The Photo-Secession

Founded 1902

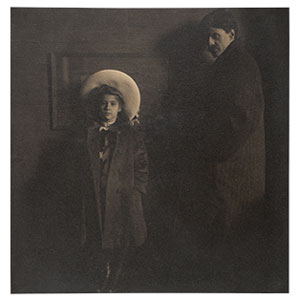

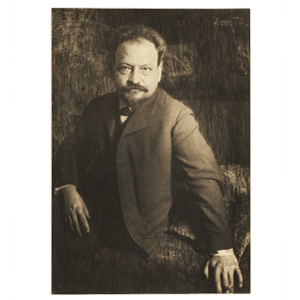

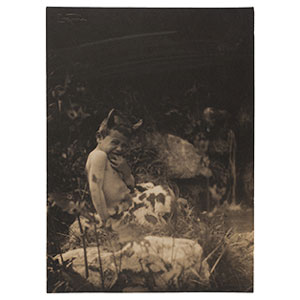

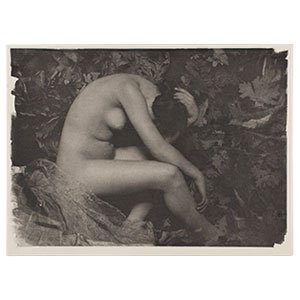

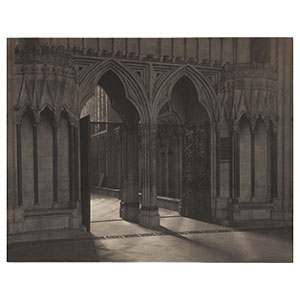

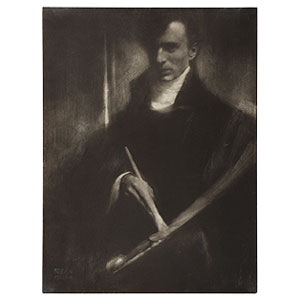

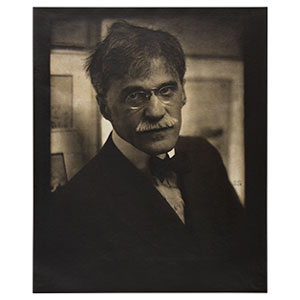

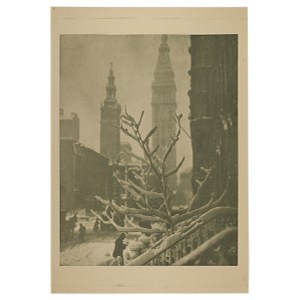

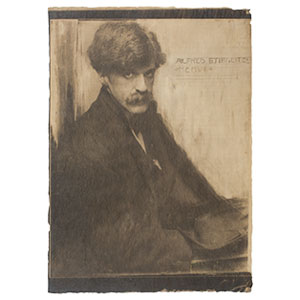

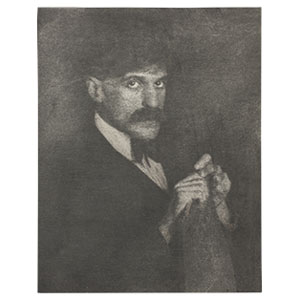

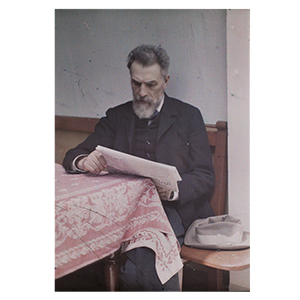

Following the model of other artistic secessions in Europe around the turn of the century—notably that of the Brotherhood of the Linked Ring, an English society of Pictorialist photographers that counted Stieglitz and many in his circle as members—Stieglitz formed the Photo-Secession in 1902. Along with other artists he felt were advancing the artistic acceptance of photography, Stieglitz decided to “secede” from the accepted ideas, promulgated by many camera clubs, of what constituted a successful photograph.

He outlined the terms of the Photo-Secession in a statement published in 1903:

Its aim is loosely to hold together those Americans devoted to pictorial photography in their endeavor to compel its recognition, not as the handmaiden of art, but as a distinctive medium of individual expression. The attitude of its members is one of rebellion against the insincere attitude of the unbeliever, of the Philistine, and largely of exhibition authorities. The Secessionist lays no claim to infallibility, nor does he pin his faith to any creed, but he demands the right to work out his own photographic salvation.[1]

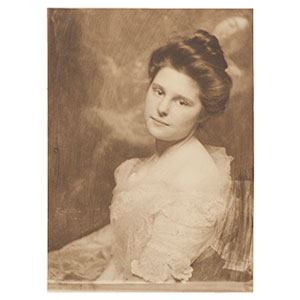

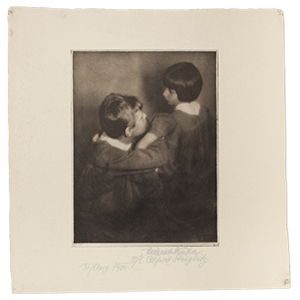

Unlike the amateur camera clubs of the time, the Photo-Secession did not select its members through an official election or board—rather, inclusion relied upon a mutual feeling of belonging and, of course, Stieglitz’s approval. Stieglitz recalled many years later Gertrude Käsebier’s asking if she was a Photo-Secessionist, to which he replied that if she felt she was, “that’s all there is to it.”[2] With the exception of F. Holland Day, who refused the invitation, nearly all of Stieglitz’s photographer colleagues joined the Photo-Secession. Stieglitz published photographs by the group in Camera Work and exhibited works at the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession (later known as 291). He also oversaw the Photo-Secession’s participation in national and international photography salons, submitting the “loan collection of the Photo-Secession”—a representative group of work selected by Stieglitz—for exhibition with the stipulation that all works must be accepted for display.

[1] Alfred Stieglitz, “The Photo-Secession,” in Bausch and Lomb Lens Souvenir (Rochester, New York: Bausch and Lomb Optical, 1903); reprinted in Richard Whelan, ed., Stieglitz on Photography: His Selected Essays and Notes (Aperture, 2000), p. 154.

[2] Alfred Stieglitz, “The Origin of the Photo-Secession and How It Became 291,” Twice a Year 8–9 (1942); reprinted in Whelan, Stieglitz on Photography, p. 120.