Many individuals were responsible for bringing the International Exhibition of Modern Art to Chicago. Serveral of the key players and their contributions are listed below.

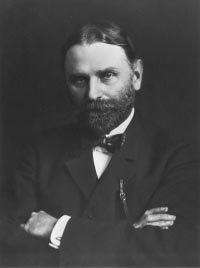

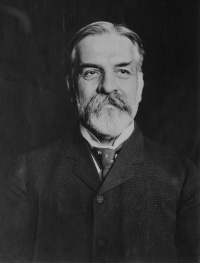

Arthur Taylor Aldis (1861–1933) was the individual most responsible for bringing the Armory Show to Chicago. An influential governing member of the Art Institute, he worked behind the scenes to garner interest and support for the controversial exhibition among the museum's trustees and the city's well-to-do.

Arthur Taylor Aldis (1861–1933) was a prosperous real estate developer and an influential governing member of the Art Institute of Chicago; he would eventually be elected trustee in 1916. He was introduced to Arthur B. Davies, president of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS), and Walt Kuhn, the group's executive secretary, in Paris in November 1912, when the two were in the midst of securing loans for the International Exhibition of Modern Art. "Rather wild and radical in his taste, and precipitate in his actions," according to Art Institute Director William M. R. French, Aldis immediately promised that the museum would host the exhibition following its run in New York.1 "We practically closed a deal with the Chicago Institute," Kuhn wrote to his wife, Vera, on November 11, 1912.2 At a time when powerful patrons held significant authority to shape the collections and exhibitions of American art museums, Aldis's support and influence with the museum trustees was crucial to bringing the Armory Show to Chicago. Throughout the official negotiations that ensued, Aldis maintained his own correspondence with Kuhn, keeping him abreast of the developments and offering advice about dealing with the more conservative museum officials. He was present at the signing of the contract in New York on February 28, 1913, and indeed, Kuhn recalled that it was "Mr. Aldis [who] came from Chicago with a committee to secure the show for the Art Institute"—although it was in fact Newton H. Carpenter, the museum's executive secretary, who served as the museum's official representative.3 As arrangements were confirmed and plans moved forward, Aldis continued to "butt in," as he called it, urging the museum staff to send the AAPS precise plans of the museum's galleries so that Davies and Kuhn could correctly lay out the exhibition in advance—he did "not suppose that any one here has a peculiar knowledge of the many modern schools which would enable us to do it."4 Particularly interested in the graphic arts, he and his wife, Mary, purchased three lithographs by Odilon Redon while the exhibition was still in New York. Through it all, Aldis remained the AAPS's "best man" in Chicago. "I am not exaggerating when I say," Kuhn wrote to him, "that it is largely owing to the moral support of persons like yourself that the success of the exhibition seems assured."5

1 French to Hallowell, Nov. 25, 1912. William M. R. French—Letter Books, box 16, vol. 1, 1912–13, Art Institute of Chicago Archives (hereafter called AIC Archives).

2 Walt Kuhn to Vera Kuhn, Nov. 11, 1912. Armory Show Records, Organizers' Letters, box 1, folder 4, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (hereafter called AAA).

3 Walt Kuhn, The Story of the Armory Show (New York, 1938), p. 19.

4 Aldis to Carpenter, Mar. 5, 1913. William M. R. French—Exhibition Correspondence, 1912–14, box 18, AIC Archives.

5 Kuhn to Aldis, Dec. 28, 1912. Armory Show Records, Traveling Exhibition, 1912–14, box 1, folder 61, AAA.

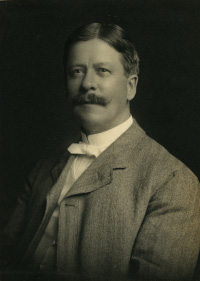

Newton H. Carpenter (1853–1918) was the executive secretary of the Art Institute and was responsible for the organizational details of mounting the Armory Show in Chicago. More a businessman than an art connoisseur, he welcomed the sensational exhibition primarily as a draw for increased attendance.

Newton H. Carpenter (1853–1918) was the executive secretary of the Art Institute of Chicago from 1881 to 1914. Following Director William M. R. French's preliminary negotiations, and especially after French left Chicago for a lecture tour of California, Carpenter stepped in to work out the details of bringing the Armory Show to Chicago. His extensive correspondence with Walt Kuhn, executive secretary for the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, reveals the minutia of arrangements for financing, shipping, insurance, installation, catalogue production, press coverage, and sales. As this record makes clear, Carpenter was—in the words of Art Institute governing member Arthur T. Aldis—"very keen" about the exhibition.1 His excitement, however, seems to have had less to do with his admiration for modern art than with his desire to take advantage of the unprecedented opportunity for increased publicity and attendance. In dealing with the press, Carpenter appears to have encouraged the satirical tone that characterized much of the city's coverage of the show. The Chicago Inter-Ocean quoted his rather wry comments extensively:

I can not describe myself as a cubist. . . . But I told one of the girls in the sculpture class that if she built a group of clay and let me stand off and hurl a brick at if for a while it would be a cubist piece of sculpture when I was through. As for the futurists? Well, I cannot say. But let me tell you this, that there are so many good pictures in that show that by the time you have looked at them all, you will forget the cubists, post impressionists and the vagueists—my own term—and remember good art only. It's to be a great show. The biggest thing Chicago has had this season.2

At the close of the exhibition, Carpenter was pleased not only with the record-breaking attendance figures but also with the cool reception the show received from the Art Institute's students, whom he had at first worried might be "side-tracked in some way by the exhibition."3 With no such immediate adverse consequences, he remained confident that the Art Institute had done right in bringing the Armory Show to Chicago. Writing to Kuhn, he pontificated, "I feel under great obligation to the Association for making this collection and for allowing it to come to Chicago. I say this, notwithstanding the adverse criticism which we have received on account of the exhibition. Our people have never waivered [sic] for a moment in the matter of having the exhibition here nor have they regretted it. We believe that what we have done has been for the best."4

1 Aldis to Davies, Mar. 17, 1913. Armory Show Records, Traveling Exhibition, 1912–14, box 1, folder 61, AAA.

2 "Hit Mud with Brick; Result, Cubist Art," Chicago Inter-Ocean, Mar. 9, 1913.

3 Carpenter to French, Apr. 7, 1913. French—Exhibition Correspondence, 1912–14, box 18, AIC Archives.

4 Carpenter to Kuhn, Apr. 21, 1913. Armory Show Records, Traveling Exhibition, 1912–14, box 1, folder 61, AAA.

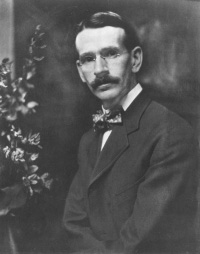

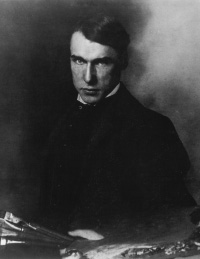

Arthur B. Davies (1862–1928) was the president of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors and was largely responsible for the inclusion of European modern artists in the Armory Show.

Arthur B. Davies (1862–1928) was a New York painter and president of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors. Although his own aesthetic was more conservative and rooted in the nineteenth century than that of the artists with whom he was affiliated, he was a passionate promoter of modern art. When a few friends had their artwork rejected from the National Academy of Design, a bastion of conservatism and the arbiter of taste in New York City, Davies joined their efforts to provide an alternative forum for modern artists. In December 1911, the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS) was founded, and on January 9, 1912, Davies was named its president. Almost immediately, the members of the AAPS began to make plans for what would become the Armory Show; although they had only vague notions of what would be displayed, they were determined that the show should reflect contemporary currents in art. In the summer of 1912, Davies came across a catalogue from that year's Sonderbund Exhibition in Cologne, which included the works of Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Edvard Munch, Pablo Picasso, and Vincent van Gogh. He wrote to Walt Kuhn, executive secretary for the AAPS: "I wish we could have as good a show."1

With an idea in mind of what artwork ought to be included, Davies sent Kuhn to Europe to meet with numerous artists, collectors, and dealers. Kuhn left in September 1912 for Germany and the Netherlands, and Davies joined him on November 6 in Paris. In order to gain access to the most avant-garde art in Europe, Davies recruited the help of his friend Walter Pach, an agent living in Paris with an intimate knowledge of the modern art scene. With Pach as their guide, Davies and Kuhn visited the studios of artists such as Constantin Brâncusi and Marcel Duchamp. Upon viewing Brâncusi's art for the first time, Davies remarked: "That's the kind of man I'm giving the show for."2 After leaving the home of art collector Michael Stein, where Davies had just arranged the loan of two paintings by Henri Matisse, he stood outside the closed door, doffed his hat, and bowed low as a gesture of gratitude to Stein. Remembering such signs of enthusiasm, Pach later noted that Davies was particularly quick to appreciate such art, which was unlike anything he had ever seen before: "Davies had not been in Paris for years and was seeing the moderns for the first time. The depth of his intuitions was therefore astonishing—in my experience, unique. He followed them up for years, in his own vigorous collecting and in the guidance he gave to numbers of other people. Modern Art in America owes more to him than to anyone else."3

At the end of November 1913, Davies returned to the United States to finalize the arrangements for the opening of the New York presentation. During this frenzied three-month period, Davies supervised all aspects of organization, including final negotiations with artists and lenders, extensive publicity, and the printing of catalogues and pamphlets. He was responsible for selecting American artists to participate. Davies also took the lead in corresponding with William M. R. French, director of the Art Institute, in order to arrange for the museum to host a smaller version of the Armory Show. Although he did not travel to Chicago, he was one of only two American artists to have multiple paintings exhibited in the Chicago presentation, a reflection of his invaluable role in organizing the exhibition.

1 Davies to Walt Kuhn, Sept. 2, 1912. Armory Show Records, Organizers' Letters, box 1, folder 1, AAA.

2 Walter Pach, Queer Thing, Painting: Forty Years in the World of Art (New York and London: Harper and Brothers, 1938), p. 178.

3 Pach to the director of Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, Jan. 14, 1958, published in Arthur B. Davies (1862–1928): A Centennial Exhibition (Utica, New York: Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, 1962), p. 7.

Arthur Jerome Eddy (1859–1920) was Chicago's boldest collector of modern art and a prominent supporter of the Armory Show. He was also the author of several books on art, most importantly Cubists and Post-Impressionism (1914),the first American publication to promote modern art. In addition to purchasing 18 paintings and 7 prints from the exhibition—making him one of the largest buyers—he also gave two popular lectures on Cubism at the Art Institute of Chicago at the time of the show.

Arthur Jerome Eddy (1859–1920) was a prosperous Chicago lawyer and progressive commentator on politics and economics, although he was especially renowned in the city for his many eclectic pursuits and his bold attraction to anything new—from bicycles and automobiles to the latest trends in modern art. Eddy had been a collector of James McNeill Whistler, Auguste Rodin, and the French Impressionists since the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893. By 1912, he had purchased his first abstract works by the American painter Arthur Dove and the Dutch painter Otto van Rees. As a resident of New York as well as Chicago, Eddy surely saw the dramatic press coverage leading up to the Armory Show's opening in New York, and this alone would have been enough to assure his attendance. In New York, Eddy purchased 15 of the most radical works on display, including Marcel Duchamp's Portrait of Chess Players (1911) and The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (1912), Albert Gleizes's Man on a Balcony (1912), and Francis Picabia's Dances at the Spring (1912). In Chicago, he purchased three additional paintings by the Spanish artist Amadeo de Sousa Cardoza, as well as three lithographs by Maurice Denis and four by Edouard Vuillard. Eddy's vanguard tastes were so well known that the Chicago press erroneously reported that he also purchased the most controversial picture in the Armory Show, the legendary Nude Descending a Staircase by Marcel Duchamp. Although he did not in fact buy the painting, Eddy did famously "find" the nude in the picture—her outline was published in the Chicago Daily Tribune on the day the exhibition opened in Chicago.

Possibly due to such activities as well as Eddy's bravado personality, Walt Kuhn, the executive secretary of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, at first considered him a great "source of annoyance."1 On the heels of the opening, Kuhn disparagingly complained to the association's president, Arthur B. Davies, that Eddy and others looked on the exhibition "in the usual 'Porky' parvenu manner," referring to Chicago's reputation as a city of stockyards and upstarts.2 Just a few days later, however, Kuhn changed his mind, writing, "Mr. Eddy has changed his tune. He gave a lecture Friday to about a thousand people in Fullerton Hall, endorsing the Association and asking fair play for the exhibitors."3 This lecture by Eddy on "The Cubists," delivered at noon on March 27, filled every seat of the museum's auditorium. According to the Chicago Examiner, he praised the radical artists, as well as, it seems, his own good sense in purchasing their works while they were still a bargain. Although the article criticized the collector for shying away from "the fatal moment of dealing seriously with Cubism" and indulging "in many moments of delightful persiflage," it also noted his evocative comparisons of the Cubist movement to the Progressive Party and of the appreciation of abstraction in painting to the enjoyment of color and design in Persian carpets.4 Eddy reprised his address on April 3, when he "referred repeatedly to the paintings as beautiful color conceptions" and once again "congratulated himself on having bought several of them."5

Eddy was not only an avid collector of and lecturer on modern art, he was also the author of several books on the subject. In 1902 he published his first book on art, Delight: The Soul of Art, and quickly followed that text with another, Recollections and Impressions of James A. McNeill Whistler (1903). Eddy's most important book and his great contribution to modern art scholarship is, however, Cubists and Post-Impressionism, which was inspired by the Armory Show; it was the first work published in the United States on modern art.6 In it, Eddy championed the vitality and invention of modernism, paying specific attention to Cubism and using many works from his own collection as examples.

1 Kuhn to Elmer MacRae, Mar. 25, 1913, quoted in Milton W. Brown, The Story of the Armory Show, 2nd ed. (New York: Abbeville Press, 1988), p. 208.

2 Kuhn to Davies, Mar. 26, 1913, quoted in ibid.

3 Kuhn to Davies, Mar. 29, 1913, quoted in ibid.

4 Joan Candoer, Chicago Examiner, Mar. 28, 1913.

5 "President Wilson a Cubist? Sure! Art Collector Says," Chicago Daily Tribune, Apr. 4, 1913, p. 9.

6 Although Eddy wrote Cubists and Post-Impressionism in 1913, it was not published until the following March.

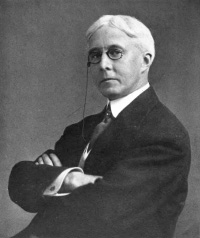

William M. R. French (1843–1914) was the director of the Art Institute at the time of the Armory Show. Although he was deeply skeptical of European modernism and initially reluctant to take on the exhibition, his commitment to the museum's progressive mission ultimately shaped the Chicago installation's greater focus on the most radical modern artists of the day.

William M. R. French (1843–1914) was the first director of the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as its curator of painting and sculpture, from 1885 until his death in 1914—just one year after the Armory Show opened at the museum. Then 69 years old, French was a respected art critic, lecturer, and teacher, with traditional personal taste. Deeply ambivalent about modernism, he wrote to Sara Tyson Hallowell, the Art Institute's buying agent in Europe, "I think I shall have to go out of the art critic business. I not only do not appreciate most of the Post-Impressionists' works, but a good deal of the Impressionists' work . . . although I know this is flat heresy."1 Informed of the planned International Exhibition of Modern Art by Art Institute Governing Member Arthur T. Aldis, whom he considered "rather wild and radical in his taste,"2 French nevertheless promptly initiated official negotiations with the Association of American Painters and Sculptors to bring the show to Chicago. After seeing the New York installation in mid-February, he described his impression of the show to Charles L. Hutchinson, president of the board of trustees: "The fraction of the exhibition comprising the real modernists—post-impressionists, cubists, pointillists, futurists—six or seven galleries, is eminently satisfactory. Anything more fantastic it would be hard to conceive."3 His skepticism prevailed, however, as he concluded:

I suspect we have here the representatives of two classes of radicals. First, a few eccentrics, some of them, like Van Gogh, actually unbalanced and insane, who really believe what they profess; secondly, the imitators, who run all the way from sheer weakness to the most impudent charlatanism. The choice is between madness and humbug.4

Despite such personal misgivings, French considered it the Art Institute's duty to encourage public awareness of and enthusiasm for art rather than legislate taste. To French, the International Exhibition of Modern Art was an opportunity to "give the radicals a fair chance" in the eyes of the public.5 With limited gallery space available for the exhibition, French specifically requested that the most radical foreign sections be sent intact, as these were the works that Chicago audiences would have the least chance of seeing otherwise. As has since become notorious, French left Chicago for a lecture tour on the West Coast four days before the exhibition opened. Although he did not exactly "flee" the city as the press enthusiastically reported (his plans having been made several months in advance), he was, by his own admission, relieved to be absent for the duration of the "freak exhibition."6

1 French to Hallowell, Mar. 18, 1913. William M. R. French—Letter Books, box 16, vol. 2, 1912–13, AIC Archives.

2 French to Hallowell, Nov. 25, 1912. William M. R. French—Letter Books, box 16, vol. 1, 1912–13, AIC Archives.

3 French to Hutchinson, Feb. 22, 1913. William M. R. French—Exhibition Correspondence, 1912–14, box 18, AIC Archives.

4 Ibid.

5 French to John W. Beatty, May 1, 1913. William M. R. French—Letter Books, box 16, vol. 2, 1912–13, AIC Archives.

6 French to Eugene Pirard, May 6, 1913. William M. R. French—Letter Books, box 16, vol. 2, 1912–13, AIC Archives.

Walt Kuhn (1877–1949) was a New York artist and the executive secretary of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors. He arrived in Chicago with the Armory Show, and his letters give a vivid, if biased, impression of the city's reaction to modern art.

Walt Kuhn (1877–1949) was a New York painter and illustrator and the executive secretary of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS). With the AAPS's European agent, Walter Pach, he helped to assemble the European section of the Armory Show during a month-long trip to Cologne, the Hague, Amsterdam, Berlin, Munich, Paris, and London in autumn 1912. Packed with visits to modern art exhibitions, artists' studios, galleries, and collectors' homes, the trip was a revelation for Kuhn, who was then working in an Impressionist style and was only slightly acquainted with the radical developments in European art. He felt that he had "crowded an entire art education into those few weeks."1

Upon returning to New York, Kuhn maintained an official correspondence with buyers, lenders, magazine publishers, and organizers in Chicago and Boston. It is, however, his personal letters to his wife, Vera, as well as to his good friend and president of the AAPS, Arthur B. Davies, that convey his most vivid impressions of the Chicago exhibition. Kuhn arrived in the city with the first shipment of pictures on the evening of March 21, 1913. In high spirits, he reported that Newton H. Carpenter, executive secretary of the Art Institute, had turned over the hanging to him without a single restriction, praised the professionalism of the staff, and approved the look of the exhibition—especially the Cubist room, which he said looked "simply great."2 Nevertheless, from the beginning his correspondence registers a deep prejudice against the "Porky" city of Chicago. Displeased with everything from the weather to what seemed to him to be cheap and gaudy hotels, Kuhn hoped to escape this "desert of vulgarity" as quickly as possible.3 To his dismay, however, he was obliged to spend two weeks correcting misinformation in the press and dealing with public officials and socialites. During his first contact with Chicago society at a dinner given by the Cliff Dwellers Society on March 23, Kuhn seems to have quarreled with collector Arthur Jerome Eddy and was relieved to have avoided the society's opening the next day. "The so-called intelligent class here," he wrote, "are a lot of self advertisers and ignoramuses. [Frederick James] Gregg and I are pretty well hated by one or two of them."4 His initial opinion of the general public who visited the museum was not much better, although he expressed a more positive view several days later, writing, "The visitors are becoming more and more interested, and the outlook now is very good as far as appreciation goes."5 Kuhn's greatest complaint, however, was the irreverent and sensational nature of the Chicago press. He conceded, "We made a big mistake by not being on hand here sooner than we were. The press had no idea of the importance of the show, they simply imagined it was a sort of circus."6

1 Kuhn to Pach, Dec. 12, 1912. Armory Show Records, Organizers' Letters, box 1, folder 7, AAA.

2 Kuhn to Vera Kuhn, Mar. 23, 1913. Armory Show Records, Organizers' Letters, box 1, folder 5, AAA.

3 Kuhn to Vera Kuhn, Mar. 1913. Armory Show Records, Organizers' Letters, box 1, folder 5, AAA.

4 Kuhn to Vera Kuhn, Mar. 25, 1913. Armory Show Records, Organizers' Letters, box 1, folder 5, AAA.

5 Kuhn to Vera Kuhn, Mar. 30, 1913. Armory Show Records, Organizers' Letters, box 1, folder 5, AAA.

6 Ibid.

Walter Pach (1883–1958) was the European agent for the Association of American Painters and Sculptors and was essential to the choosing and securing of the European works. As chief sales agent, he was also the spokesperson for the works in the galleries.

Walter Pach (1883–1958) was an American agent and artist who played an essential role in choosing and securing European artworks for the 1913 Armory Show. He served as the primary liaison between the artists, collectors, and dealers in Europe and the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS) in America. Working as an agent as well as a writer and lecturer on modern art, Pach traveled frequently to Europe and lived in Paris from the fall of 1907 until July 1908 and again from September 1910 until January 1913, right before the Armory Show opened in New York. During his time in Europe, he became an avant-garde art scene insider, developing close friendships with artists such as Constantin Brâncusi, Marcel Duchamp, and Henri Matisse. Pach was also close to many of the leading Parisian art collectors and dealers; he regularly visited the famous salons of Leo and Gertrude Stein and Sarah and Michael Stein.

Pach had been friends with Arthur B. Davies, president of the AAPS, since 1909. Davies had come to rely on him for news and information about modern European painters and would occasionally ask for small favors, such as translating articles or sending photographs. When Pach learned that Davies was organizing the Armory Show and intended to include European avant-garde art, he naturally offered to help his friend. Although he never formally joined the AAPS, he was instrumental in securing the loans of paintings, sculptures, and prints from European artists, collectors, and dealers. Davies and Walt Kuhn, executive secretary of the AAPS, joined Pach in Paris, where he escorted them to the galleries of Bernheim-Jeune, Eugène Druet, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, and Ambroise Vollard. He also brought them to the studios of artists such as Brâncusi and Duchamp. Pach's intimate knowledge of the Parisian art scene introduced Davies and Kuhn to art they might not have found otherwise but which perfectly suited their intentions for the Armory Show. At Brâncusi's studio, Davies remarked to Pach: "That's the kind of man I'm giving the show for."1 The artists visited and selected by the AAPS representatives were reflective of Pach's particular taste. Pach was responsible for selecting many of the most divisive and commented-on works featured in the Armory Show, such as Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, Matisse's Blue Nude, and Francis Picabia's Dances at the Spring.

Before they left Europe, Davies and Kuhn asked Pach to continue working with them in America as the AAPS's sales agent and spokesman, and in the meantime left it to him to make all the final arrangements in Europe, giving him "full authority to act for the Society."2 Although they left detailed instructions for what was to be included in the show, the availability of some works was uncertain until the last minute, so the choice of which works would be sent to the United States was ultimately left to Pach's discretion. He left Paris in order to work as the chief sales agent at the Armory Show, and in doing so became the exhibition's main spokesperson. Pach was the only person to be at the New York, Chicago, and Boston venues every day from the time the doors opened until the exhibition closed. In contrast to Kuhn's bleak account of the Chicago public, Pach seemed to take a much more good-natured view of the situation, perhaps because he seems to have genuinely enjoyed socializing with the people of Chicago. Pach reported to art collector Michael Stein, "You would be astounded at the amount of intelligence I find in my rounds of the galleries (I am chief salesman as you know),—even as a small fraction of the comment, it more than makes up for the idiots."3 One Chicago artist and buyer, Manierre Dawson, wrote an account that gives an impression of Pach's congenial methods: "The man with the moustache and tremulous hands who seemed in constant attendance saw me as the most lingering of spectators. Engaging me in conversation, I found him most interesting and informative. His name is Walter Pach."4

It was largely through Pach's efforts that some Chicagoans came to accept, and even appreciate, the art on view. Besides answering questions and providing his interpretations to visitors in the galleries, Pach gave a lecture on modern art in Fullerton Hall on March 24, the opening evening. In addition, he wrote several essays about the show: The Art of Odilon Redon; A Sculptor's Architecture; and "Hindsight and Foresight," "The Cubist Room," and "As to Futurists," all three published in the pamphlet For and Against; and translated Elie Faure's Cézanne. Pach was optimistic that the Armory Show and his efforts would have a significant influence on art appreciation among Chicagoans. He wrote to Robert Koehler, director of the Minneapolis School of Fine Arts, "I am full of confidence that the impression on all classes of the big public of Chicago has been a profound one and that it will continue to grow for many many years."5

1 Walter Pach, Queer Thing, Painting: Forty Years in the World of Art (New York and London: Harper and Brothers, 1938), p. 178.

2 Walt Kuhn to Theodore E. Butler, Dec. 21, 1912. Armory Show Records, Artists and Lenders Correspondence, box 1, folder 19, AAA.

3 Pach to Stein, Mar. 30, 1913. Gertrude Stein manuscript collection, quoted in Laurette E. McCarthy, "The 'Truths' about the Armory Show: Walter Pach's Side of the Story," Archives of American Art Journal, 44,3–4 (Fall 2004), p. 7.

4 Manierre Dawson, journal, Mar. 25, 1913. Manierre Dawson Papers, reel 64, frame 955, AAA.

5 Pach to Koehler, Apr. 26, 1913. Armory Show Records, Publicity, box 1, folder 52, AAA.