Unlike the New York catalogue for the International Exhibition of Modern Art—which, due to time constraints and a staggering number of artworks, was awkwardly organized and included a supplement with corrections and late additions—the catalogue for the Chicago exhibition had the advantage of being published in one compact volume with 16 illustrations and 453 items organized alphabetically by artist.1 For the benefit of the public and at the insistence of the Art Institute's director, William M. R. French, the titles of all the works were also translated into English.

Like the New York publication, the Chicago catalogue included a preface by Frederick James Gregg, a newspaperman who served as the publicity representative for the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS). Gregg quoted a lengthy statement by Arthur B. Davies, the AAPS president, explaining the exhibition's intention to simply give "the public here the opportunity to see for themselves the results of new influences at work in other countries in an art way" so that "the intelligent may judge for themselves."2 This comment was popular with the Chicago press and in keeping with the widely accepted mission of the museum. Less often repeated, and indeed removed from later printings of the catalogue, were Gregg's much more assertive comments regarding the need for change, progress, and bravery in American art along the lines of the modernist innovations in Europe. "The less they find their work showing signs of the developments indicated in the Europeans," he wrote, "the more reason they will have to consider whether or not painters and sculptors here have fallen behind through escaping . . . the forces that have manifested themselves on the other side of the Atlantic."3

Click the above images to download a PDF of the original documents

In addition to the exhibition catalogue, visitors could also purchase an array of publications on modern art as they entered the exhibition. The AAPS produced four pamphlets to sell at the New York presentation, three of which were also sold in Chicago: Odilon Redon by Walter Pach (the AAPS European agent), Cézanne by Elie Faure (translated by Pach), and A Sculptor's Architecture by Pach.4 In addition, the Art Institute and the AAPS produced a pamphlet especially for Chicago audiences that presented both positive and negative assessments of the exhibition. Entitled For and Against, the 64-page booklet included Davies's statement regarding the exhibition's objective (without Gregg's more decisive comments); articles by Pach and Gregg defending the exhibition; a reprint of an open-minded review from the Chicago Evening Post; two negative reviews by noted artist and critic Kenyon Cox and Princeton art historian Frank Jewett Mather; and an article on Cubism by artist Francis Picabia. According to Newton H. Carpenter, the museum's executive secretary, this pamphlet sold extremely well.

Alongside these "official" publications, the Art Institute also sold a number of magazines with special articles on the exhibition, including the March 1913 issue of Arts & Decoration, which was edited by AAPS member Guy Pène du Bois and devoted entirely to the Armory Show, and the April issue of Art and Progress, which included a deeply critical article by Adeline Adams.5

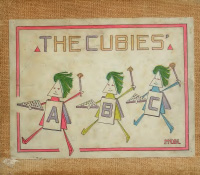

Even after the Armory Show closed, the exhibition continued to inspire texts. One amusing example is The Cubies' A B C, a satire of modern art, personified as three geometric figures. The book was the creation of Mary Mills and Harvey Lyall, who dedicated it to the AAPS. Written in the style of a children's ABC book, the letters are accompanied by rhyming descriptions of the qualities of modern art that are paired with illustrations, some of which include works from the Armory Show. The Art Institute's Head of a Woman (Fernande) by Pablo Picasso, for example, is featured in the book, paired with the following verse:

P's for Picasso, Picabia and Party

(Who deal in abstractions, distractions and such.)

When with vision chaotic and expletives hearty,

You beg of a Cubie their sense to impart, he

Profoundly makes answer: "In little is much."

—P's for Picasso, Picabia and Party.6

1 While the checklist included 453 works, because groups of an artist's prints or drawings were listed together under single entries, the total number of works exhibited was actually 634: 312 paintings, 57 watercolors, 120 prints, and 115 drawings.

2 Association of American Painters and Sculptors, Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Modern Art, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute, 1913).

3 Ibid.

4 A collection of excerpts from Paul Gauguin's Tahitian journal Noa-Noa (translated by Walt Kuhn) was not sold on grounds of indecency. Two weeks before the exhibition opened in Chicago, French, the Art Institute director, received a letter from Adeline Adams, a New York acquaintance, making him aware of the illicit pamphlet. Adeline Adams to William M. R. French, Mar. 13, 1913. French—Exhibition Correspondence, box 18, 1912–14, AIC Archives.

5 Carpenter wrote to French during the latter's lecture trip in California, "I was quite amused over the article in Art and Progress. Miss Mechlin sold me the 500 copies without my seeing the article. However, these magazines have sold so well that we have ordered 465 additional copies. We get them for 7 ½¢ and sell them for 20¢ each." Carpenter to French, Apr. 7, 1913. William M. R. French—Exhibition Correspondence, 1912–14, box 18, AIC Archives.

6 Mary Mills Lyall and Harvey Lyall, The Cubies' A B C (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1913), p. 36.