution of elements in a work of art, and this information may be used to determine precisely which pigments are used in the work.

When the exhibition, Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Studio of the South, came to the Art Institute in 2001, conservators were able to initiate an enormous amount of research on the paintings to gain a deeper understanding of how these two artists worked. For example, from Vincent van Gogh’s painting The Poet’s Garden (1888) , a small paint sample was extracted from the yellow-green tree on the far right of the canvas. By looking at the cross-section of the sample, the microscopist could see the artist’s painting technique—that he painted “wet into wet,” quickly and without letting one layer of paint dry before he began to apply the next. This is seen in the swirling mixture of yellow and green colored layers, in the image above, that seem to flow into one another.

Several years ago, the microscopy lab at the Art Institute began researching the pigments in Georges Seurat’s famous Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte—1884. The primary goal of the examination was to determine the artist’s palette for this painting, which was completed in three stages. Even during the artist’s own lifetime, some of the colors in the composition began to change appearance. The investigation showed that the main pigment that has changed is zinc potassium chromate, or zinc yellow, which had a vibrant appearance when the artist applied it but darkened to a yellowish-brown soon after the painting was completed. In this work, Seurat used a technique called Pointillism, in which he placed small dots of color close together to blend in the viewer’s eye at a certain distance and create new colors. The effect of the zinc yellow darkening is that all of the colors created in combination with zinc yellow have darkened. The problem is that zinc yellow is not a stable pigment and has a tendency to alter its color, and this has changed the overall appearance of the painting. Because the painting is unvarnished (as originally preferred by Seurat and his contemporaries), conservators and curators have placed the work behind glass that blocks all ultraviolet light in order to provide better protection for the painting.

Adapted from a lecture given by Inge Fiedler.