-

Timothy O’Sullivan, Historic Spanish Record of the Conquest, South Side of Inscription Rock, N.M. — No. 3, 1873

Timothy O’Sullivan, Historic Spanish Record of the Conquest, South Side of Inscription Rock, N.M. — No. 3, 1873 -

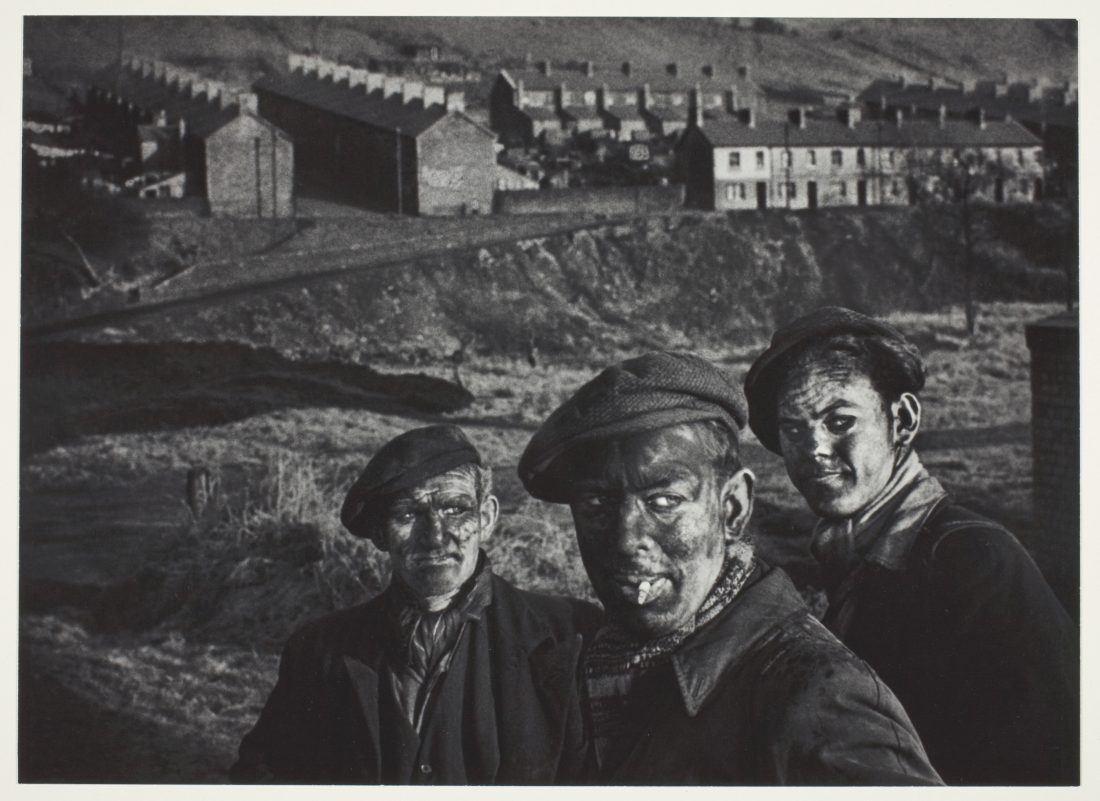

W. Eugene Smith, Three Generations of Welsh Miners, 1950. © Estate of W. Eugene Smith/Kevin Smith

W. Eugene Smith, Three Generations of Welsh Miners, 1950. © Estate of W. Eugene Smith/Kevin Smith -

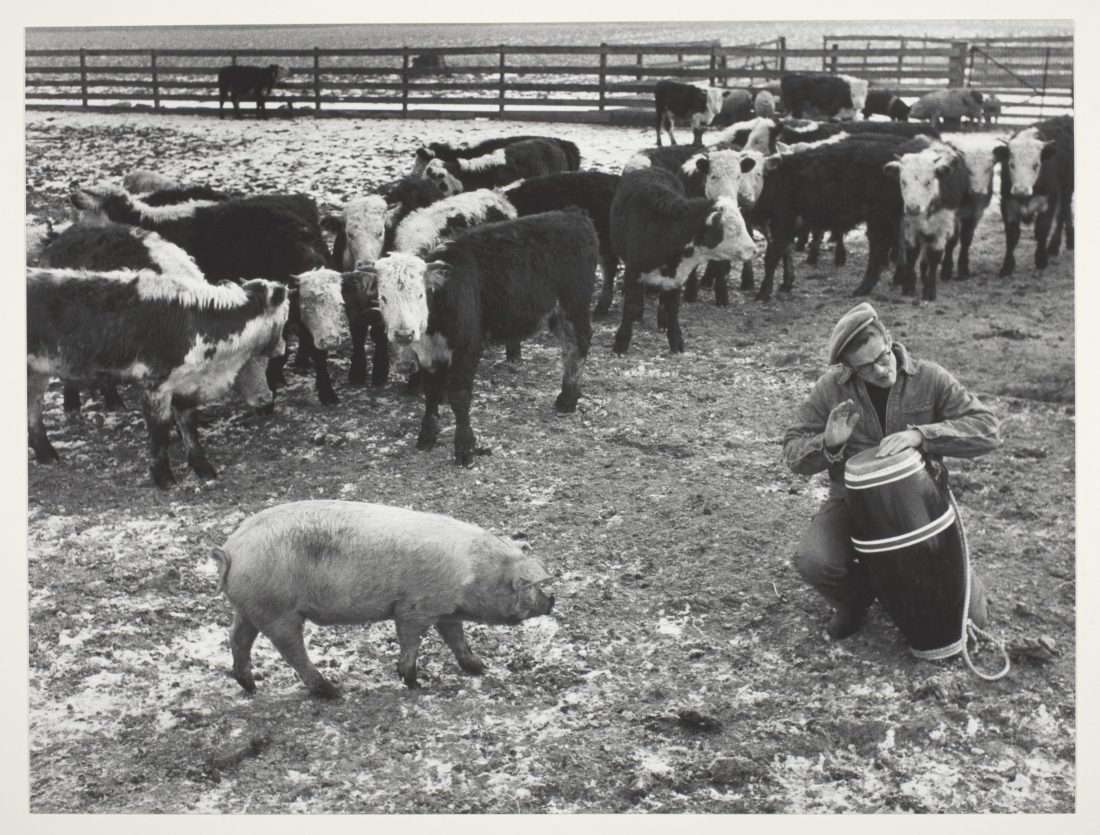

Dennis Stock, Jimmy Beating Bongo Drums for Farm Animals, 1955. © Magnum Photos, Inc. and Dennis Stock

Dennis Stock, Jimmy Beating Bongo Drums for Farm Animals, 1955. © Magnum Photos, Inc. and Dennis Stock -

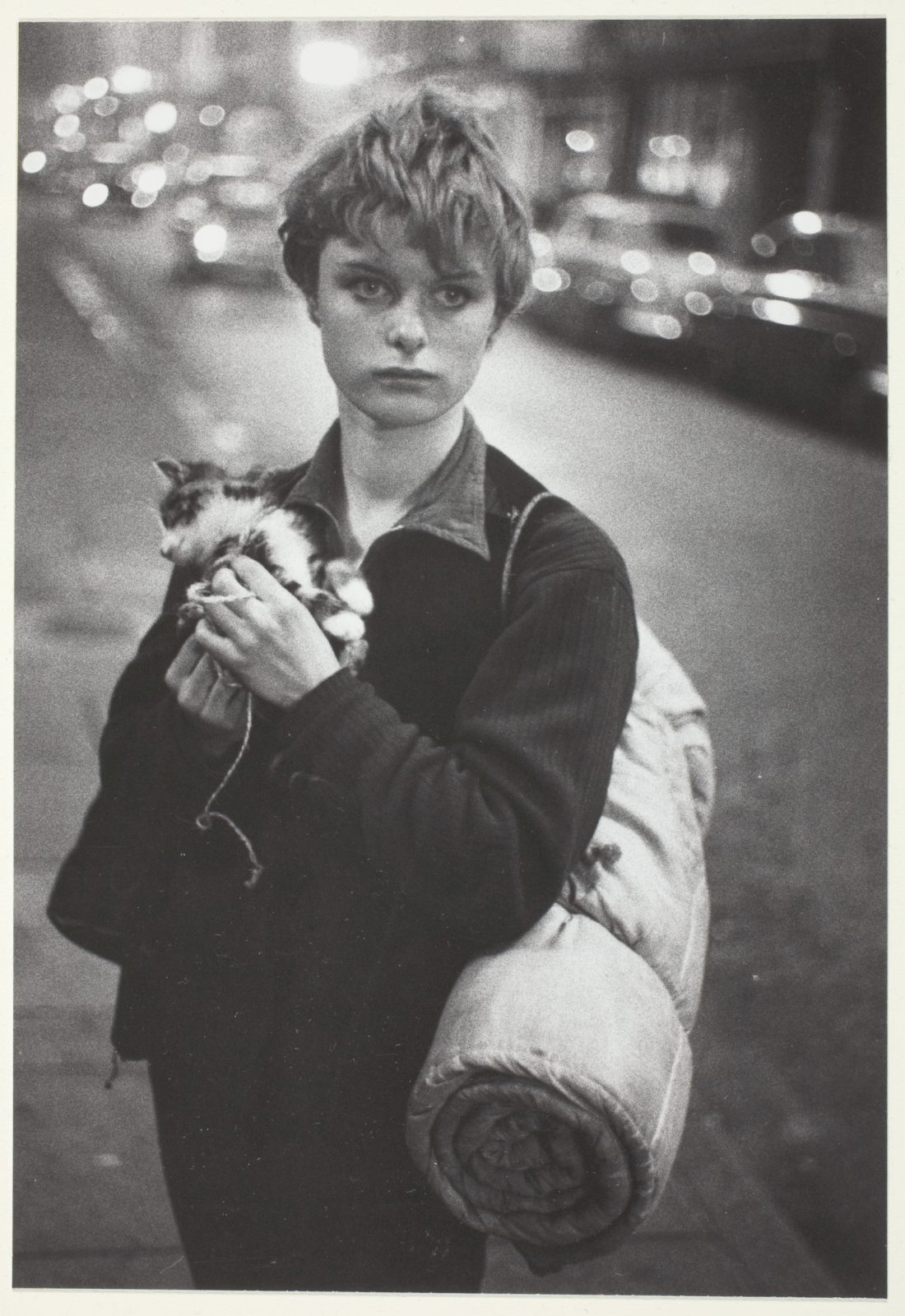

Bruce Davidson, Girl Holding Kitten, 1960. © Magnum Photos, Inc. and Bruce Davidson

Bruce Davidson, Girl Holding Kitten, 1960. © Magnum Photos, Inc. and Bruce Davidson -

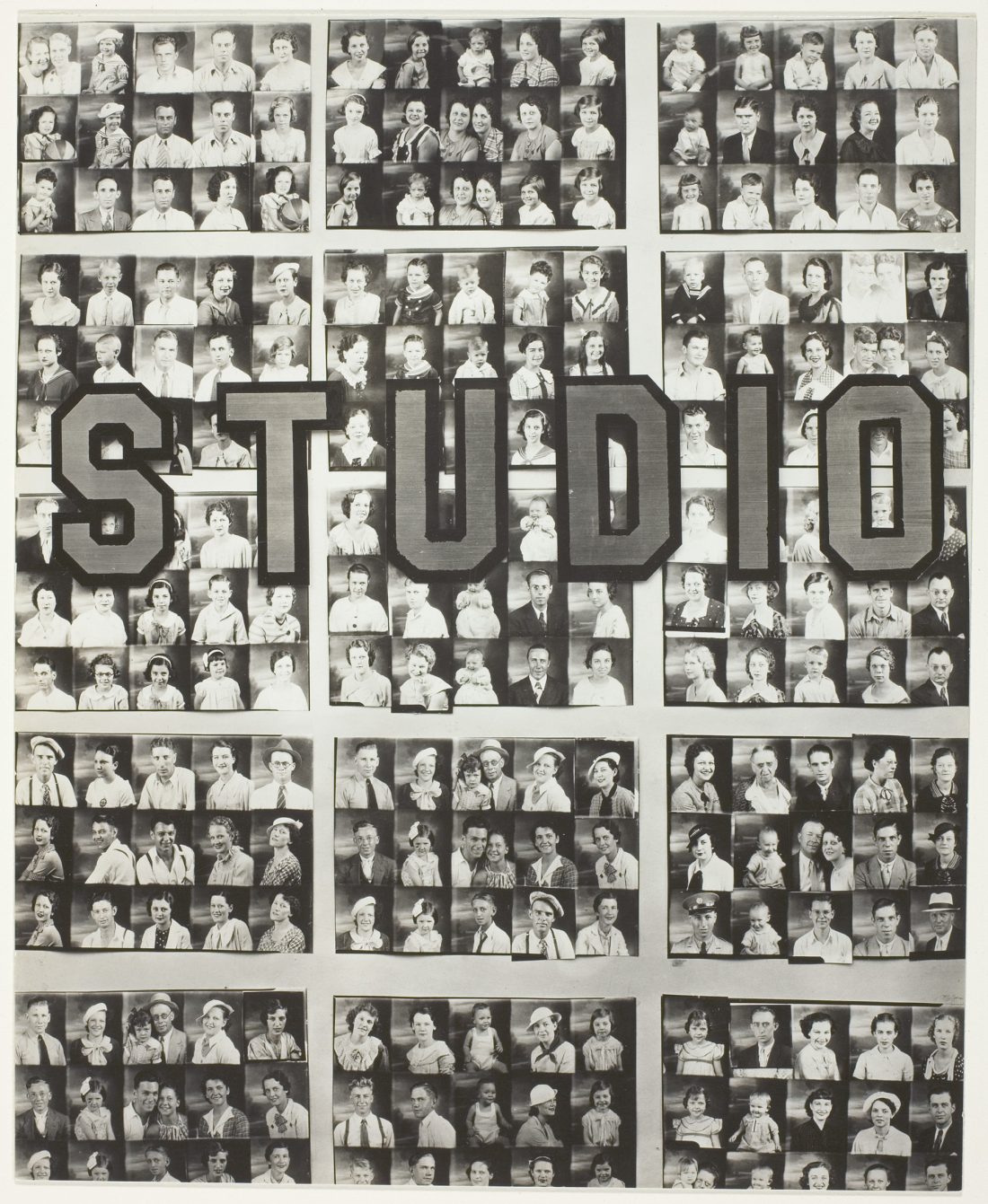

Walker Evans, Penny Picture Display, c. 1962. © Walker Evans Archive, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Walker Evans, Penny Picture Display, c. 1962. © Walker Evans Archive, the Metropolitan Museum of Art -

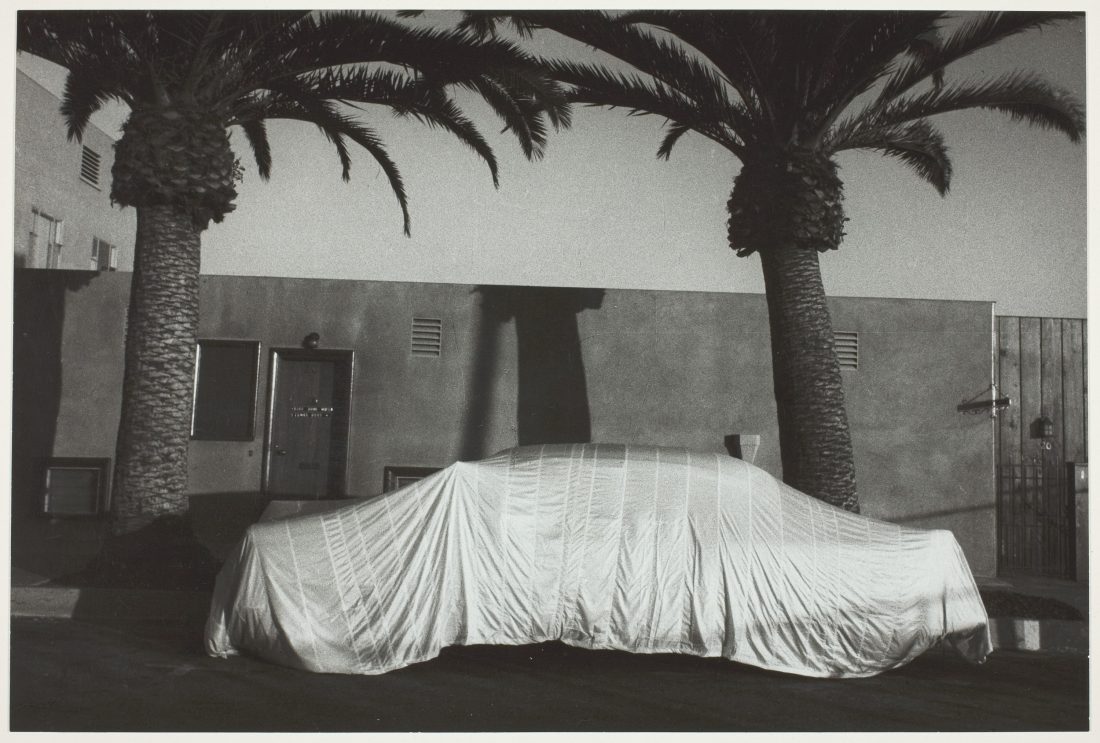

Robert Frank, Covered Car, Long Beach, California, 1955/56. © Robert Frank, from The Americans. Courtesy of Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Robert Frank, Covered Car, Long Beach, California, 1955/56. © Robert Frank, from The Americans. Courtesy of Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York -

Dave Heath, Untitled, 1963. © Estate of Dave Heath

Dave Heath, Untitled, 1963. © Estate of Dave Heath -

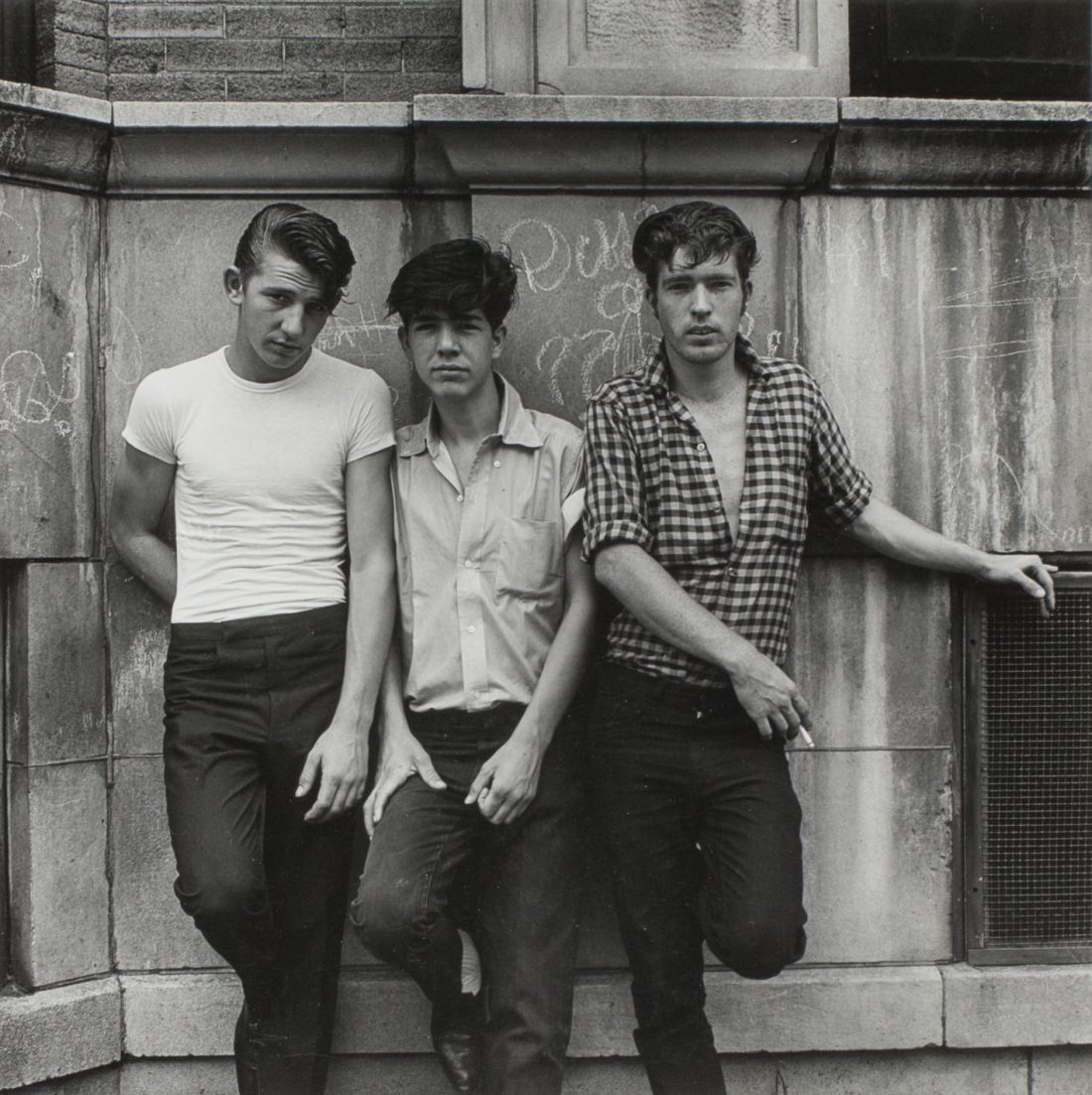

Danny Lyon, Uptown, Chicago, 1965. © Danny Lyon, Courtesy Gavin Brown Enterprises

Danny Lyon, Uptown, Chicago, 1965. © Danny Lyon, Courtesy Gavin Brown Enterprises -

Ray K. Metzker, The Loop: Chicago, 1958. © Estate of Ray K. Metzker

Ray K. Metzker, The Loop: Chicago, 1958. © Estate of Ray K. Metzker -

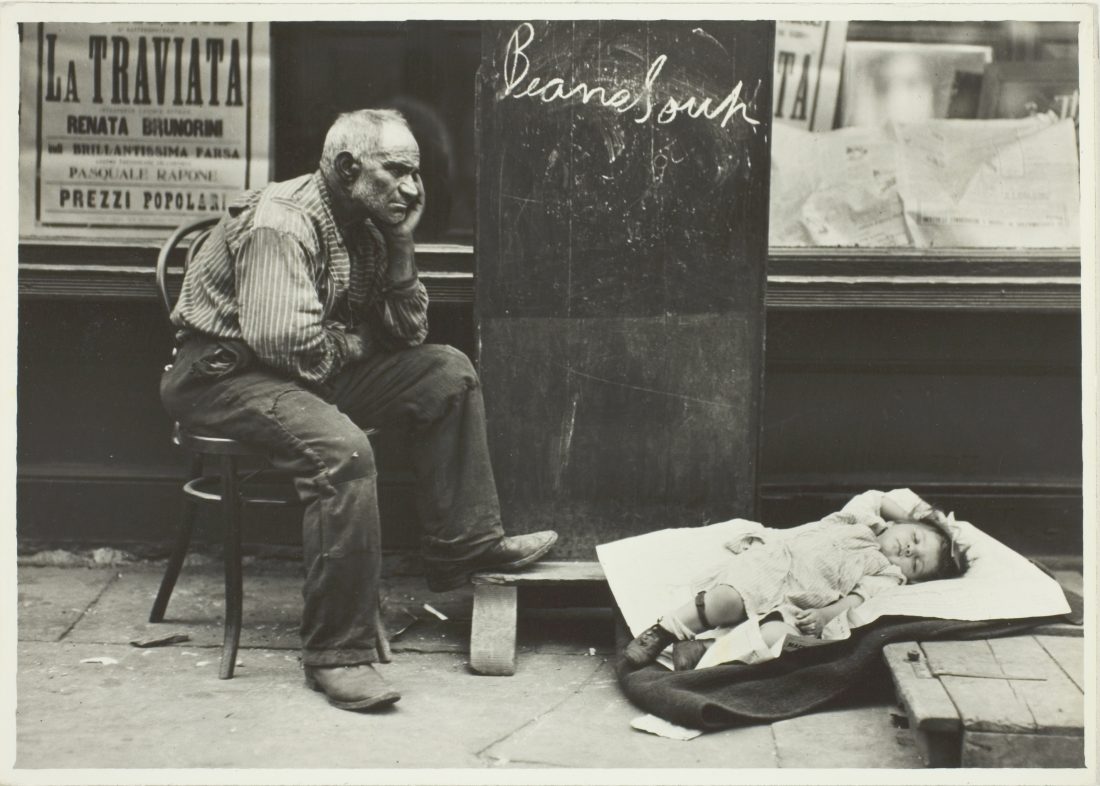

Lewis Wickes Hine, Fresh Air for the Baby, New York East Side, c. 1910

Lewis Wickes Hine, Fresh Air for the Baby, New York East Side, c. 1910

Twenty He Championed

Hugh Edwards played a critical role in the careers of many photographers. From the start of his tenure as the curator of photography at the Art Institute in 1959, he committed to presenting almost solely monographic exhibitions, “to represent an individual’s use of the camera and a summary of his discoveries.”[1] The artists he highlighted ranged from nineteenth-century practitioners to acclaimed modern photographers to young artists fresh out of school. Through this expansive yet rigorous exhibition program—along with select acquisitions of work for the permanent collection—Edwards showed the public artists who defined photography’s history through markedly individual approaches.

At a moment in which American museums paid little attention to the first decades of photography, Edwards sought out work by the medium’s earliest practitioners. In addition to loose prints by Julia Margaret Cameron and Eugène Atget, he also acquired albums of photographs documenting the Civil War by Alexander Gardner, the American West by Timothy O’Sullivan, the Crimean War by Roger Fenton, and the Middle East by Maxime Ducamp and Francis Frith. He made these available to museum visitors in the Print Study Room and, when possible, exhibited them to help instruct photographers and the public alike about artists of the past.

Edwards passionately supported photographers working in what he identified as a twentieth-century American realist tradition; beginning with Lewis Hine and Walker Evans, this approach continued, he believed, in the work of W. Eugene Smith and Robert Frank. He also collected, exhibited, and enthusiastically corresponded with other major figures of twentieth-century photography, including Ansel Adams, Aaron Siskind, Frederick Sommer, Edward and Brett Weston, and Minor White. When he acquired work by these artists, he often tried to obtain a career overview rather than examples from their latest series, although in many cases the exhibitions were focused on recent work.

Edwards arguably had the greatest impact on the careers of emerging contemporary artists. He eagerly sought out new talent in books, magazines, and unconventional exhibition spaces, identifying photographers who depicted the world with empathy and humanism. Giving critical early support, he typically exhibited these makers’ newest photographs, afterwards acquiring a selection for the permanent collection; Edwards also shared his enthusiasm through frequent recommendations in letters to curators, collectors, and other photographers and through the occasional book foreword. He was very supportive of young Magnum photographers, including Bruce Davidson, Sergio Larraín, and Dennis Stock. He showcased artists who worked or studied in Chicago, including Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Rudolph Janu, Algimantas Kezys, and Ray K. Metzker. And he enthusiastically encouraged Dave Heath’s sympathetic scenes, Simpson Kalisher’s photographs of railroad men, Duane Michals’s portraits and images of a lonely New York, and Robert Riger’s dynamic sports photographs, identifying in each a new approach to camera work. In a few instances, Edwards developed lifelong friendships, as with Danny Lyon, for whom he served as a mentor on several projects. Presciently, Edwards also foresaw the importance of young photographers not yet appreciated by others in the field, including Robert Frank. In an inscription in Edwards’s copy of The Americans, Frank succinctly expressed the value of the curator’s support and efforts: “with gratitude and respect to help + encourage when it mattered.”[2]

Frances Dorenbaum, Dangler Curatorial Intern, Department of Photography

[1] Edwards, “Some Experiences with Photography,” Contemporary Photographer 4, 4 (Fall 1963), p. 6.

[2] Robert Frank, handwritten dedication in The Americans (Grossman, 1969), Hugh Edwards Archive, collection of David and Leslie Travis.

Citation: Frances Dorenbaum, “Twenty He Championed,” in Hugh Edwards at the Art Institute of Chicago, 1959–1970 (Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), http://media.artic.edu/edwards/.

Artists