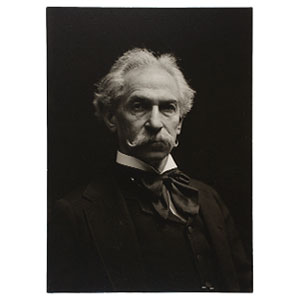

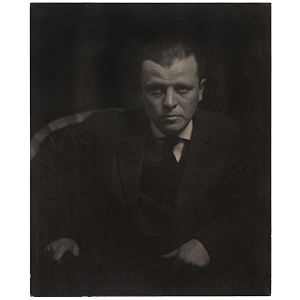

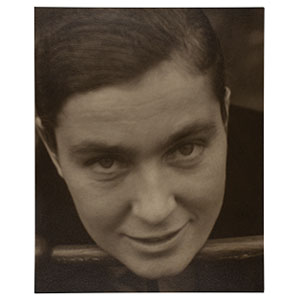

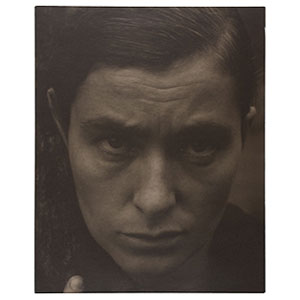

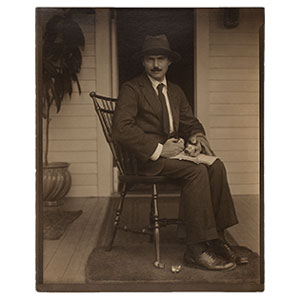

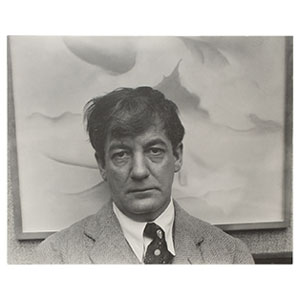

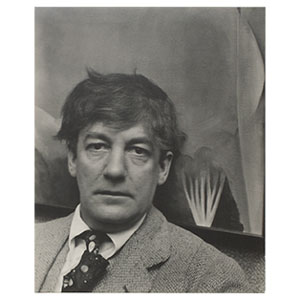

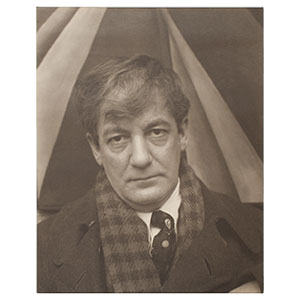

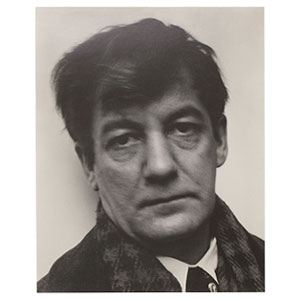

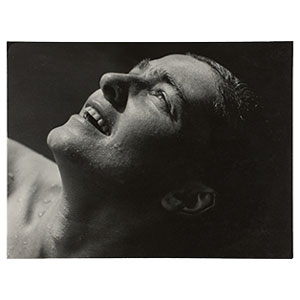

Alfred Stieglitz

American, 1864–1946

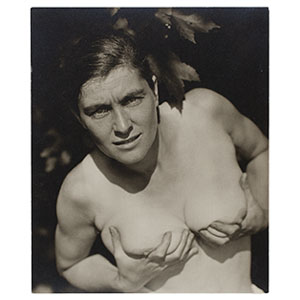

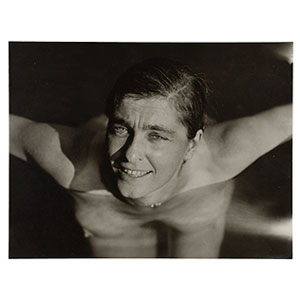

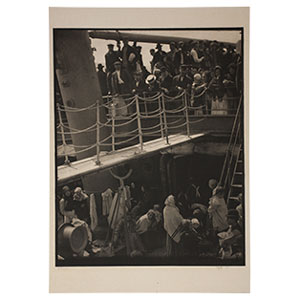

Through his own photographic work over the course of a half century, the journals he edited and published, and the exhibitions he mounted at his influential New York galleries, Alfred Stieglitz played a crucial role in establishing photography as an integral part of modern art in America. A founder of the Photo-Secession, a Pictorialist group of photographers, he elevated the discourse and practice of photography, forming key connections between American and European movements. Later, he embraced straight photography, linking its potential for modern expression with that of avant-garde painting and sculpture.

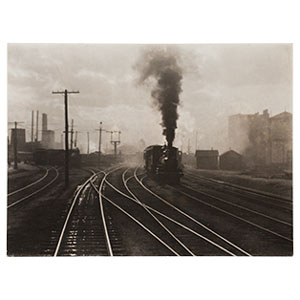

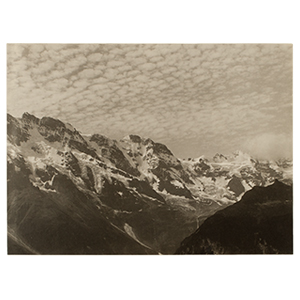

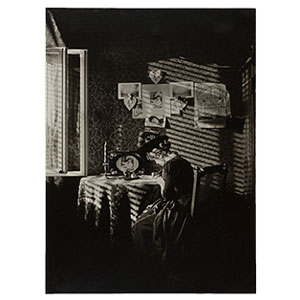

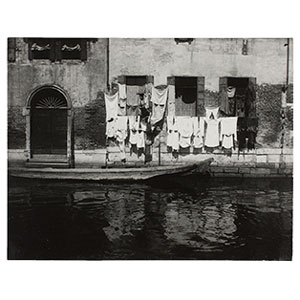

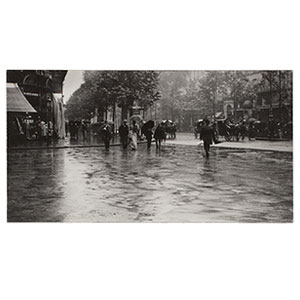

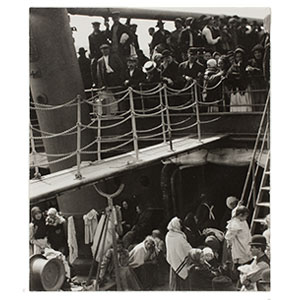

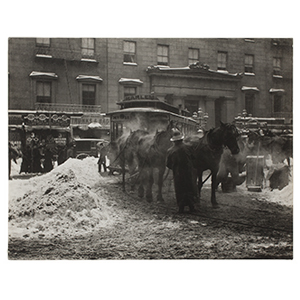

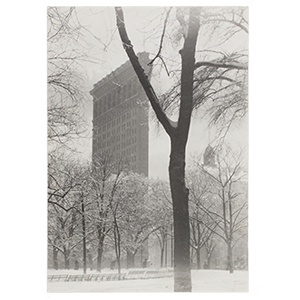

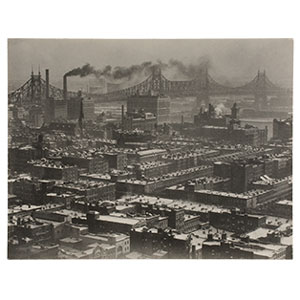

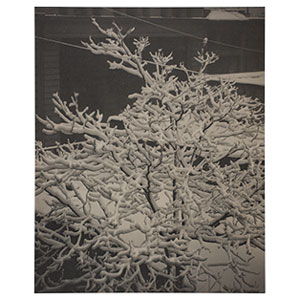

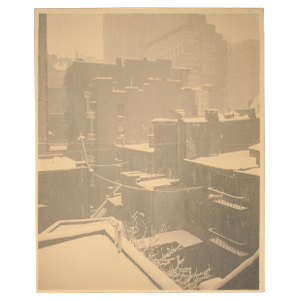

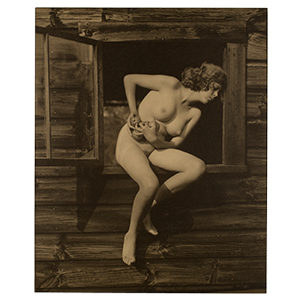

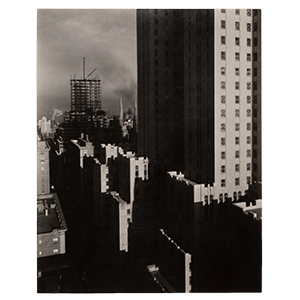

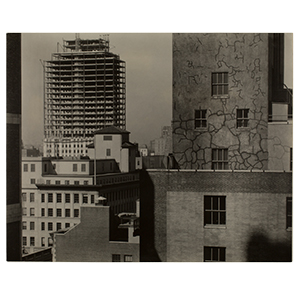

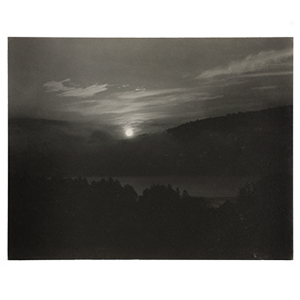

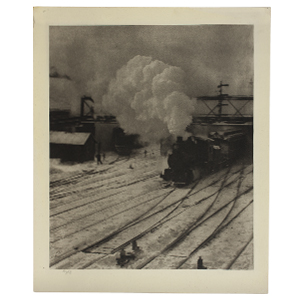

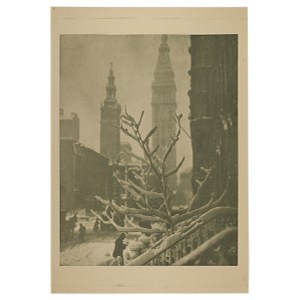

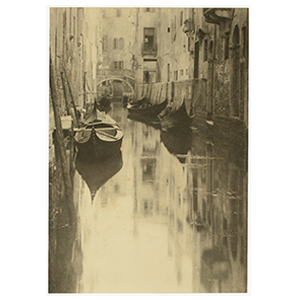

Stieglitz’s early photographs and writings served as arguments for photography’s acceptance as an art form on par with painting. Studying in Europe, he made picturesque scenes with great technical skill, winning prizes for his large carbon prints. Upon his return to New York, he turned his camera to the streets and buildings of that rapidly changing city, printing his images as photogravures in order to emphasize the atmospheric effects and lend them a softening tone.

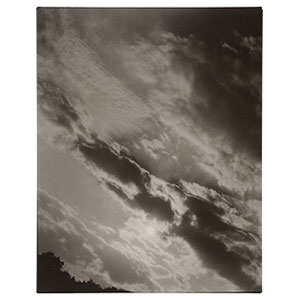

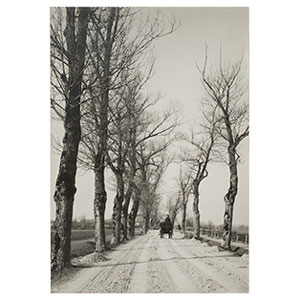

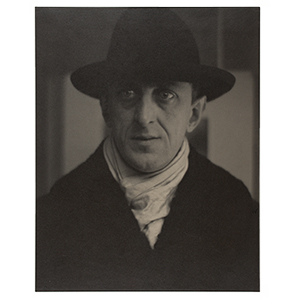

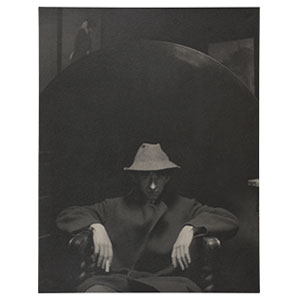

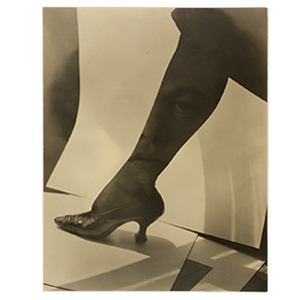

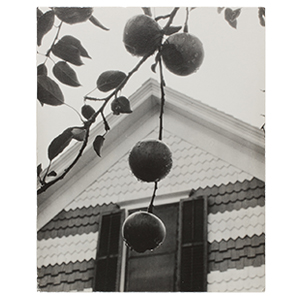

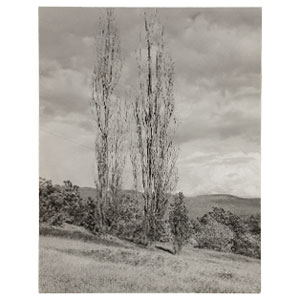

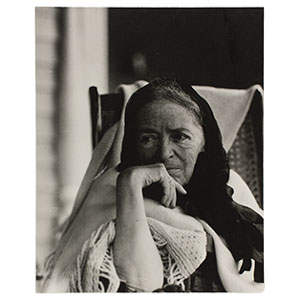

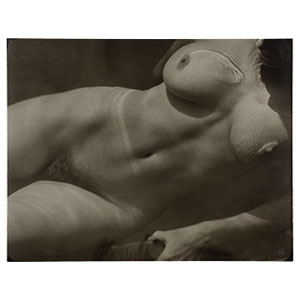

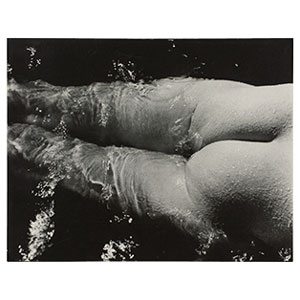

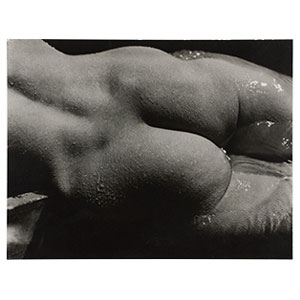

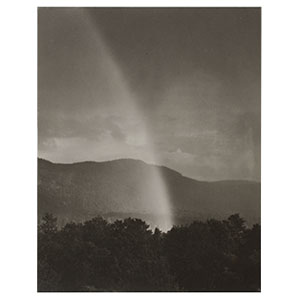

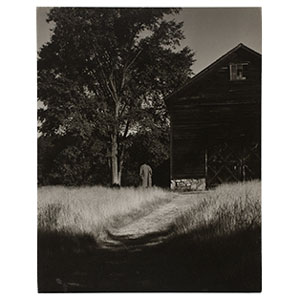

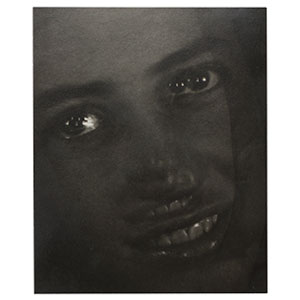

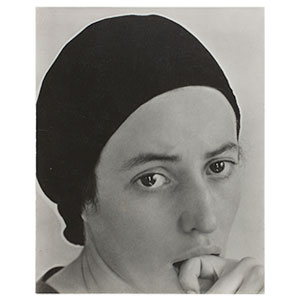

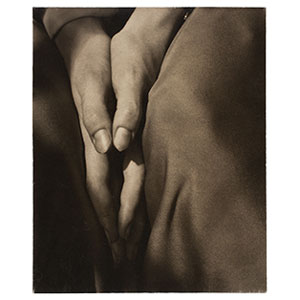

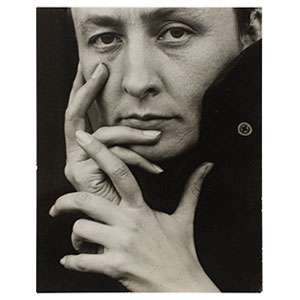

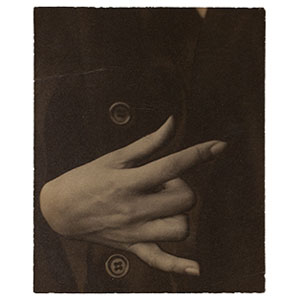

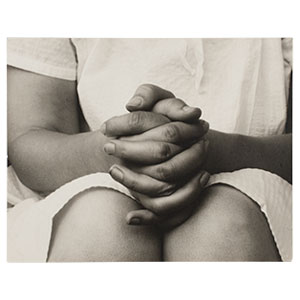

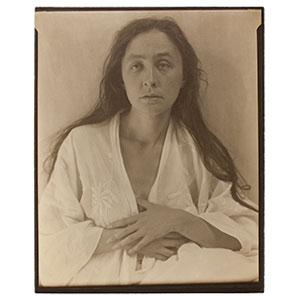

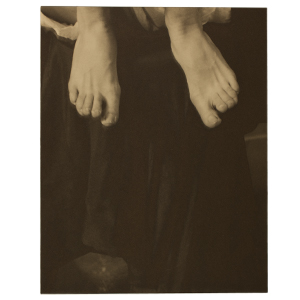

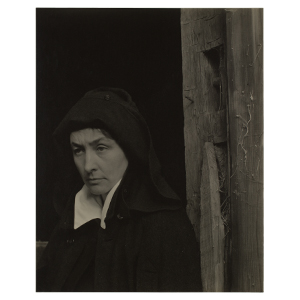

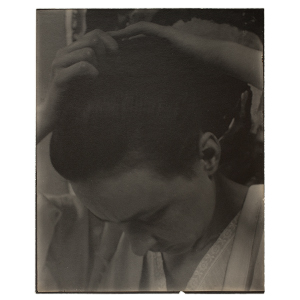

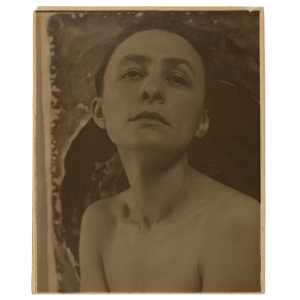

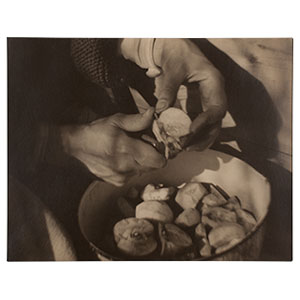

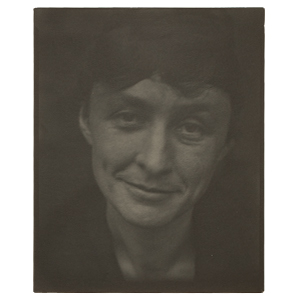

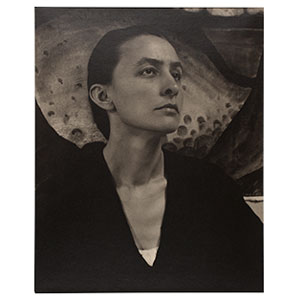

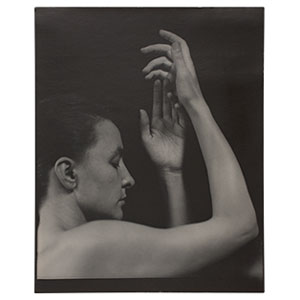

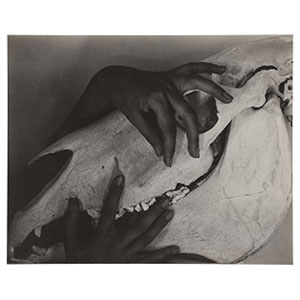

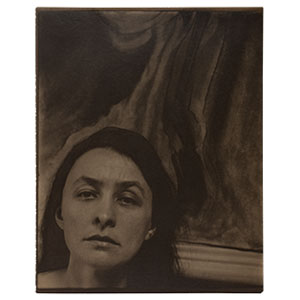

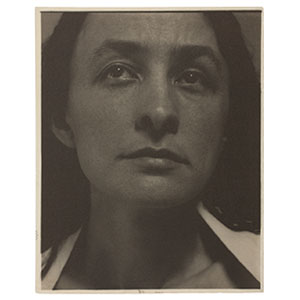

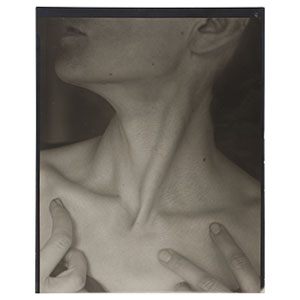

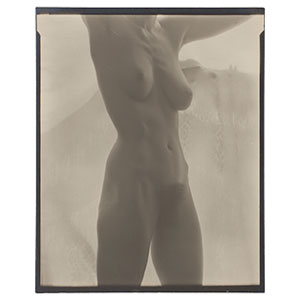

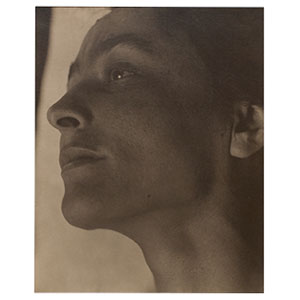

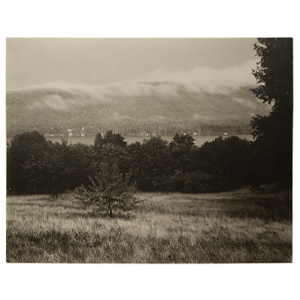

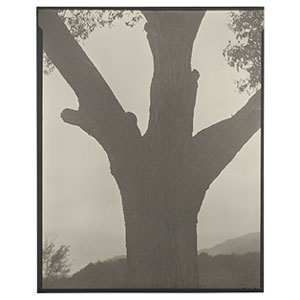

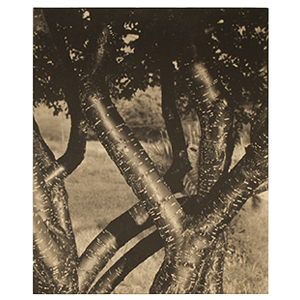

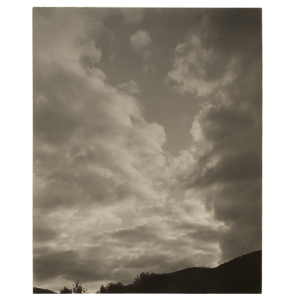

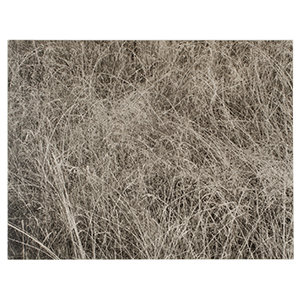

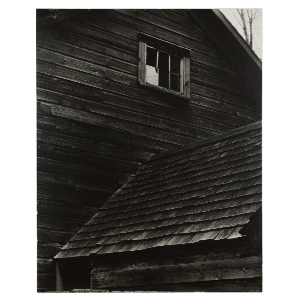

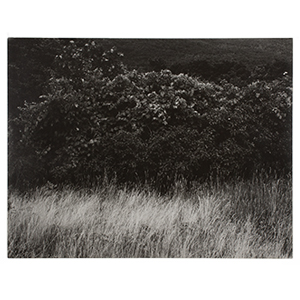

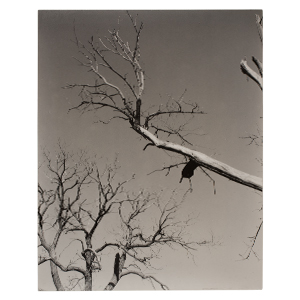

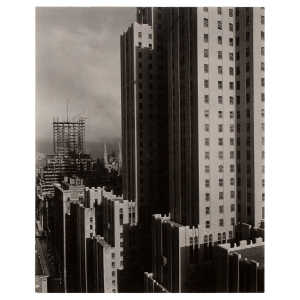

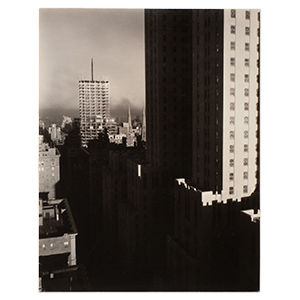

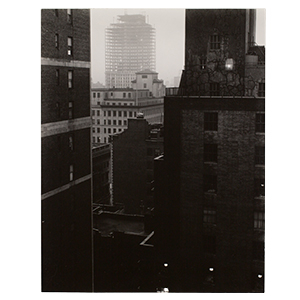

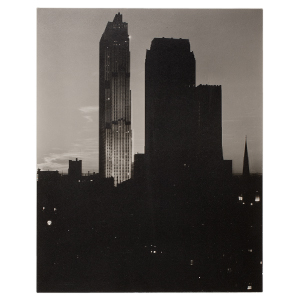

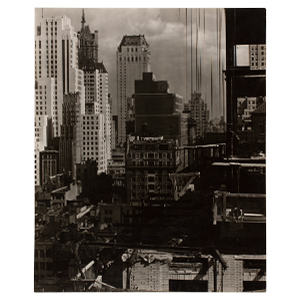

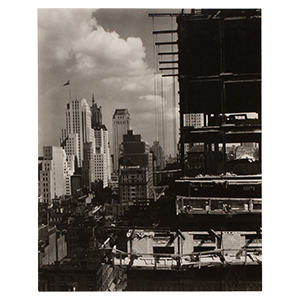

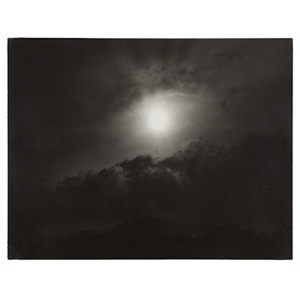

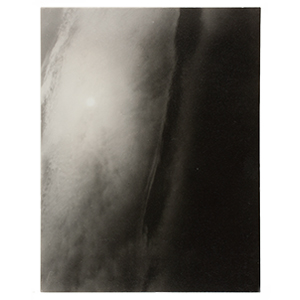

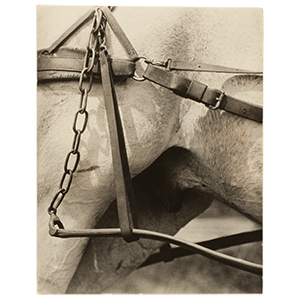

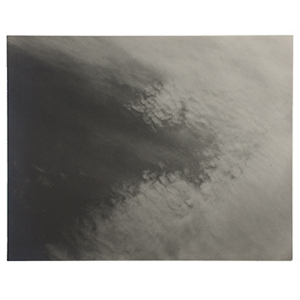

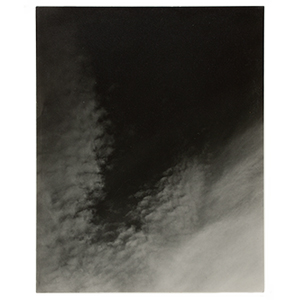

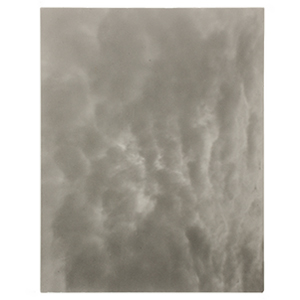

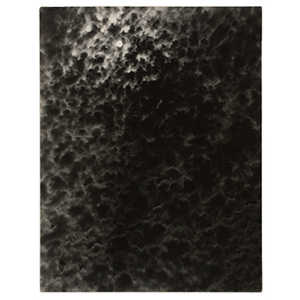

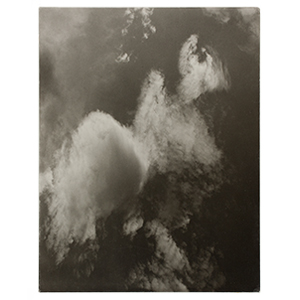

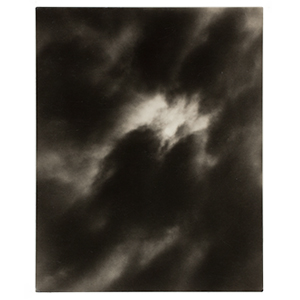

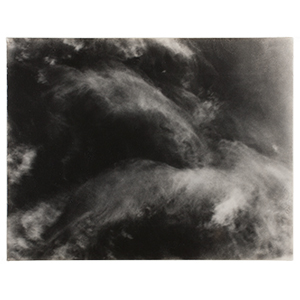

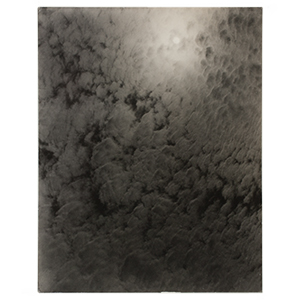

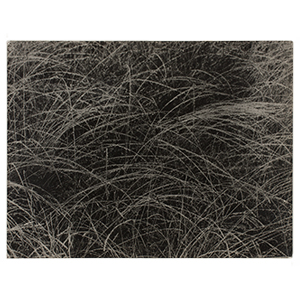

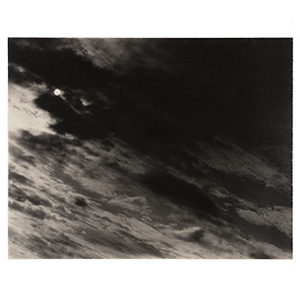

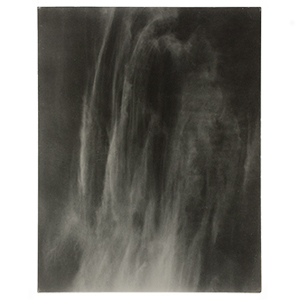

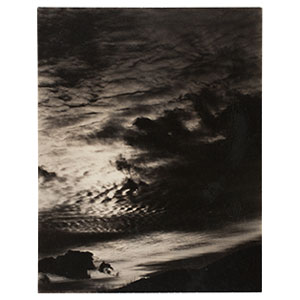

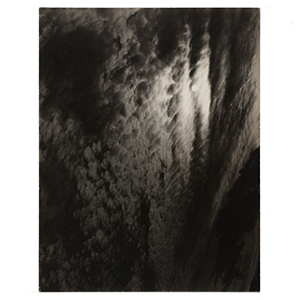

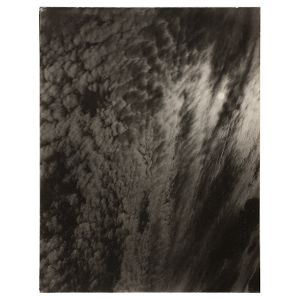

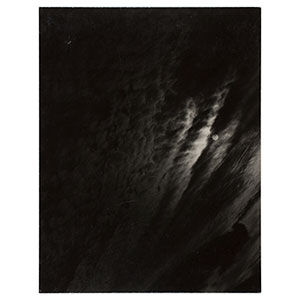

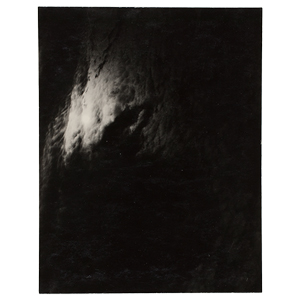

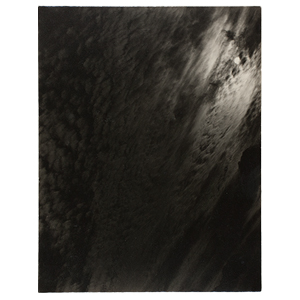

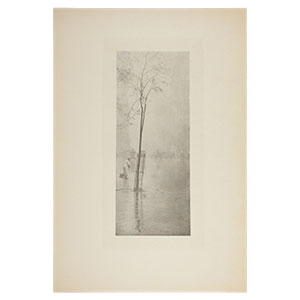

Beginning around 1910, Stieglitz shifted away from the painterly approach of the Pictorialists and toward a more direct, straightforward depiction, which was echoed in his use of photographic papers such as platinum, palladium, and later, gelatin silver prints. In his portraits of the many artists in his circle he probed new psychological depths, and an extended, “composite” portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe marked a new form of photographic description. Starting in 1922, Stieglitz made his first nearly abstract photographs with a series of cloud studies he called Equivalents, arguing that photography could assume the same nonrepresentational qualities as music. In his later work, he would continue to think in metaphors, whether depicting the construction of New York City skyscrapers or the dying poplars at his family estate in Lake George. Toward the end of his career, Stieglitz would revisit earlier negatives—reprinting and reinterpreting them with the crisp, cool tones of gelatin silver contact prints, demonstrating that his sensibilities had, even from the beginning, been thoroughly modern.

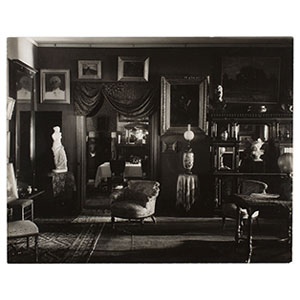

Stieglitz’s formidable activity as a publisher and a gallerist paralleled that of his work as an artist. After serving as the editor of Camera Notes, he published Camera Work, which evolved from a showcase for the Photo-Secession to a forum for international modern art of all media. At his galleries—the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known as 291; the Intimate Gallery; and An American Place—he introduced the European avant-garde and promoted a new generation of American painters, all while advocating for photography’s place among the other fine arts.