Of course in 1913 our exhibition was a "hard" one, and people were not prepared for it at all. Nevertheless I knew that we had sown a good seed and it is showing on the walls of the Institute. I am glad that Matisse is there, not as part of our harvest, but because I think there is really a good section of the American public that can keep up with modern art if given a chance.

—Walter Pach1

Almost a decade after the 1913 Armory Show, Walter Pach, the European agent for the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS), recognized the dual nature of the exhibition's public reception: despite inspiring much confusion, outrage, and ridicule, the Armory Show also inspired a significant number of Chicago artists and collectors to challenge the aesthetic status quo. The interest in modern art that the Armory Show had generated in the city would continue to grow over the years.

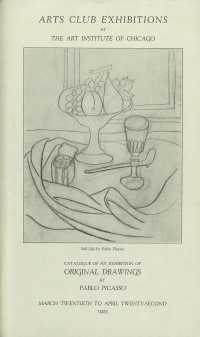

Following the exhibition, new art institutions were formed in Chicago to provide venues for presenting the work of modern European and American artists. In 1915, the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago was founded to promote the growth and understanding of contemporary art. Initially devoted to hosting lectures, the society started mounting exhibitions in 1918. Over the following decades, the Renaissance Society presented several exhibitions dedicated to artists who had been featured in the Armory Show, including Constantin Brâncusi, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso. Another venue, the Arts Club of Chicago, was founded in 1916 by Armory Show organizer Arthur T. Aldis, along with Rue Winterbotham Carpenter and several other prominent Chicagoans. The Arts Club was committed to exhibiting contemporary American and foreign artists. From 1923 to 1927, when its own galleries proved too small for its ambitious program, the club organized a series of shows at the Art Institute—including the first museum exhibition in the United States devoted to Pablo Picasso in 1923 and an exhibition on Georges Braques in 1924.

Although the Renaissance Society and Arts Club supported the work of American artists, the opportunities for emerging Chicago modernists were still limited. The main opportunity for living artists to exhibit their work in the city, the Art Institute's annual Chicago and Vicinity show, was juried by the conservative Chicago Society of Artists. In 1921, after a particularly harsh year, however, artists Carl Hoeckner, Raymond Jonson, and Rudolph Weisenborn organized a "salon des refusés" of nearly 300 works at Rothchild's department store on State Street. The following year, they formed the Chicago No-Jury Society of Artists and began to hold independent shows at such venues as Marshall Field's department store. With an abstract emblem and events like the Cubist Balls of 1923–25, these artists clearly looked to the Armory Show as a source of inspiration.

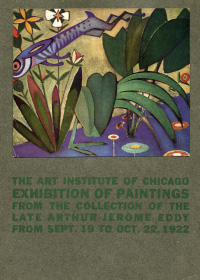

Private collectors were also spurred on by the exhibition. Arthur Jerome Eddy, for example, was one of the foremost patrons of modern art in the city. Having acquired some of the most radical works in the Armory Show, he continued to augment his collection and to promote modern artists in the public eye. He wrote the ambitious and heavily illustrated Cubists and Post-Impressionism (1914), the first book on the subject published in the United States. By the time of Eddy's death in 1920, his collection had swelled to include hundreds of works. With the support of fellow Armory Show veteran Arthur T. Aldis, 67 of these were exhibited at the Art Institute in 1922, and 23 were eventually acquired for the museum's collection.

By the early 1920s, a number of Chicagoans were following Eddy's example and buying works of modern art. The most notable of these collectors were Frederic Clay Bartlett and his second wife, Helen Birch Bartlett, who amassed an important collection of Post-Impressionist and modern French art. Their collection, which included works by Matisse, Picasso, and other artists whose work had been presented at the Armory Show, was displayed at the museum three times in the 1920s. In 1926, following the untimely death of Helen Birch Bartlett, the collection was donated to the Art Institute, making it the first museum in America to own a significant collection of modern art that was permanently on view. An Art Institute trustee since 1918, Robert Allerton was another local collector and generous donor, giving nearly 900 works of art to the museum over the course of his lifetime. Some of Allerton's earliest acquisitions, Sketches of a Young Woman and a Man and Seated Male Nude by Picasso, became the museum's first works by the artist in the permanent collection when donated in 1923 and 1924, respectively.

The particularly generous spirit of its patrons allowed the Art Institute to continually expand its holdings of modern art. In 1921, Joseph Winterbotham, father of Arts Club of Chicago founder Rue Winterbotham Carpenter, established a fund for the purchase of modern art with some unusual but bold conditions. With an initial gift of $50,000, Winterbotham stipulated that the money must be invested and, with the earned interest, the museum should build a collection of 35 European modern paintings. Once the first group of 35 was assembled, any of these artworks could later be sold or exchanged for other modern works. Winterbotham's goal was to ensure that the development of the collection "as time goes on, is toward superior works of art and of greater merit and continuous improvement."2 The first purchase made with the fund was a painting by Matisse, who had been the object of such derision and protest in 1913.3 Winterbotham's dedication to enriching the Art Institute's modern art collection set an example that other Chicagoans soon followed.

Among the museum's own staff, the momentum generated by the Armory Show seemed to initially stall: an exhibition of modern German art, for example, planned in 1914 and spearheaded by Arthur T. Aldis, was cancelled. After the end of World War I, however, and with the appointment of confirmed modernist Robert Harshe as assistant director in 1920 and as director the following year, the Art Institute made a series of groundbreaking acquisitions. By 1933, when the museum mounted the huge Century of Progress exhibition celebrating Chicago's centennial, the works of Matisse, Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Vassily Kandinsky, and others figured as the culmination in a chronological arrangement of artworks—echoing their importance at the Armory Show in 1913. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the next generation of museum staff built and expanded on this legacy. Under the leadership of Director Daniel Catton Rich and Katharine Kuh, the museum's first curator of modern painting and sculpture, the collection of modern art continued to grow through bold acquisitions, such as Matisse's Bather by a River. As a result of this continued dedication, the museum's remarkable collection of modern art became one of its defining features.

This momentum continues to the present day. Indeed, while a century ago the Art Institute of Chicago made seven crammed galleries available for a limited presentation of what Walt Kuhn called "the new spirit in art," today the museum boasts numerous spaces to see art of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, including Renzo Piano's Modern Wing.4

1 Walter Pach to Rue Carpenter, May 14, 1922. Arts Club Papers, The Newberry Library.

2 Joseph Winterbotham Deed of Gift to the Art Institute of Chicago, Apr. 9, 1921. AIC Archives.

3 Sophia Shaw Pettus, "Checklist of the Joseph Winterbotham Collection, 1921–1994," Museum Studies, 20, 2 (Fall 1994), p. 183.

4 Kuhn to Walter Pach, Dec. 12, 1912. Armory Show Records, Organizers' Letters, box 1, folder 7, AAA.